“When you go out to play, you really want to put the audience at ease. You want to make sure that they’re okay. So when you’re, when you kind of reverse it and think, oh my God, they’re all looking at me and what am I going to do? Your goal is to put the audience at ease, have them enjoy. It’s all about the music. It’s all about the play. It’s all about what you’re trying to express. You know, the music. That’s what it’s about.”

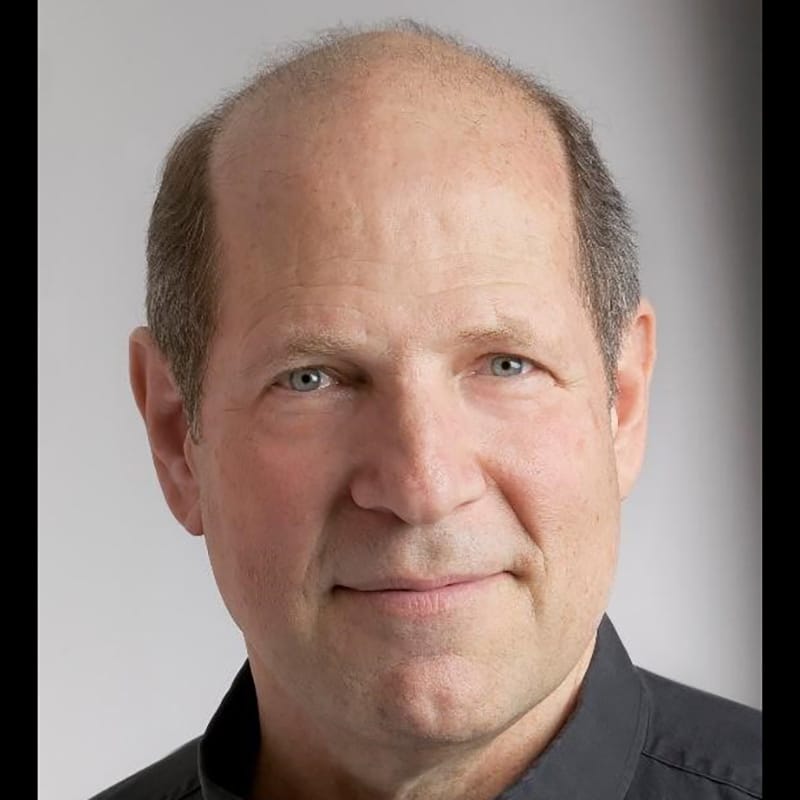

~ David Singer

The highly renowned classical clarinetist, David Singer, has performed many times at Carnegie Hall. He was a principal member and soloist with the Grammy Award-winning Orpheus Chamber Orchestra for 36 years and is featured on many of the group’s 70 CDs on Deutsche Grammophon.

David began with Orpheus when the group was playing for free. He has played with many of the world’s greatest classical musicians, including legends like Yehudi Menuhin, Itzhak Perlman, Rudolf Serkin, and Yo-Yo Ma among others.

David has also performed at the White House with Music from Marlboro and The Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society for Presidents Carter and Clinton.

David’s recently published memoir, From Cab Driver to Carnegie Hall, is more than a musician’s autobiography; its inspiring narrative will resonate with anyone who has faced life’s challenges head-on. It’s an ode to the power of never giving up while giving oneself every chance to succeed.

I’ve read David’s book and found it to be a fascinating, uplifting reflection of a life in music that’s been full of challenges, triumphs, and the transformative power of music. If you enjoy stories about artists succeeding despite difficult obstacles, I highly urge you to read David’s entertaining memoir.

WEBSITES:

David’s site: https://singerclarinet.com/

From Cab Driver to Carnegie Hall

IF YOU LIKE THIS EPISODE, YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY:

- Doug Besterman, Orchestrator-Arranger-Composer—Episode #363

- Qin Sun Stubis, Columnist-Poet-Author—Episode #359

- Marcia Peck, Writer-Musician—Episode #352

- Michael Mason, Musician (Session 3)—Episode #340

- Jon Kremer, Writer—Episode #319

- Michael Mason, Jazz and World Flutist (Session 2)—Episode #276

- Michael McCuistion, Lolita Ritmanis, and Kristopher Carter, Composers—Episode #191

- Corky Hale, Jazz Harpist-Pianist-Singer—Episode #190

Steve Cuden: On today’s Story Beat.

David Singer: When you go out to play, you really want to put the audience at ease. You want to make sure that they’re okay. So when you’re, when you kind of reverse it and think, oh my God, they’re all looking at me and what am I going to do? Your goal is to put the audience at ease, have them enjoy. It’s all about the music. It’s all about the play. It’s all about what you’re trying to express. You know, the music. That’s what it’s about.

Announcer: This is Story Beat with Steve Cuden. A podcast for the creative mind. Storybeat explores how masters of creativity develop and produce brilliant works that people everywhere love and admire. So join us as we discover how talented creators find success in the worlds of imagination and entertainment. Here now is your host, Steve Cuden.

Steve Cuden: Thanks for joining us on Story Beat. We’re coming to you from the Steel City, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My guest today, the highly renowned classical clarinetist David Singer has performed many times at Carnegie Hall. He was a principal member and soloist with the Grammy Award winning Orpheus chamber orchestra for 36 years and is featured on many of the group’s 70 CDs on Deutsche Gramophone. David began with Orpheus when the group was playing for free. He’s played with many of the world’s greatest classical musicians, including legends like Yehudi Menuhin, Itzhak Perlman, Rudolph Serkin, and Yo Yo Ma, among others. David has also performed at the White House with music from Marlboro and the Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society for Presidents Carter and Clinton. David’s recently published memoir, From Cab Driver to Carnegie Hall is more than a musician’s autobiography. Its inspiring narrative will resonate with anyone who’s faced life’s challenges head on. It’s an ode to the power of never giving up while giving oneself every chance to succeed. I’ve read David’s book and found it to be a fascinating, uplifting reflection of a life in music that’s been full of challenges, triumphs, and the transformative power of music. If you enjoy stories about artists succeeding despite difficult obstacles, I highly urge you to read David’s entertaining memoir. So for all those reasons and many more, I’m deeply honored to welcome the exceptional clarinetist David Singer to story be today. David, welcome to the show.

David Singer: Wow, what an introduction. I have something to live up to now.

Steve Cuden: Yeah, well, I think you have already done that and it’s well earned. So let’s go back in time just a little bit. How old were you when you Very first became interested in music.

David Singer: I’ve loved music for a long time, but mostly, back in the, well, late 50s, 60s, I was listening, you know, to Elvis or to country western music. Later in the mid-60s, I was interested. I loved the Beatles. I would say that the most spectacular year that I enjoyed with my family and really has everything to do with how I became interested in music was the year that my dad took a sabbatical. He was a teacher at the local high school, band director. And from 1961, August 1, 1961, August 1, 1962, we went to Europe for a whole year. It was just amazing. We were in New York, we were in Paris, we were in Vienna. And when we got to Vienna, he called up the principal clarinetist of the Vienna Philharmonic, one of the great orchestras. My boy plays the clarinet. Will you teach him? And to my surprise, I couldn’t believe he did that. I just had started the clarinet. Ah. He took me as a student and within a few weeks Professor Yetl invited me to sit with him in the Vienna Philharmonic during opera season. You’re very familiar with Broadway and all of the shows and things. Well, this in terms of opera was the top of the top. I mean, the baseball analogy would have been like being a bat boy with the New York Yankees or Pittsburgh Pirates or whatever. So I’m sitting in this great orchestra and it starts, the show begins. I remember La Boheme or Tosca or any of the. You’re looking up at the costumes, the color, the sets, the lighting and the voices, the music around me having these stories. A young woman and a, young man. They meet and they’re both poor and they’re both cold and they get together and they have this, you know, relationship. I mean, just all these different stories of love, of sometimes lust, I mean to all kinds of things and stories that completely related with, with humanity, with, with, with me even as a, as a 12 year old. And so when I thought that one. Once upon a time, classical music was written by, you know, people hundreds of years ago and had no Europeans. for that matter, being there, the music surrounding me is all in Technicolor. And it was just something that I never forgot.

Steve Cuden: Well, you were seeing the show from a position that the audience never sees. Only the musicians see it from the pit, right?

David Singer: Absolutely.

Steve Cuden: Well, that gives you a perspective that’s truly unique. And at 12, I can imagine that was extremely riveting to you watching it.

David Singer: Absolutely. So that really made me feel like, wow, that’s something all of the feelings, all of the emotions, that’s what I wanted to do. So I wanted to play and express emotions that the composer was expressing. Those dots and dashes on the page mean something. They come to life if you really look into who wrote it, when did they write it, and what it means, and then to express them to an audience that really,

Steve Cuden: It’s all about passion, isn’t it?

David Singer: Yeah, absolutely. For anything but we do. Yeah, it is.

Steve Cuden: Because what you’re doing is. Music is an expression of emotion, as you just alluded to. It’s not just a technical thing.

David Singer: No, absolutely.

Steve Cuden: Did you know at that time, as you were sitting there, that you were likely to be, in music business your whole life?

David Singer: No, I had no. I mean, it was something that attracted me. Baseball. I loved baseball. And then music became the next, real passion. And so I did both for a while. But, baseball didn’t work out because I was being the outfield playing little, league or senior league. And I would used to pray that the ball wouldn’t be hit to me, you know, or I didn’t want to be up with the bases loaded. I wasn’t. You know, I told my dad and he said, no baseball. Nah, not for you.

Steve Cuden: If you’re not interested in the ball coming to you, you have a problem if you want to be in baseball.

David Singer: Right.

Steve Cuden: So now that you’ve published your memoir, I’m curious you. Do you also now think of yourself as a writer?

David Singer: No. I mean, really, honestly, the last English class I took was in high school. I went to the Curtis Institute of Music, which is a. Is a very well known, highly respected school. But really, when I, when you graduate, you have a, you get a piece of paper. At least when I went to school there, they give you a piece of paper that says you can play, you. You can play an instrument. Well, good luck making a living with that. You know, really, it’s just crazy. And so the book resonates with maybe with people who are having a hard time from cab driver to Carnegie Hall. Well, I was in both worlds. I played for the President of the United States and the same day went back to New York to drive my cab.

Steve Cuden: We’re going to talk about that in a bit because, we’re going to cover the book in some depth. I’m just fascinated as people figure out how. How they get to where they eventually get. Because you’re sitting there as a child, you have no idea whether you’re ever going to be playing in front of a crowd or as a professional. That’s not something that’s in your head. You’re just barely trying to figure out how to make the instrument work. So along the way, as you were proceeding, you obviously have written this nice, healthy autobiography. Did you keep a journal along the way? How did you remember all these stories?

David Singer: It’s a good question. Well, at my age 103, I mean, ah, long term memory is easier than what I had for breakfast. You know, it’s just one of those things. No, I kept. You know, I always had a date book every year. You know, I mean, you always have a date book, you always have a schedule. And, I have a stack of date books in my garage. I never threw them away. I also have correspondence from, my parents. I wrote to my parents and they would write me back from, you know, my parents. I grew up in la. I have, cards that I would write when I was any parts of the world or so. And then also, you know, remember certain things. But those, Those are primarily correspondence and my m. Date books.

Steve Cuden: So the date books then triggered memories.

David Singer: Yeah, and it really started out as a kind of a game. You know, I’m sort of supposed to be retired, but I’m still playing concerts and they, people ask me to play and lots of times I do benefits for people. But what did I do in the late 50s? What did I do in the 60s? I would just sort of put down highlights. And again, it’s like a jigsaw puzzle and then starting to kind of fill it in. And they kind of took on a life of its own.

Steve Cuden: I think the listeners should pay attention to what David’s saying because it’s great if you can keep some kind of written memory of what you’re doing, whether it’s a date book or a journal or whatever it might be. That’s very helpful if you’re thinking to yourself, someday I may want to write my story, my autobiography. Why the clarinet? What appealed to you early on and what appeals to you still?

David Singer: I had a crush on a girl. I was on the. I guess it was about the third or fourth grade, and I just would see her from afar. Amerie. Rocky.

Steve Cuden: I see.

David Singer: I remember her name. and she was going to enter a talent show. And so I came back to my house one night and I told my dad, I’d like to enter a talent show. And he says, you know, very. In a very supportive way. You don’t know how to do anything. So he was, you know, as the band director, he’d Bring home instruments and the cello and the trumpet and all this kind of stuff. Nothing worked. But then he brought home the clarinet. So the clarinet was the easiest for me, the most natural. So to answer your question, that’s why I played the clarinet. It just seemed to work. So I learned a song about one minute long and. And, entered the talent show, won, beat her, and she wanted nothing to do with me after that.

Steve Cuden: But you learned you found your great love, which was the clarinet.

David Singer: Well, you know, I didn’t ever think of it that way. But it’s interesting because one of my teachers at Curtis, the principal oboist in the Philadelphia Orchestra, John de Lancie, he told me that in all romantic relationships that you might have, the clarinet will never leave you.

Steve Cuden: So where did you get your training? Was it just at Curtis or was it elsewhere? Did Professor Yetl also train you? How did you get training?

David Singer: When I was 12, I learned, from him. I went back to LA, and then again my dad found out who was the best, some of the best clarinet players in town. Richard Lesser was one who ended up principal, clarinet in Israel, Israel Philharmonic. And then Mitchell Lurie became. He was principal clarinetist in Chicago and then became the principal clarinetist with Walt Disney. So he was on all those cartoons that was, you know, that were always playing. You know, he taught me. And so, I had the best, teachers.

Steve Cuden: Well, LA is filled with phenomenal musicians for the studios. What for you makes a great piece of music great? Why is something. Why is this piece appeal to people more than others? What is it about music that makes people, they like it for one reason or another? Do you know?

David Singer: I think a lot of it is subjective. You know, you could take a look at a painting and, somebody will see something beautiful. Or, you know, there’s a picture of, Edvard Munch, he Munch, however you pronounce it, of a woman screaming on a bridge. So some people would look like this, right? And. And others would say, wow, look at that, you know. But to me it’s interesting because when I took my sabbatical, one of them from, Montclair State University, where I was a professor, I worked with composers at SC actually, and UCLA and a few other places. And I would play music that they had written and they would ask me, so what do you think? And so I told them that the composer, you know, the composer wants to create. They want to create, but you don’t do it in a vacuum. What you write, you have to give us a reason to Want to play your piece? Right? It’s like, you have to write a story that people want to do as a play. I mean, you know, you can be by yourself and everything like that, but. And you want to come up. You know, you think about Beethoven, and he just wrote what he felt. Well, he was a genius. I mean, just incredible genius. Mozart, you know, they didn’t necessarily. Although Mozart was told when he wrote his operas, the first one was not particularly happy. And they said, listen, if you want us to do your opera, it’s got to be more happy, it’s got to be more entertaining. And so he did that. But, I told them, why should I play this piece? Where is the feeling? Where’s the emotion? What are you trying to express? That’s all that’s very important. A composer told me that he wrote his piece because he heard his. His son in the next room playing video games, and he heard the sounds of these video games, and he was, like, so moved that his son was there playing video games. So he was writing boop, boop bop boop boop, bop bop, bop bop bop. You know, like whatever, Pac man or whatever it is, that’s fine, but it doesn’t. It’s not going to inspire me to play the piece. I look for something, maybe a melody that. That’s going to be able to be expressive. Something that, makes me feel something. And it doesn’t have to be beautiful. It can be dissonant, it can be angry, it can be funny. But something move me, make me feel something.

Steve Cuden: Surely you have played some pieces of music hundreds, if not thousands of times, and you’ve done scales? Probably, I’m guessing hundreds, if not tens of thousands of times. do you ever get bored playing any of anything that you’re using to practice?

David Singer: I mean, I play scales a lot, you know, but I do it in different ways. I mean, it’s like a vocabulary, you know, it has to be. You have to have control of your hands, you have to have control of your air. You have to have the feel of 3, 4 registers of sounds, and then you can play whatever. And those are the things that need to be practiced. Kind of oiled like the Tin Man. You have to really be able to be very facile with things. So I really don’t. I have to say, though, the art of. I mean, just writing something is also the book. I have an audiobook version coming out, in the next few months, and, doing it through Amazon, audible acx. I think that’s what they call it. That’s very expressive too. How do you read, you know, your. It’s like a play, I guess, right? It’s my script, and so it can really come to life. It’s like playing, except I don’t have to worry about reeds or my instrument working or not. it’s just your voice, you know. So, it’s very, very enjoyable. So I like doing that.

Steve Cuden: So there’s a warmth and a richness in your sound. When I listen to the recordings of you playing, there’s a kind of a warmth to it, which you do get on certain clarinet. Clarinet players, but not all of them. Sometimes it’s a little sharper.

Steve Cuden: What is it you do? Do you do anything to get that warm, rich tone?

David Singer: I have it in my head, you know, the sound that you have. I think the voice that you have has some kind of relationship to what you already. What you hear. And so my biggest influence still, when I was in Vienna, listening to the beautiful sounds that they make in, Vienna, the clarinets, it’s really the reed and mouthpiece. I don’t play their kind of reed and mouthpiece because I couldn’t. It, didn’t work for me. But that sound is always in my head. And so I always try to, That’s what I hear, and that’s what is pleasing to me. So that’s what I do.

Steve Cuden: Who do you think is the greatest clarinetist of all time?

David Singer: Well, I mean, in terms of certainly popular music. I mean, Benny Goodman. I mean, Benny Goodman. Artie Shaw. Today, there are many who are fantastic. Sabina Meyer plays in Europe a lot. There are many who I admire. And they, again, they’re like singers. They’re playing an instrument. They’re playing the clarinet, but you’re not really aware it’s just a voice. It’s a voice that’s incredibly flexible.

Steve Cuden: How interesting, because as a writer, you’re trying to get to where you’re expressing your voice in writing. And you did that, successfully in your book, but. But that you were writing about yourself. So it would be a little easier, I think, to get to your voice writing about yourself. But if you’re writing fiction or if you’re writing a journalism piece or something like that, it’s a little harder to develop what you call your voice. Correct me if I’m wrong. You get your voice as a clarinetist by practicing a lot so that it becomes second nature.

David Singer: By practicing a lot and by listening, by having the experiences wherever you would find it. I for me was going to the opera in Vienna when I was 20, I went back to Europe. They had this, and they still do have what they call steeplatz, where you stand. And I didn’t have any money. So you get there very early, you pay your $2 or something and you run up the stairs five flights and you’re kind of elbowing people. not really, but I mean, you get to a place where at the very top where they have these metal bars and you are standing behind. You tie your scarf there and that’s where you’re going to be standing. So in that hall, the, the Musikverein. Not the Musikverein, the Staatsoper. That’s where I was 12 years old, sitting in the pit with the Vienna Philharmonic. Then as a 20 year old, I was way at the top, at the cheapest seat, standing for five, six hours, including being, being in line. And then later, just in the last few years, I went with my wife and we sat in the best seats in the house, including, which is not necessarily the best. we sat in the front row, in the middle, right behind the conductor. So I had been from the pit to way at the top, to the boxes or in one concert, we were right in the front of the orchestra. There was the Vienna Philharmonic right there. I could reach out and touch them.

Steve Cuden: You’re in that prime spot right where the conductor is. So you’re getting all the sound focused on you.

David Singer: The sound and their kind of grunts and moans and almost hit with sweat, you know. So it’s kind of neat.

Steve Cuden: All right, so I want to talk a little bit about Orpheus and chamber music. What constitutes a chamber orchestra versus a symphony orchestra?

David Singer: Chamber orchestra, like chamber music. Chamber music is smaller for us. The obvious thing was that we didn’t have a conductor. And so, you know, you had, in the beginning, as you said. My book is about overcoming obstacles. One of the, one of them. We started out playing for free as you, as you, as you noted. And then, we got opportunities to play and very fast we became pretty well known. And I think in the 80s, 90s that was, we were the top chamber orchestra in the world.

Steve Cuden: Well, how did it get formed in the first place? How does that happen? You have no conductor, you’re working for free. Clearly you’re not known to start. How does that happen?

David Singer: What happened was, someone named Julian Pfeiffer, a cellist, was at Juilliard and he had friends who, he liked playing with. And not everyone was, wanted. First of all, to play necessarily in an orchestra, that was the easiest. I mean, certainly not easy to get a job in an orchestra. People wanted musicians, wanted to have another way of being able to make music. So I was part of discussions not in the very beginning. 73 is when it started, probably around 1977. We were still meeting uptown at a restaurant called empire Szechuan on 95th and Broadway. Ah, over cold, noodles. I remember, I remember that stuff. And talking about what kind of orchestra we think we should have. Should we have a big orchestra? But if we have a big orchestra, how are we going to do without a conductor? People are going to be sitting so far away from each other. How do we do that? So also how do we do it? Are there going to be many people who are going to be like soloists, or are we going to have a few or of first, chair people and then the others will be kind of followers? Are we going to do it that way? How does it work? If you have many leaders, can we do it with what they later call a flat management style? Or what are we going to do? So we came to the conclusion, at least in the winds and brass, that everyone should be kind of like a soloist. And although that created problems too, because with most music there’s a first clarinet and a second clarinet, first oboe, second oboe, first horn, second horn. So who’s going to play second? Who’s going to play first? And there’s, you know, sometimes differences of opinion. So a lot of things had to be worked out. We also listened to old recordings. What, what conductors do we really like? And, and what, what kind of style were we going to play? So there was a lot of things going. It could be a play, I guess. I mean it, you know, it’s starting out. So we ended up making many CDs for Deutsche Gramophone, which was at the time the top classical recording, label in the whole world. 77 oh recordings. We were asked while we played in Vietnam and all over the place, anyway, we were asked to perform. There’s a club in New York city, of CEOs of Fortune 500, companies, they’re all CEOs. They wanted us to show them how we make it work. Flat management, where we have X number of rehearsals, three or four rehearsals, and then have to play it in Carnegie Hall. How do you make a world class product in a few rehearsals? So we would have them come to our first rehearsal and it was sort of chaotic and people were disagreeing and no, we should try it. Like, no, we should, you know, conflict resolution and being a good listener. Everyone was experienced at playing chamber music. So chamber music, one to a part, no conductor. So we were all used to playing without a conductor. We also found that it was a good idea to have certain whoever was going to play the lead parts for that particular piece. And it would change all the time. But whoever’s playing principal parts would get together before the orchestra would get together and decide how fast this should go. What kind of feeling are we trying to create or recreate? who’s going to give the cue here, who’s going to give the cue there? You know, that kind of thing. We would sort of make decisions. And then when we brought it to the group, sometimes the, last chair violinist would raise their hand. No, I don’t agree. And we should do, you know. But there was less and less of that as time went on and the corps kind of led the rehearsal. And it would go a little more. It was a little more organized.

Steve Cuden: It’s the ultimate act of collaboration. I can’t imagine anything being more collaborative than a group of people getting together and figuring out how to start a piece on the same moment with no conductor, nobody giving you a downbeat. How would you start a piece? What would happen?

David Singer: It depends on the piece. So I was asked by the Thornton School of Music, at sc. Did you go to sc?

Steve Cuden: I went to SC and ucla.

David Singer: That’s right. Okay. So I was asked to teach, to work with the orchestra of the Thornton School and a, la Orpheus. So in other words, the first concert of the year, the first half of the program, they wanted to do it Orpheus style, without the conductor. So we were playing. They were going to play a Rossini overture, which begins with a snare drum like that, really loud. And so we got to the. You know, everyone’s really good at sc. I mean, they’re really talented, bright, right? And so they’re all ready to play. And of course there’s no conductor. And I’m just sitting there. I say, okay, play. And they didn’t know what to do. They had no idea what to do. So I said, well, who plays first? And they looked, the string players, they didn’t know. I mean, it was. And then the way in the back, the, the, the, the snare drum guy raised his hand. I play, I. I play. And then, So, well, so who do you think should start the piece? Who do you think should give the cue for the first piece, for the first note when it starts and the. And the concert Master says, we’re going to take the first cue, from the way in the back for the snare to play. Yes, he has. In that. This case, it was a male.

Steve Cuden: He.

David Singer: He has the. The solo right from the beginning. So then you hear this. I said, wait a second. What dynamic are you supposed to be playing? And it says, well, double forte, you know, loud. And I said, well. And he says, I’m. I’m scared. I don’t want to play something by myself really loud. So this was. This is how we started. And. Like a conversation sitting at a table. You know, you’re listening to someone. Someone speaks and they. They have something that they did last night or whatever. They. They’re bringing something to the attention, you know, and then. And they’re. Oh, really? What? Then what happened? You know, and then somebody else. Like a play. It’s a play. It’s what it is. And we each have our script. Our part is our script. And. And so it’s. That’s the way we put it. You put a piece together. Who is.

Steve Cuden: So.

David Singer: In romantic music, it could start with the bassoon and cl. It could then go to the flute, oboe. And the strings have not as important a part. Then it can be in the string. So it really moves. The conversation moves all over. And so, you have to know what you’re doing to make it work.

Steve Cuden: Classical music is a conversation within the orchestra, isn’t it?

David Singer: It is a conversation. I try to relate things to students in terms of their lives. So when I was working, I had a class in music appreciation. I would work about. One of. One of the sections of the course was about opera. And I would show them from YouTube sometimes, a piece about Don Giovanni, who thought he was God’s gift to women. I said, any of you women out there know anybody who thinks he’s God’s gift? Everybody raised their hand. And then there was Carmen, who was a very sexy, woman of the street, I guess you’d have to say, who seduces a policeman to get her out of jail, and he runs away with her, and then life doesn’t end up very well. That’s kind of a conversation. I guess I’m trying to think that, maybe, popular music, the Beatles have the most beautiful melodies sometimes, I guess in classical music, it’s definitely kind of a conversation, for sure.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s what I’m saying. The pieces themselves are internally conversations musically. I don’t mean literal words. It’s obviously music, but I think a really great piece of music. It feels like, there’s a conversation going on within the orchestra, and that one piece is responding to the others, et cetera, et cetera. And it gets moved, it gets louder, it gets angrier, it gets softer, it gets sweeter, whatever that might be. And it’s, very much a conversation. so how do you go from being in a chamber orchestra to going into a quartet or a trio, which you’ve done a lot of, too. Or what are those differences?

David Singer: Orpheus was like a chamber music group, a string quartet on steroids, really. I mean, it was, 20 of us playing as if we were four or five. That’s what the way we were trying to make it work. You had to have some ideas, but most important is that you had to be a good listener and be willing to try things that you didn’t necessarily agree with.

Steve Cuden: That’s what makes a great collaboration work, is that you’re willing to listen to what the others are doing. If it’s one other person that you’re collaborating with, or 100 people, if you’re listening to what the other people are saying and in their needs. And you can work your way through it so that it’s cooperative and collaborative. That’s what makes it work, right?

David Singer: Absolutely. Absolutely. now, when you have a conductor, it’s a dictatorship. I guess there are different ways of directing. I guess some directors give the actors more leeway and some maybe less. But generally, it’s all about, you know, you got to follow the conductor. It’s all about, you know, you know, watch me, watch me, you know? And, that’s. That’s what it’s all about. So you’re more passive. Generally. Most of the people in the orchestra are more passive. When you don’t have a conductor, you’re more actively involved. So that’s something that I think is wonderful. I created a program for very young children, which has really saved my life, probably because what I was doing during the day regularly was selling welding rod, climbing fences and running from guard dogs, selling welding rod. So it gave the kids the opportunity to create music. And so that was something that was sort of like chamber music.

Steve Cuden: So that’s clearly in your book. We’ll have a conversation now about, From Cab Driver to Carnegie Hall. tell the listeners a little bit more detail what the thrust of the book is, what From Cab. Ah, Driver to Carnegie hall is about. I know it’s your story, but what makes it unique, do you think?

David Singer: One of the things that I find, that people were kind of surprised about is that I Talk about my failures, I talk about losses, I talk about heartbreak and what I did to overcome some of those disappointments. Being in for me, a kind of a dead end job. How, what did I do? How did I get out of that? You know, how did I, how did I turn my life into what it became? And, you know, winning Grammy awards. I was a full professor at a university. I didn’t get a bachelor’s degree, but I was able because of my, the group that I was in and people that I was playing with and recording with, they wanted me, on their faculty. And so I had tenure at a corner office. I could see New York City from my office like a dream. When I was thinking of my first teaching job, going, catching a bus, 20 degrees, waiting for a bus for an hour on a street corner. When I was like 18, taking a bus, walking literally a mile to the school. Once I got to Cinnaminson, New Jersey and the kids, if they didn’t show up, I didn’t get paid. I got nothing. And so that was my first teaching job to being a tenured full professor and all of this. So it’s, been quite a journey. But I thought it would be helpful for people to learn that especially artist biographies or athletes, they don’t talk about when they lost too much. They just don’t. People, I don’t know, people, on a podcast, they’re not going to talk so much about having to do certain things in their lives that they may not necessarily. Especially at the time, I didn’t want anybody to see me driving a cab. You know, all of that stuff.

Steve Cuden: You needed to earn a living, right?

David Singer: You got to make a living. That’s right, absolutely.

Steve Cuden: Well, you know, I have taught many times that the things that you’re reading in the trade magazines, the trade papers, and things that are industry specific, you’re usually reading about things that have succeeded or are on their way to success, or they have been created even if they fail, ultimately they actually got funded, et cetera, et cetera. You’re reading about the successes. What you’re not reading about are the dozens and dozens and dozens of failures where somebody’s tried to get a play, a movie, a concert, an opera, whatever, on and never got there. You’re not reading about that. You’re only reading about the things that are happening or they have happened.

David Singer: Right, that’s exactly, exactly right. How, how do you recover from something like that? And, and, one of the things was kind of an acronym. the word is score S C O R E. It helps me. It’s a creative visualization, a positive visualization that you do before maybe a job interview, before a speech, before whatever, a concert, a play, whatever you. When you’re going to do something that’s going to be stressful, there are ways to prepare and so score. represents. S has to do with self discipline. do the work. You know, if it’s a. If it’s a part that’s going to be hard to memorize, do the work. You know that that’s very important practice. if you’re going to do an interview, you know, find out about the company, all that kind of stuff. That’s very important. Do the work. Self discipline. But that’s the only physical stuff with this acronym. So C has to do with concentration. Concentrate on sending all negative energy away. I’m having a bad hair day. Whatever it is. I don’t feel great. I’m overweight, whatever. It’s amazing when you really think about negative thoughts, they’re there. And so we recognize them and throw them away because they don’t do you any good. O has to do with optimism. Think of, and this is what you can do before, like, you’re going to sleep. you’re just lying in your bed and you’re thinking a lot. So. Oh, you close your eyes. Oh. Has to do with optimism. Think about when you’ve been successful. Think about what happened, how did you feel? And this is also going to be a success for you. Oh, so that’s, optimism. S C O R. relaxation from fear. Fear won’t help you. In fact, it can hurt you. Fear is, you know, people, before they go out to do something, can be frightened and they have this fear. They can’t explain exactly what it is. I’m going to be failure. no, it’s bad. You want to throw it away because there’s no place for that. So fear, you have to recognize not only will it not help you, it will hurt you. So relaxation from fear. and E, enjoyment. Love what you do. Find something that you really like about whatever it is that you’re doing. You know that whatever it is that you’re presenting, whatever it is that you, that you are, going to talk about. So it relates to everyone with those 5s e o r E that has helped me a lot, attain much more than I ever thought I was going to be able to attain. Playing solo, very difficult for me. Well, I played solo with really great players behind me and, you know, and performed with with some of the greatest musicians. You can almost name anybody who’s gone played in the United States and I probably have played with them and it certainly helped me a lot. So I think it, so that’s something else that I think people can get from the book.

Steve Cuden: So the great mythologist Joseph Campbell used to famously say, follow your bliss and the money will follow.

David Singer: not so much money, but I’m doing fine.

Steve Cuden: You know, but that’s the same concept of, you know, make do something that makes you happy that you want to do, not something that you are told to do or you have to do. It’s something that you are passionate about. Again where there’s that word passion, which is a very important word. You know, you write very personally in the book about your personal experiences in your life and it’s very moving and it’s, it’s you know, harrowing. Some of it’s quite harrowing. Especially as a, as a kid you were in difficult times. You write about your father having suffered PTSD in World War II and that he had rages. And I’m just curious, how did you deal with that in your life? And how do you think that that then motivated you to become the person that you are? How did you handle that?

David Singer: First of all, I drove me to make, to. I couldn’t fail. I had to. I didn’t have a safety net, financially and I didn’t have really a safety net, at least for my parents. Psychologically there was no looking back. And so whatever I did, I had to make sure that I was going to be able to take care of myself. Fear of failure, I mean that’s, I guess that’s common. It’s a great motivator, you know. And how, how do you recover from being, you know, having, experiencing child abuse and that’s, it’s not easy to talk about but that’s just, that was my situation. And, and so with some psychological help and that kind of thing, it, they had their own lives and writing the book also helped me understand that they had their traumas in their lives and growing up. And because I go back in time with, with my dad who lived in Eastern Europe with his parents, but then his dad came to the United States way before he sent for the rest of the family. 1933, which is when Hitler came to power in Germany and it wasn’t long after that where if in the book I have a picture of my extended family with my dad as basically a 10 year old kid With a kind of a hula hoop. It was a strange round thing that I guess one of his toys. He was a stuttering little boy clutching onto his parents skirts. And then 10 years later he was awarded a bronze star at the Battle of the Bulge. He was a fierce warrior and you know, soldier. So he had his demons and my mom had hers. Six months old, they went from Kyiv to they immigrated to the United States, ran into the depression, had no job, had no money. I mean it was just terrible, terrible things. And I don’t know about the abuse maybe that they suffered. So they did the best they could. They did kind of apologize to me for what happened. You know, you, there’s a healing you don’t forget, but it’s you, you can sort of forgive in a way.

Steve Cuden: We are as humans an amalgam of all of our experiences. We are one experience, lead to the next, etc. Etc. And so I, I am curious, as a performer, do you think that there’s something from that, that era of your life that motivates you on stage to perform in a certain way, to be a better musician, to play things a certain way? Do you think that that’s had an impact on you?

David Singer: It’s really interesting question. Well, whatever I was going to do, I wanted to just do very well. And I thought that, I thought it was, there was a, there was an opportunity to make people feel, to help people feel better. Can, you know, so music was something that I could do. So as long as I could really get involved with the music. I did a play, with Stockard Channing. She was, you know, she was, she, you know, she played Roxy in Greece and six, Six Degrees of Separation. she did something, oh, she was in West Wing, she was the wife of the president. We did this play called the lady and the Clarinet. Well, you know, you know which role I played, I was the only one on stage with her. And it went for an hour and a half or something. And the play was interesting. You know, you’d be interested. it was all about the past loves of her life. It was it was about three or four different relationships. And I would play music of the time in the background and they would dance and then they would go through their, their thing that whatever happened with the beauty and the love and then the going away and then arguing and then the man would leave and then she’d come to me. And so there was this communication, there was, there was these, these different things. So it was the End of the play. By the end of the play, I’ve been with her the whole time. She ends up in love with me. So that was. That was kind of interesting. it inspires me to want to help the audience feel something. And so that’s very important to me.

Steve Cuden: Did that help you during those struggling years where you were a welding salesman for a while? You also, as the title of your book says, you were a cab driver in New York, and you went from cab driver to Carnegie hall in the same day, basically. Right?

David Singer: That’s right. That’s exactly right.

Steve Cuden: And so how did you overcome that psychologically to do your best, despite being under, I would call, rather challenging circumstances?

David Singer: I don’t know. I had something inside of me. This just. I just felt like I was destined for something better. Not that there’s anything wrong with driving a cab. I mean, it’s a. It could be a great job.

Steve Cuden: No, not. Of course not. But you didn’t set out to be a cab driver. You set out to play clarinet and play it at a high level. And so being a cab driver is challenging to someone who’s. Whose goal, is to be a clarinetist.

David Singer: I looked at it as an opportunity to make a living and be able to stay in the game. Stay in the game? Sort of. I mean, I wasn’t working very much, in terms of music, but, to be around long enough and then play a recital in the Metropolitan Museum and then got a great New York Times review. And things then took off for me, too. But, yeah, I didn’t look at it as, oh, poor me. I had a family, I had a daughter, and I had to make money. And so, my grandfather, he was a painter. And so he was a really. He was actually a professor. He was a highly learned man in Russia. He told people asked him what he did for a living, and he said, I’m a painter. You know, like he was, you know, Monet or something. I’m a painter. He painted prisons and houses. That’s what he did. And he was okay. I mean, it says that’s what he did, you know, so there’s no time to feel, sorry for yourself. You got to go out there and do it.

Steve Cuden: I think the listeners should really pay attention to that, particularly that you do what you need to do in order to get to where you’re going. And sometimes that means you’re doing something that you really didn’t set out to do. It may not be your passion at all, but you sometimes have to do those things. I Myself have been through long periods of time where I’ve needed to work on other things to pay the bills. And that’s just the way that works. But if you have it in your gut and your soul that you’re going to be in, the business that you want to be in, whatever that is, then you keep doing what you’re practicing to do.

David Singer: One thing that really helped me was, I read a book called what color is your parachute? by Bowles, Richard and Bowles or something, which really was a, series of games that, you would fill out the answers to. And then the book based on your answers would say to you, this is the area that you express the most passion for. And for me, it was music and young people. And so I developed a music program. My daughter was in nursery school at the time. For actively getting the kids actively involved with making up lyrics, to songs, making up dances based on their natural movements, what they like to do. There are things that you can do. It’s not of my creation. It was a guy named Carl ORFF in the 19th century, 1920s, who had this thing called Orff Schulferk. He had a whole program based on giving children the opportunity to become actively involved with music as opposed to being taught another Kumbaya song or whatever. And they’re told how to sing the song, they’re told the lyrics, and they have to just mirror what they’re taught. So this was a different kind of pro. So through that, that enabled me to get out of my welding job and ultimately paved the way for my daughter and me to go back to New York.

Steve Cuden: I think I need to ask you an important question about the, clarinet itself. You talk for quite a bit in the book about reeds. How important are reeds? Why are reeds important? What is it that they do for you? Why do you need them to be a certain way?

David Singer: So the reed, it’s where the sound comes from. It’s really where the sound, the reed vibrating against the mouthpiece is. There has to be a vibration, right? So when we speak or when we sing, we go, oh, if we feel our throat, we feeling our, you know, vocal cords vibrate. There’s a vibration, right? Any string instrument, brass, it’s the lips. So for the clarinet and the oboe and the saxophone and all of that, the reed is vibrating sometimes against. If it’s a double reed, like the oboe and bassoon, they vibrate against each other. For the clarinet, the reed vibrates against the mouthpiece. The tip of the reed vibrates against the mouthpiece. And that’s what makes the sound more of. The reed vibrates and then you have a more deep sound. And that’s what I love so much. If you want to play jazz, you have a very open mouthpiece where you can play with a lot of vibrato and do a lot of glisses and that kind of stuff. But the reed and the mouthpiece, if you have a good read and mouthpiece, you can sound great. Well, at least very, very good on a plastic clarinet. You don’t even need an expensive clarinet, really. If you’re a professional, you want a good clarinet. But the reed in the mouthpiece is what makes the sound.

Steve Cuden: I find that fascinating. I don’t play any instruments and I’m always interested in what, musicians, what they have in their bag of tricks, what they look at, how they think. I think that that’s very interesting, that the reed is more or less everything to make the sound the way it is.

David Singer: Yeah, it is, absolutely.

Steve Cuden: So I have to ask you, you know, the old joke is, right, how do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice. Right? That’s the old joke. And clearly you’ve done that. What is it like to play in Carnegie Hall?

David Singer: Well, you know, the history. I mean, you go backstage before the concert, before your first concert or whatever, and you see Teddy Roosevelt, giving a speech on the stage of Carnegie hall, or, the Beatles performing in Carnegie hall, or Benny Goodman or, you know, the history is there actually in Pittsburgh, you have a Carnegie Hall.

Steve Cuden: We do have. We have. We have two of them actually. But the place where most people would wind up playing, where the symphony plays here, is a Hines Hall. But there are two different Carnegie Halls here in Pittsburgh.

David Singer: We played it at one of them. So anyway, what’s it like to play in this Carnegie Hall? You know, it’s just I can’t get away from the history the stage. You look at the marks on the stage and where did that come from? And so you’re surrounded by, this history. And so I wonder what my sound is going to sound like in Carnegie Hall. There are other stages that I think maybe even be there. Maybe there are greater halls, maybe just the sound Symphony, hall in Boston. You can literally whisper like this. And all, ah, the way back you can hear everything someone says, whispering.

Steve Cuden: But were you intimidated the first time you went to play in Carnegie Hall?

David Singer: A little bit. It was very big and our group was very small. I mean, you know, orchestras of 100, 120 play there, and we were like 20 musicians at first it looked very huge. And so how is this going to work? Will we all have to play louder? Do we have to change the way we play? How’s that going to work? When I played with Menu in Carnegie hall, that was something because we walked. I wasn’t just walking to my seat in the back of a group. I was walking front and center, on the stage. And it was a long walk. It was really a long walk. I mean it’s a like walking across the street from where you live. I mean it’s really long. And so that was weird. That was really. And you want to make sure that, yeah, you’re looking around, but you have to also, you have to make sure that you’re, you know, you’re not going to trip and make a fool of yourself.

Steve Cuden: Well, yeah, you’re standing, you’re walking. That’s what people don’t understand about performers. Just the act of walking can be intimidating because everybody’s looking at you. And we’re not used to having everybody look at us when we walk. But suddenly the focus is on you and then you’re going to play. But that’s a whole other story, because that, that you’ve hopefully practiced your way up to a point where it becomes a second nature thing for you. Just the, that’s what I was curious about. The factor of going into this one of the most famous halls in the world and you know, you’re going to be on stage playing. It’s got to be a little bit, get your attention a little bit.

David Singer: It’s sure, absolutely. It’s intimidating. some of the most tense moments in Orpheus, happened during a dress rehearsal. We used to rehearse in the morning of our concert in Carnegie Hall. So some of the biggest fights in the orchestra about how we were going to play something after our rehearsals. And you know, the last one, no, it’s, I really think it should be like this and whatever. And you know, and then somebody thought, why don’t we have our. Some of the kids were having young children by that time, like toddlers. And so why don’t we bring our children to the hall and they can kind of crawl between the players. And so if somebody gets very upset and they look at this 3 year old looking up at them drooling, you know, it’s a little more context, you know, it’s you know, just so that, that helped a little bit.

Steve Cuden: But it does, it puts everything into a context, doesn’t it? It, because it’s not that, that’s not really what life is all about. It’s not about one thing or the other. It’s about all these things.

David Singer: And while it’s. It’s not life and death. Although for a performer who, in the beginning, people didn’t know us, so it was kind of life and death. But, but you have to kind of, you have to not think of that again. You know, relaxation from fear and all that stuff.

Steve Cuden: It’s, every time you performed there was. If you had screwed up once, that would be forgiven. But if you screwed up twice, three or four times and the orchestra was bad and not together, eventually you wouldn’t be playing together.

David Singer: Right? Well, that’s absolutely true. somebody told me that when you go out to play, you really want to put the audience at ease. You want to make sure that they’re okay. So when you kind of reverse it and think, oh, my God, they’re all looking at me and what am I going to do? No, you, you, you go out and your, your goal is to put the audience at ease, have them enjoy. And also, of course, of course. And that’s what I also learned from Stalker Channing. You. It’s all about the music. It’s all about the play. It’s all about what you’re trying to express. That’s the most important thing. The other stuff is extraneous, what they think of me or what am I going to get a review, I had a fight with my wife or whatever. That’s all finished. Don’t think about that then. But, you know, the music, that’s what it’s about.

Steve Cuden: I think that’s absolutely fabulous. Well, I have been having just an incredibly wonderful conversation with David Singer, not only about his life and career, but about his book, as well. And we’re going to wind the show down a little bit. And I’m wondering, in all of your many years of experiences, can you share with us a story that’s either weird, quirky, offbeat, strange, or maybe just plain funny?

David Singer: This was. This took place in my second year at Curtis. I was having. I just really did not like the city of Philadelphia at the time. I didn’t want to be there. My, My clarinet. I didn’t have any good reads to play. I was practicing. I had my two clarinets out there, and the other clarinet was. Was sort of on a clarinet stand. And I was really wondering, what should I do with my life? Is this really what I want to do? Suddenly, bang, bang, bang at the door. It was the fire marshal, and he said, get out. There’s a fire. Fire. And so I thought about this. I thought about it really hard. And I took my clarinet and I put it, both of them, on the floor of my apartment. And then I ran out, outside, because there was a fire that was starting, and they couldn’t control it right then. And I went to the other side of town, to my friend’s house, just to hang out for a few hours until it was. So I figured, okay, if they burn my clariness or if they’re gone, that’s God saying to me that I should do something else because I couldn’t afford to have, you know, purchased another. Another. so I came back, and I could smell the strain, and I could see the black smoke and broken glass and everything. So I walk up the stairs, to the brownstone, went down the hallway, and I opened the door, and there they were. The clarinets were there. Untouched, unharmed. Nothing. No problem. There was black smoke on every. But they were fine. Nothing wrong. So I kept going.

Steve Cuden: That was the sign that didn’t burn up. So you got to keep going forward.

David Singer: Well, that’s it.

Steve Cuden: All right, so last question for you today. David, you’ve given us massive amounts of advice throughout this whole show. Lots of great stuff to chew on for people that are, musicians or they want to be musicians and so on. I’m just wondering, do you have a single solid piece of advice or a tip that you like to give to those who are starting out in the business? If they come up to you and say, how do I do? How do I get in? What do you tell people?

David Singer: So I used to tell my daughter, if you’re really tired and you’re sleeping and it’s terrible weather outside, what is going to inspire you to get out of bed and get dressed and go to work? What is it going to. What would that do? So in other words, what you’re really passionate about, what you really love, is what you should do do. That’s what you should do. Now, Mark Cuban, very successful businessman, said, no, that’s not. That’s not that completely what. Anything that you do well, you’re gonna like. Anything you. You do well, you’re gonna like. So find something that you. That you think you have an affinity for, that you think you might be good at, that you really love and do that. I mean, you know, so there has to be some kind of a reasoning. I’m not going to. I would like to be a baseball player, but not really. It’s not going to Be good for me. But, you know, if you choose something that you, that you really like, that you think you can be good at, I guess that’s the best advice. Now, if you’re in the business, if you’re doing something, I think that the score, that what I mapped out will really help you live the best life. I also, and I’m not a. Certainly not a fanatic about it, but, I have been helped in times when I really didn’t know what I should be doing with my life, or when I was driving a cab and there was a gun being held to my head, or, just different times when I had this wonderful relationship of years, for years. And, and then we moved to Europe and she became an opera singer, and I wasn’t able to work. What was I supposed to do? So when I come to these crisis moments, I would pray. I mean, I would really, I would just. Not just for myself, but how can I. Well, what can I do to, give something in this world? And what am I supposed to do? Please, you know, help me find what I’m supposed to do. And when I had to fight for custody of my daughter. And I’m not saying that you have to win all the time, and I’m sure God has many more things to do than to listen to me. I don’t know. It is in my life. It has made a difference. It really has.

Steve Cuden: Well, I think that that’s what’s helped you along the road, and I think that that’s great advice for anybody that’s seeking, something to help them find their way. And if that’s what it is, that’s what it is. So I think that’s really excellent advice. And anyone who is trying to get in the business, they might need a little prayer along the way. So, you know, it’s not all about skill. Some of it’s a little bit luck, some of it’s a little bit, you know, perseverance with, you know, allowing others to help you along the way. All those things are part of that process. David Singer, can’t thank you enough for your time, your energy, and your wisdom. And those of you that want to. That want to read about David’s life, two things, you can find it through singerclarinet.com Amazon.com and also the book is called From Cab Driver to Carnegie hall by David Singer. David, I thank you kindly for being on the show with me today.

David Singer: Thank you for having me. It was a pleasure. Thank you.

Steve Cuden: And so we’ve come to the end of today’s Story Beat. If you like this episode, won’t you please take a moment to give us a comment, rating, or review on whatever app or platform you’re listening to? Your support helps us bring more great Story Beat episodes to you. Story Beat is available on all major podcast apps and platforms, including Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, iHeartRadio, TuneIn, and many others. Until next time, I’m Steve Cuden, and may all your stories be unforgettable.

0 Comments