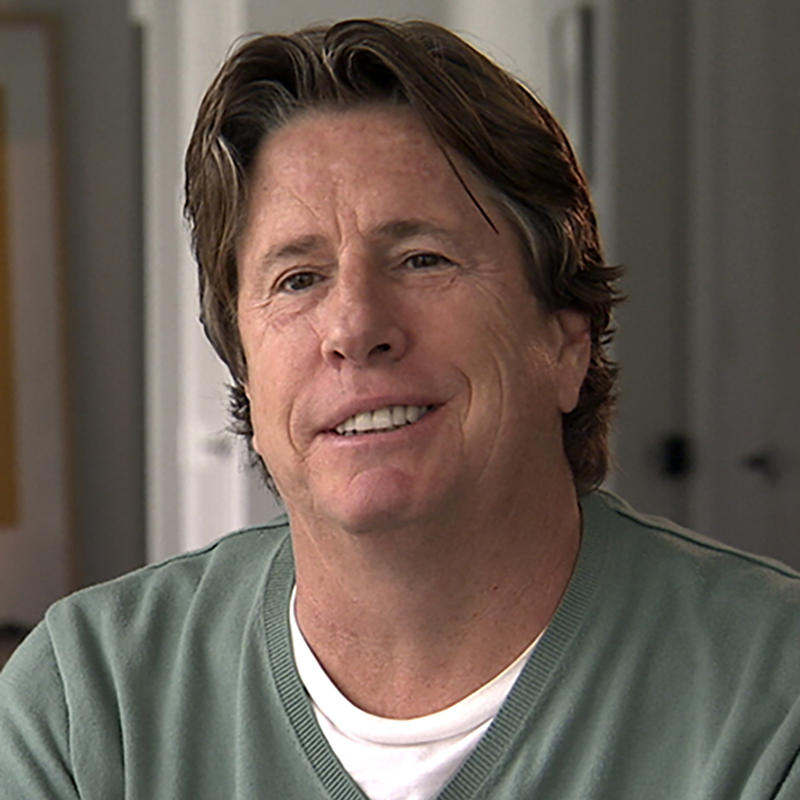

Motion picture writer-director, Andy Tennant, has directed some of the most successful romantic comedy features of all time, including Hitch, starring Will Smith and Kevin James, and Sweet Home Alabama, starring Reese Witherspoon and Josh Lucas.

Prior to that, Andy co-wrote and directed the romantic fable, Ever After, starring Drew Barrymore and Anjelica Huston, and directed the epic drama, Anna and the King, starring Jodie Foster and Chow Yun-Fat.

His last two action comedies, Fool’s Gold, starring Matthew McConaughey and Kate Hudson, which he also co-wrote, and The Bounty Hunter, starring Jennifer Aniston and Gerard Butler, brought his total worldwide box office over the billion-dollar mark.

For the last two years, And’s been directing and producing Chuck Lorre’s hit Netflix comedy, The Kominsky Method, starring Michael Douglas and Alan Arkin.

His latest feature, The Secret, based on Rhonda Byrne’s international best-seller, stars Katie Holmes and Josh Lucas, and will hit theaters in February 2020.

A native of Chicago, Andy studied theatre at USC. Andy’s first job in the movies was as a dancer in the blockbuster musical, Grease, before he eventually went on to direct such hit television shows as The Wonder Years and Sliders.

TRANSCRIPTION AVAILABLE BELOW

WEBSITES:

IF YOU LIKED THIS EPISODE, YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY:

- Hawk Koch, Legendary Movie Producer-Episode #101

- Michael Colleary, Screenwriter-Producer-Episode #109

- Javier Grajeda, Actor-Episode #8

- Todd Robinson

- Byron Werner, Cinematographer-Episode #128

- Nan Bernstein, Motion Picture Producer-Unit Production Manager-Episode #111

- Vincent Jefferds

STORYBEAT WITH STEVE CUDEN

STEVE CUDEN INTERVIEWS FAMED MOVIE SCREENWRITER-DIRECTOR, ANDY TENNANT

ANNOUNCER:

This is StoryBeat, storytellers on storytelling, an exploration into how master storytellers and artists develop and build brilliant stories and works of art that people everywhere love and admire. So, join us as we discover how talented creators of all kinds find success in the worlds of imagination and entertainment. Here now is your host, Steve Cuden.

Steve Cuden:

Thanks for joining us on StoryBeat. We’re coming to you from the Center for Media Innovation on the campus of Point Park University in the heart of downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

My guest today, writer-director Andy Tennant, has directed some of the most successful romantic comedy features of all time, including Hitch starring Will Smith and Kevin James, Sweet Home Alabama starring Reese Witherspoon and Josh Lucas. And prior to that, Andy co-wrote and directed the romantic fable Ever After starring Drew Barrymore and Angelica Houston, and he directed the epic drama Anna and the King starring Jodie Foster and Chow Yun-Fat. His last two action comedies, Fool’s Gold starring Matthew McConaughey and Kate Hudson, which he also co-wrote, and The Bounty Hunter starring Jennifer Aniston and Gerard Butler, brought his total worldwide Box Office over the billion-dollar mark.

For the last two years, Andy’s been directing and producing Chuck Lorre’s hit Netflix comedy, The Kominsky Method, starring Michael Douglas and Alan Arkin. His latest feature, The Secret, based on Rhonda Byrne’s international bestseller, stars Katie Holmes and Josh Lucas, and will hit theaters in February 2020. A native of Chicago, Andy studied theater at USC, where he and I happened to be students at the same time, and we worked together on several shows. Andy’s first job in the movies was as a dancer in the blockbuster musical Grease, before he eventually went on to direct such hit television shows as The Wonder Years and Sliders.

For me, this is a truly great thrill and a deep honor to have as my guest on StoryBeat today, and my friend, the exceptionally talented Andy Tennant. Andy, welcome to the show.

Andy Tennant:

Oh, dear. That’s quite an intro. Thank you for inviting me.

Steve Cuden:

The pleasure’s all mine, believe me. All right. Where did all of this begin for you? We’re going all the way back to when you were a boy. What was the thing or things that led you to pursue life as a performer and then writer and director? What brought you into this?

Andy Tennant:

Well, I think my parents we real moviegoers. They loved movies. I remember my father sitting me down to watch Casablanca when I was probably 12. Seeing moves like Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, it was just a big part of our social fabric. I think when I went to USC, I was interested in film, but it was scary. I loved theater, I loved performing, but I don’t know if you knew this about me, but I was a premed major at USC.

Steve Cuden:

Oh, no. Seriously?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. I didn’t change my major to theater until my junior year, because my parents actually sat me down and they said, “You don’t want to be a veterinarian.” I was like, “But all my friends back in Illinois were either going to be doctors or lawyers.” I think I was a bit embarrassed at the time that I really loved movies and theater. My parents actually are the ones who talked me out of going into med school and following my dream.

Steve Cuden:

That’s the wrong way around, isn’t it? Normally, parents are trying to talk their kids into being doctors and lawyers.

Andy Tennant:

No, exactly. I mean, they did lots of things wrong, but that was the one thing they did right.

Steve Cuden:

Well, they clearly knew something about you that maybe you didn’t even know. Would you say?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. I had no confidence at all in A, my ability or B, my tenacity.

Steve Cuden:

Well, that’s really interesting, because believe it or not, Andy, I remember you as being one of the most confident people I ever knew.

Andy Tennant:

See, I think I’ve fooled a lot of people over the years.

Steve Cuden:

You’ve done a good job at it. Guess what? So have I, so we’re in the same boat. The moving images, the moving part of it, where did you get your training? Obviously, at USC, you were trained in the theater like I was. Where did you learn how to be-

Andy Tennant:

Well, I’m actually very grateful that I have a degree in theater and not cinema, because I think there’s a tendency for cinema graduates, they only think in terms of movie, and they don’t have an underlying understanding and appreciation of what actors do and the material and the written word. I feel like John Blankenchip, who was our professor at SC, taught me more about the human condition than anyone else. I have found, on sets with some of the, frankly, biggest stars in the world, that I actually can talk the talk when it comes to their performance, and I’m not intimidated by talking about acting and performing and subtext and all the things that we learned in the theater that they don’t teach in cinema.

Steve Cuden:

There are very few people I’ve bumped into in life that were like John Blankenchip, that is for sure.

Andy Tennant:

That is true.

Steve Cuden:

He influenced, for better and worse, some of the better performers that have been out there. Yeah. I think that you’re correct that the theater training is probably more important than the cinema training. But where did you learn how to make movies then? Because you didn’t get it while you were in the theater department.

Andy Tennant:

No. I think what happened was, when I was a dancer in Grease, I found myself far more interested in what the crew was doing than what the other dancers and actors were doing, which was waiting around. I found myself really more intrigued and more impressed, I guess, with how things were made. So, I think it was in ’88, there was a writers strike. I had made some money as a screenwriter, and then there was a writers strike, and I decided to take that money and make my own movie, my own short film, and that, to me, was… I went to school on my own nickel and made tremendous mistakes, but also learned as I went, and I made a short film.

Steve Cuden:

You’re expressing street that I’ve heard repeatedly on this show, which is that one of the best ways to make a career happen is to actually do it yourself, to actually do something, not wait around for someone else to give you the chance.

Andy Tennant:

Especially now, with iPhones and the fact that you can make your own film with a… I mean, back in the day, my short film cost $100,000. It was the Heaven’s gate of short films. I would say, now, you can make a film with your phone and edit it on your computer, and it would be better than the film I made.

Steve Cuden:

Well, that’s a matter of taste. But the question is, can you take that and make something good out of it, is the question. And that is the hard part, isn’t it, making something that’s short?

Andy Tennant:

Story, story, story. I mean, it ultimately took me about two years, I was thinking about I wanted to make a short film, what that film would be, and why that was the only film that I could make, and it would be the only project that I truly was the sole author of. Nobody else would be making what I made, and it spoke to me as a writer, as a director, and as what my taste level was, and who I was as a filmmaker.

Steve Cuden:

Was it a comedy?

Andy Tennant:

It was a Mark Twain story. It was called The Cat Story, and it was based on a family story that took place in the ’30s, and it had two 12-year-old boys and cat and old town. It was a comedy. It was very much Mark Twain, and I felt like… I’m from the Midwest, not terribly sophisticated, but I knew this story, and it was funny, and it had an emotional punch at the end. That’s what I made.

Steve Cuden:

And that, then, got you your first directing gig?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah, because what happened was I made the film. Basically, I did everything that I was not supposed to do. It was a period piece, it had kids, and we were working with animals. It was the trifecta of problems. But when it was done, it got screened at Universal, and I got The Wonder Years off of that, because I could work with kids. And I got my first feature writing, directing deal at Universal based on that short film.

Steve Cuden:

Wow. That’s very impressive. And we hear about occasionally somebody even, as you say, with their iPhone movie, somebody that happens for, but it doesn’t happen every day. Now, we’ve got YouTube and all those films are out there, so people can see them quite readily.

Andy Tennant:

And I think some of it, you can get very technical and it can be all cutty and flashy. But at the end of the day, it’s about the story.

Steve Cuden:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). I tell our students all the time, there is no better special effect in movies than a good story.

Andy Tennant:

Well, you’re right about that.

Steve Cuden:

I think so. Obviously, there are some pretty effects out there, but there’s nothing that will appeal to an audience better than story, and we’re going to talk more about that as we get deeper into this conversation.

Steve Cuden:

Let’s go through some of your process. You have been both a writer and a director for this entire time, and you don’t always write what you direct, but I assume that you work on the script as you go, correct?

Andy Tennant:

Actually, I have written with my writing partner sometimes, Rick Parks. We’ve written everything that I’ve made, except for The Bounty Hunter. Even though we haven’t gotten credit, ultimately, my niche in this business was taking a really good idea and a lousy script and rewriting it completely, and then going and getting an actor and making that film. I did it on Ever After, I did it on Hitch, I did it on Sweet Home Alabama, I did it on Fool’s Gold, I did it on Anna.

Steve Cuden:

But it starts with that underlying story that attracted you in the first place, yeah?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah, and a lot of times, you read a script, and it’s really not very good. In fact, Sweet Home Alabama, the original script was unreadable, but it had a great idea. And I think often what happens is you get attracted to not only the idea, but the underlying themes, and it may resonate in your life somehow, and you take that onboard.

Andy Tennant:

When I did Ever After, Ever After was not a very good script. But Rick and I had both just had daughters, and here were these two middle-aged guys being asked to redesign Cinderella for this generation, and we thought, “Well, wait, we just had girls. What kind of story would we want our daughters to see?” And that happened throughout my career on various projects.

Steve Cuden:

Would you say most of your movies have, in some way, been related to your own life’s experiences?

Andy Tennant:

Oh, yeah. I mean, a lot of what I’ve done, it’s semi-autobiographical. Things were going on, I’ve done divorce comedies when I was having trouble in my marriage, giving advice to younger friends of mine who were out in the dating world during Hitch, all of those things. You got to bring something personal to it. I’ve never really made a movie that I don’t have something in it that speaks to me personally.

Steve Cuden:

That’s important to you. I know there are directors that are far more mercenary than that, where they’re just taking a job to take the job. But it has to have some personal connection for you.

Andy Tennant:

Well, for me it does, because it’s a year and a half of my life. I’ve read good scripts, I’ve read bad scripts with good ideas, but a lot of times, you’re… Listen, I don’t have the career where I can just pick and choose anything I want. The things that come to me, unfortunately, now, are romantic comedies, and I feel like I’ve done that. I’ve said all I need to say about certain things. And yet, the movies that I covet and the ones that I haven’t gotten often are movies that I would stretch to do. It’s just the luck of the draw.

Steve Cuden:

All right. Let’s go through what happens once you’ve received a script, whether you think it’s good, bad, or indifferent, and you decide this is something you want to spend a year and a half of your life on. Is the first step to, I assume, aside from somehow optioning it or getting involved in, that you then start to work on the script itself before you go out to an actor, correct? Or are they frequently attached?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. No. Well, it depends. On Hitch, Will Smith came to me after a director that they had, a very talented director, fell out. I got the script and it wasn’t terribly good, but it had a great idea. And I went in to meet with Will, and it was supposed to be a 45-minute meeting, and it ended up being four and a half hours of just debating certain truths about dating and the whole relationships and stuff like that. And then, from there, I got the job, Rick and I did a rewrite, we brought in other writers, I went back to it. They’re all different.

Frankly, I have to audition like anybody else. I get a script, but I’m not the only one who gets a script normally. I’m on the short list of five or 10 other directors, and producer will meet with all those directors and hear what they have to say about the script and how they would fix it or what they would do or how they’d shape it, and they pick the man or woman who probably aligns more with what they think is wrong with the material, and you develop it together.

Steve Cuden:

The very first step, then, is to figure out how to put your slant on it so you can pitch that to a producer.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. It’s really not about figuring it out. It’s just what is my reaction. The thing that you can’t do is go in and brag your way through what you think they want or what you think they want to hear, because ultimately, you have to make that movie, and having been in director jail twice, you’re going to go down with the ship. No one gets blamed except the director.

Steve Cuden:

Explain for the listeners what director jail is.

Andy Tennant:

Director jail is when you make a movie that either doesn’t do well financially or doesn’t do well critically, and you become toxic and no one will hire you, and you end up in director jail for however long-

Steve Cuden:

And you’ve had that twice?

Andy Tennant:

… until you can dig your way out.

Steve Cuden:

Right. Is there a particular thing that you’ve gone through in which you were able to dig your way out and you know that’s a way to do it?

Andy Tennant:

Oh, yeah. No, I went to director jail after Anna and the King, even though it got nominated for a couple Academy Awards and stuff, but it did not do well, and I went to jail. I went to director jail for a couple of years. In fact, I got Sweet Home Alabama after Anna and the King. Sweet Home had been a script that had been around for a long time, and it had come my way after I did Fools Rush In with Matthew Perry and Salma Hayek.

At the time, I read it, I was just like, “This is awful. This is terrible.” And I passed. Two years later, almost three years later, it comes around again, and I don’t have a job, I can’t get a job, and I have little kids. I read it again and I went and had a meeting. In that meeting, they asked me what I would do to fix the script. I said, “Throw it out and start over.” I said that the key for me, which was I think the one signature thing about the movie that makes it hold up even today, is I said, “My wife dated some great guys and I dated some amazing women. I didn’t marry them, but they’re not all idiots, and they’re not all awful people.” I said, “Why don’t we do a romantic triangle where the decision is the choice between the right guy and a great guy?” That, to me, is a photo finish, but it also says that if Reese Witherspoon is going to be engaged to a moron, that makes her an idiot.

Steve Cuden:

Yes, for sure.

Andy Tennant:

And they’re like, “Yeah, you’re right. That’s great, and go do it.” So, Rick and I went off and rewrote the movie, went down to Alabama on a field trip, and rewrote the movie. Ironically, I then had lunch with Reese Witherspoon, which had nothing to do with Sweet Home Alabama. I had done a movie with her when she was 15. I’d done a TV movie with her.

Steve Cuden:

Which one?

Andy Tennant:

It was called… What was it called? Desperate Choices, and it was Reese right after she had done Man in the Moon, and she was 15, and I was engaged, and we had a lovely time, and then she went off to Africa to make a film. We just kept in touch, and she would call me from various sets, and we would check in and things. We were pals, so we would have lunch every maybe six months, every year, year and half, whatever.

We had lunch in West Hollywood. She said, “What are you up to?” I said, “Oh, I just wrote this script called Sweet Home Alabama. It’s never going to get made. What are you up to?” She said, “Oh, I just made a movie nobody’s going to go see.” That movie came out three months later, and it was Legally Blonde. And then, the studio called me, Disney called me and said, “What do you think of Reese Witherspoon? Her movie opened to $20 million.” I said, “I’ve known Reese for 10 years.” The said, “Well, can we make an offer to her?” A half hour later, Reese called and said, “I just got your script, and I’m going to read it right now.” The next day, she signed on.

Steve Cuden:

Wow. It’s interesting-

Andy Tennant:

That got me out of director jail.

Steve Cuden:

Out of jail. It’s interesting how you can go for two years and can’t get anything, and then it happens in a smash like that, just a snap.

Andy Tennant:

Well, yeah. I mean, the script was… We had done well with the script. I come from a small town, Rick comes from a small town. We created the Candice Bergen character. All of it was just really fun. It just turned out really well.

Steve Cuden:

I don’t know that I’ve seen every one of your movies, but I’ve seen most of them, and I can say that one of the hallmarks of your movies is that they’re very well-structured, and they always have heart and passion, and they leave you at the end feeling like you got a really good, satisfying story. That’s the hallmark of your work.

Andy Tennant:

Well, thank you.

Steve Cuden:

You’re welcome. By the way, the story of the good guy and the better guy, that hack writer Leo Tolstoy once famously said that the best stories come from good versus good, and that’s what you had.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. No. That’s exactly right.

Steve Cuden:

And they are, because then the conflict is that much more painful to the audience.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. It’s just not the easy way, and development can be just heartbreaking and frustrating. I think what producers and studios ultimately look for is a strong point of view that can be backed up. That’s why you just can’t fake it. You’ve got to go in. If you don’t like the script, you don’t like the script, and then if you say, “This is why I don’t like the script, but this is what I would do, because I like her or I like him or I love the idea.”

Steve Cuden:

As we’ve already said a million times, it’s all about that story working. Without it, you’re doomed. When you get a script, when you get something like that and it’s not right, is the first thing you tend to think about story or character?

Andy Tennant:

I tend to think about theme.

Steve Cuden:

Theme.

Andy Tennant:

I tend to think of what is it trying to say. That, to me, ultimately is your North Star on every scene in the screenplay. And at the end of the day, when you start cutting scenes because of the budget or because of your scheduling, any number of things, you always have to think about… It could be a great scene, but is it absolutely necessary to tell the story? Sometimes, they’re not. A lot of times, it’s all about just what are you ultimately saying.

Steve Cuden:

And that’s what you work toward as you’re rewriting the script, or writing it from scratch?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. I think so. I mean, I’m not always successful, but I do read. I’m reading a script now that’s for a movie that I’ve read about 40 pages, and I’m just like, “Oh, God.” But I’m going to finish it, because there is something in it that might be something that I’m interested in. I don’t know yet.

Steve Cuden:

It seems like what you’re then particularly good at is figuring out what those themes are when you read a script, and then taking that and transforming it into a story that has all of the elements we talked about, heart and passion and all those things. That clearly has to be one of your talents.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. I think you got to find the beating heart to the story, and I didn’t get this old without living. For me, I’ve got four kids, I’ve got daughters, I’ve got sons. There’s a lot that can be said that doesn’t have to be trivial. It can still be funny and it can still be heartwarming, but I tend to want to make movies that aren’t terribly dark. I mean, I enjoy going to thrillers and all kinds of films, but that’s just not ultimately what people are going to pay me for to make.

Steve Cuden:

No. I would say you’re definitely a lighter touch. You’re certainly not known for dark movies, that’s for sure.

Andy Tennant:

No. I’m not David Fincher, although there are days that I wish I was.

Steve Cuden:

Well, there are days that we all wish we were, but that’s another story.

Andy Tennant:

Yes, it is.

Steve Cuden:

He spent a couple of years here in Pittsburgh, directing and producing Mindhunter. He’s clearly one of the great directors of our time, but he also has a fairly dark reputation as a person that’s all over the film community here. That’s not you. I can’t picture you being a dark person.

Andy Tennant:

No.

Steve Cuden:

No. So, you’re reading scripts and you’re getting them and they’re not good, but maybe there’s something in them. What’s the biggest pet peeve that you have about new screenplays? Is it that they just don’t have a thematic connection all the way through? Is that the typical problem?

Andy Tennant:

Lazy writing. As a writer and a director, I get frustrated and angry at lazy writing, because I sweat. Rick and I, when we’re together, we struggle over every word, every phrase, every piece of dialogue, every description. Where’s this going, what’s the ending? It’s not good enough. Our first draft is probably 12 to 14 drafts.

Steve Cuden:

Yep, I understand.

Andy Tennant:

Our first attempts and our 10th attempts are crap sometimes. I mean, they’re terrible. Or they’re pretentious or they’re not funny or they’re not whatever. That process to me is so frustrating that I can’t wait to get on a set, because writing, to me, is just dreary.

Steve Cuden:

It’s hard.

Andy Tennant:

It’s frustrating. And it’s hard. But then, when it’s done, I actually feel as satisfied as when I finally see one of my movies when all of it’s put together, when everything’s finally done. But the process is the process.

Steve Cuden:

Is that the ultimate best thing in the world, is to finally see the finished product?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. I have a little tradition. When everything’s finally done, and I mean everything, I like to just watch the movie by myself in a screening room. Then, I can say goodbye to it, because after that, it’s no longer mine. It’s another thing. It’s a product, and other people can trash it or love it or not love it or have an opinion about it, and it’s all done.

Andy Tennant:

And usually, it is. It’s about a year and a half of your life, so when you’re finally done, it’s like, “Is this the best I can do? Is this a movie that I’m really proud of?” And then you have the preview process and all of that. It’s a journey.

Steve Cuden:

What’s your favorite thing of all about the whole process? Obviously, you like to see it finished, but the process itself, what is your favorite part of it? Is it being on set and directing? What’s your favorite part?

Andy Tennant:

Well, when I’m writing, I can’t wait to direct. When I’m directing, I can’t wait to edit. And when I’m editing, I can’t wait to write, because I learn so much about writing and story from editing. That’s my circular thing. I love all of it for different reasons. I love the camaraderie and the people that I meet on set. I love the grueling hours, I love location, I love all of that. That beats you up. It feels like it’s 15 rounds.

And then, you get into the cutting room, and I’ve had the same people, my editors and post-production people and composer, they’ve been the same people for 25 years. They’re really good friends, and we have a system, and it becomes six people finishing the movie. That’s six months of your time. And then, you get to go on the stage where you’ve got 45 or 70 different tracks and channels, and the movie comes alive, and then the print is suddenly perfect. Suddenly, it’s a real movie.

Steve Cuden:

Do you frequently have doubts along the way?

Andy Tennant:

Frequently? You mean every-

Steve Cuden:

Every two seconds.

Andy Tennant:

… waking minute of every day?

Steve Cuden:

Yeah. It’s always doubts.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah, I know, of course you do.

Steve Cuden:

And it’s all the way up through really the first public screening, I assume. Then, you either get a sense of you’ve got a problem, or you’ve done your work.

Andy Tennant:

Well, yeah. I mean, some of it, you just know. Some of the previews can be… I mean, I like the preview process, but it’s terribly nerve-racking. When we did Hitch, for some reason, at the end of the shoot period, I thought for sure I had ruined my career and Will Smith’s career.

Steve Cuden:

Really?

Andy Tennant:

There are stories with that movie about writing every day. We had 45 minutes of footage of phone calls and stuff where the editors would call us and say, “Who is Eva talking to?” And we’d say, “We don’t know yet.” We literally had filmed one side of a phone call, and we didn’t know who she was actually having a conversation with. Well, we’ll figure that out later. We had a lot of that kind of stuff going on, and I just didn’t know.:

I literally went off on a sailing trip with a buddy of mine for a week, just thinking, “I’m doomed.” My phone didn’t work and I just was, “Stop the world, I want to get off.” And a week later, I came back to New York, and I checked my phone, and my editor called and said… My two editors, actually, and they said, “You’re not going to believe this, but it’s really good. It’s really funny.” I was like, “No way!”

I went to go see it, and it was really good. Normally, a director’s cut is 10 weeks after the editors’ assembly, and the editors’ cut. You have 10 weeks where you’re left alone, the DGA protects you, nobody can come see it, nobody can take the film away from you, all those things. And you need those weeks. You need 10 weeks.

On Hitch, we were done in four, and we were like, “We can’t be done. This can’t be done.” We went away, I took the whole post-production team to Vegas for the weekend, and then we came back to look at it again, and we were like, “No, we’re done. This is it.” And then I called the head of the studio, Amy Pascal, and I begged her, I’m like, “We’re done. We have to put this in front of an audience. You can’t see this by yourself.” And she graciously allowed us to have a preview of it, and no one had seen the film.

We went to Vegas, outside of Vegas into the suburbs, and we had a screening in a 450-seat AMC movie theater. Will flew in and snuck in, and the place went crazy. I mean, it was crazy. At the end, Amy turned to me and she said, “Don’t touch this film. Box it and ship it. You’re done.” That doesn’t happen often.

Steve Cuden:

No. I assume you didn’t touch it. It went out as is?

Andy Tennant:

No, we changed I think one closeup, and then we were finished.

Steve Cuden:

That’s remarkable. And it was from-

Andy Tennant:

Yeah, it was. It was nuts, because it was the most painful movie I’ve ever made.

Steve Cuden:

Really?

Andy Tennant:

It’s a big, funny comedy, but there was no laughing on set.

Steve Cuden:

Really?

Andy Tennant:

It was brutal.

Steve Cuden:

I don’t know why, but in my head, I would think it would be a blast with Will Smith and Kevin James, but no?

Andy Tennant:

No. Not that they weren’t great. It’s just we were rewriting every day. We were riffing. It just was not the way. When we did Sweet Home Alabama, we shot the script. On Hitch, there was a script, and then we just went off of that script, and sometimes, I would write all day, and we wouldn’t even shoot anything, and I’d have an entire crew in New York City waiting for pages. It was a lot of pressure.

Steve Cuden:

Wow. That’s amazing. I did not know that. When you see the movie-

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. I don’t ever want to do that again.

Steve Cuden:

Yeah. Well, when you see the movie, that doesn’t show at all. You might see it, but I certainly didn’t see it that way. It looked like a romp, it looked like it was a blast to do. But it was hard. That’s going back to the old Edmund Gwenn line, isn’t it? “Dying is easy, but comedy is hard.” And it is hard. I salute you for sticking so long to doing comedies. Even The Kominsky Method is comedy, and you’ve been doing that for a long time.

Andy Tennant:

Well, that’s different. Honestly, Hitch almost killed me, but The Kominsky Method, I have nothing to do with the writing or anything. That’s all Chuck Lorre, and Chuck Lorre is a genius. I mean, I don’t know how he does it, but he’ll write an episode while sitting in the chair, watching me direct episode two, he’s writing episode three in the chair, just while everyone’s around talking and stuff. He’s like, “Yeah, I just finished episode three.” It’s word-perfect. On that set, the words are everything. You cannot change a word.

Steve Cuden:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). It’s more like a play.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. And it works. It works for him, it works for the actors. That’s why he is who he is. Not everybody is Chuck Lorre.

Steve Cuden:

Well, you’ve clearly worked with bunches of Oscar winners in one way, shape, or form, and those two guys are just about as good as it gets.

Andy Tennant:

I’m so lucky. I did a movie that nobody saw, but it starred Shirley MacLaine and Jessica Lange, and then I went from Shirley MacLaine and Jessica Lange to Michael Douglas and Alan Arkin, and it’s just, meaning no disrespect, Old Hollywood. It’s a lost art. These guys, men and women, are just… They are real legends and real movie stars, and they treat people so well, and they’re so kind, and they’re so grateful, and you’re just like, “Wow.”

Steve Cuden:

And you even got Ann-Margret in there, too.

Andy Tennant:

And I got Ann-Margret in there, too. I only got to work with her a couple days, but yeah. I mean, working with Ann-Margret, it was just like, “Holy.”

Steve Cuden:

Do you have to pinch yourself?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. No, it’s pretty cool. I mean, Shirley MacLaine is like my mom now. We see each other every three months. She is just a dream of a human being. And so are Michael and Alan. I don’t get to see them as often, it’s not like I went to the Canary Islands with Alan Arkin and Michael, but I did with Shirley and Jessica Lange.

Steve Cuden:

Oh, wow. Yeah. Okay. Let’s talk about stars for just a moment. I don’t want to dwell on stars, but they’re there, and they make life easier for someone to sell a movie.

Andy Tennant:

They get your movie made.

Steve Cuden:

Yeah, get your movie made. What is it about stars? Can you put a finger on what it is about stars that makes them stars? Is it too individualized?

Andy Tennant:

That’s a good question. For me, what I’ve often said is, stars are like Thoroughbreds. They’re not a farm horse, they’re not like any other animal. They do one thing incredibly well, they do it better than anybody, and when they run their race, they are the most beautiful thing in the world to watch. But off the track, it’s not like their lives are normal or that they are… It’s a different thing. They look like a horse and they act like a horse, but they’re not a horse. They’re a Thoroughbred, and they do one thing really well. And it is amazing. I mean, it is amazing.

When you hang out and you go, “Oh, they’re just…” Reese is so sweet and I see her up at Pain Quotidien, and she’s got her family, my kids went to school with her kids, and it’s all normal. But then you put a camera on her, and she does this thing that very few people can do, and you just watch it. Same thing with Will, same thing with Drew, same thing with Matthew and Kate and Donald Sutherland. I mean, all of them. It’s a gift.

Steve Cuden:

There’s something that’s, of course, the old line Hollywood, they called it the it factor, there’s something it that you can’t put your finger on. I think you’ve just defined it extremely well. They are Thoroughbreds in a race with a bunch of very good horses. Clearly, you need the supporting cast as well and they need to be good as well, but like you say, they’re not stars, they’re not the Thoroughbred.

Andy Tennant:

Well, it depends. I mean, what I would say is, what I was always surprised at as an actor, you walk into the room and we all have strong egos and you’re insecure and stuff. What I didn’t really realize until I became a director is that the people on the other side, the people whose room you’re walking into, are desperate for you to be good. They’re not there to judge you in some way where you’re just like, “Yeah, you’re lousy. Get out.” They want you to be great. They want you to show them how the material is going to work.

Casting becomes a really interesting… You’ve just got to trust it, because oftentimes, you have people come in and what happens is, you begin to doubt the material because it’s not funny or it just sounds awful, and then one person will come in and elevate everything, and suddenly the material works again, and suddenly that is really funny, and this moment is wonderful. It’s pretty simple when someone walks in and is that person.

It’s not that only these 10 people are stars. I think we’ve learned that, also. I’ve known it for a while, but I think you definitely see it when you watch Britain’s Got Talent, or you see Paul Potts or you see Susan Boyle, and you see people who come on and you’re like, “Well, whatever,” and then they open their mouth to sing, and you’re like, “Oh, my God. What a talent.” I think that’s the same thing. There are amazing amounts of talent actors out there that are really good.

Steve Cuden:

For sure. Well, in my day in L.A., which I’m no longer there, obviously, but in my day in L.A., I wrote 90 teleplay episodes, mostly animation, and you work with voiceover actors, which is a whole other breed. They can take your crummy material and just totally elevate it. You’re talking about something at a different level, where it’s not just the voice, obviously. It’s a face, it’s a persona, it’s all of that. What advice would you give to actors that come in to audition? Is there anything that they can do to have a better chance at getting cast?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. As easy as this sounds, it’s the most difficult thing to do, and that’s be yourself. That means don’t wear your insecurity on your sleeve, don’t push it, be a professional. I’m not judging you as a person; I’m just looking for someone to say the lines. You know what I mean? So many people come in and you want to say, “I’m not judging you, the person. This is just a transactional meeting.” Take the personal out of it so you can just be an actor. Be the actor, I’ll be the director. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve cast somebody who they walked in and I thought, “Well, they’re not who I wrote it for,” and then they blow me away with what they’ve done. It’s like, “Yep, that’s the perfect person.”

Steve Cuden:

There’s no way to define that, though, is there? In other words, for an actor, they have to be themselves, and they have to put something on it, although I would assume that most of the time, you’re looking for some kind of uninflected or calm performance of something.

Andy Tennant:

Well, here’s the thing. Casting a movie is like casting a dinner party that lasts six months. I mean, there are talented people and talented actors that I wouldn’t spend lunch with. I would rather have someone who is genuine and kind and is not a diva, and they may not be the most celebrated, incredible actor ever, and I don’t care, because I have to spend six months with them on some island in the middle of the Atlantic. That’s really what it is. It’s not just about the performance; it’s about the energy that you bring to the room. If it’s manic, manic is fine for a couple of hours, but I can’t see you week in and week out, spend 15 hours a day with you, and have you be a pain in the ass at five in the morning.

Steve Cuden:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). Have you had that happen? I’m not asking for names, but did you have that happen?

Andy Tennant:

No, yeah, of course. Of course I have.

Steve Cuden:

When you have an actor on set and they’re just not… For whatever reason, they’ve had a bad night, they just didn’t read the work that you’ve changed. Do you have a technique for getting them to get where you need them to be?

Andy Tennant:

No, because I don’t think there is a technique. The minute you think you have it solved, somebody shows up with some other issue.

Steve Cuden:

So, you just work it?

Andy Tennant:

So many times, the director has to be… I mean, you just don’t know. Are you just the conductor of an orchestra and they all know their parts and they’re all brilliant musicians? Or is it more like you’re the Music Man with a whole bunch of people who just have been handed instruments they don’t know how to play? You don’t know, necessarily, what the issues are and what they’re bringing to the table and how their day was, but you’re there to do a job. Sometimes you’re their best friend, sometimes you’re their stern father, sometimes you’re their lover, sometimes you’re their best girlfriend. I don’t know until you meet somebody, what it is.

People can just be nervous, people can be tired, hungover, newly divorced, in love. Whatever it is, that’s part of the high-wire act, is that you just don’t know, and you rely on the people that are on set, the people who have to deal with performance. You’re dealing with your camera operator, your DP, your script supervisor, your costume designer, your gaffer. Lots and lots of people are there to help make it good. I’ve had difficult people, but I’ve also had just dream people where I’m like, “I don’t even need to be here.”

Steve Cuden:

They just do it.

Andy Tennant:

They just do it.

Steve Cuden:

You’re saying what has long been known, is that great directors really are really great psychologists, that you understand humans and how to work with them when they’re out there.

Andy Tennant:

But I also think there’s this misnomer of directors are manipulative jerks. All those weird… It’s just not true. It’s about being communicative, it’s about communicating an idea. People love Mike Nichols, he loved actors, they talked. That’s why, getting back to the fact I’m glad I was in theater, because there are a lot of people who are very intimidated by actors, because they don’t know how they do it. They don’t know how they get to a place where they can do some of the things that they do in front of total strangers. If you just have a bit of compassion and you have some sense of human nature and intellect and story, and you’ve written the movie and you know what you need, you do what you can to help them.

Steve Cuden:

Well, yeah. Clearly, when you cast great people, a lot of it’s about casting, isn’t it? Just purely getting the right people.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. Once you’ve cast them, once you’ve… Casting is, I don’t know who said it, but somebody said casting is 80% of the job. Once you have those people, they just come on and they do what they do. They made you laugh in the room, and four months later, they walk on set, you’re like, “Oh, hey, all right! I forgot I cast you. Oh, great, you’re here.” And then they do their thing, and they’re hilarious.

Steve Cuden:

Casting is clearly the key. I mean, I’ve always heard that, I’ve always understood it. Again, no names are needed. Have you ever cast someone, got them to set, and they were wrong?

Andy Tennant:

Have I done that, and have they been wrong?

Steve Cuden:

Again, you don’t need to name names.

Andy Tennant:

Yes, I’m sure I have.

Steve Cuden:

And then, do you replace them? Did you replace them?

Andy Tennant:

Sorry?

Steve Cuden:

Did you replace them?

Andy Tennant:

Have I replaced anybody? No, but I was given the opportunity. I basically called the studio on an actor once, and I was like, “I don’t know what’s happened here.” I was like, “You can see the production report, you should see every take, because this clearly is not working.” And they basically said, “You can fire him if you want. We’ll redo it.” I didn’t. I probably should’ve. Actually, in retrospect, I should’ve fired him within the first 10 minutes, because he was rude and insolent and an ass, but I didn’t.

Steve Cuden:

Oh, God. All right. Can you think of a… I’m looking for a way to get out of some issues. You’ve had some massive challenge on a set, and I’m sure you’ve had more than a few, where there was some big challenge, and things just weren’t working right. What did you do to get out of it? What kind of inspirational thing can you tell people that you worked your way out of a big problem?

Andy Tennant:

There are moments, and other directors have shared this with me, and it made me feel better, which was, there are times when you walk on a set and/or you’re rehearsing a scene and your blood runs cold because it’s not working, where you’re like, “Oh, no.” It’s terrifying, because the meter is running. A director lives at the nexus of the fiscal and the creative. You’re responsible for millions and millions of dollars.

In the case of Hitch, it was $80 million. It’s a lot of money and a lot of pressure and a lot of time, and when things don’t go like you thought they would, you can become a deer in the headlights. I learned very early on to say I don’t know. What is the answer? I’m supposed to have all the answers. I learned very quickly to admit when I didn’t know what to do, because the crew know that you don’t know what you’re doing.

What I’ve done is I’ve turned to other creative types. I’ve turned to the script supervisor, I’ve turned to the DP, I’ve turned to the costume designer, I’ve turned to the producers, just, “Here’s the problem, and I don’t know.” I’ve been rescued probably countless times by other creative people. It’s not just about you, it’s not just about the director. It’s about all the other creative people that are on set.

Steve Cuden:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). Well, you’re surrounded-

Andy Tennant:

I’ll take a good idea from anybody.

Steve Cuden:

I think that’s a great hallmark of any great business leader, any leader. It’s not all on you, that you have a team, and why not take advantage of that team, which clearly, you’ve done. That’s good on you that you don’t feel like you have to solve it.

Andy Tennant:

Actually, it makes the crew relax. I’ve heard stories of other sets, other directors, other actors, other stuff, and I’m just like, “Wow. That’s just not me.” My sets, they’re not a party by any stretch, but they’re relaxed and they’re happy. People need to be kind. I have fired people for being rude and being just an ass.

Steve Cuden:

Obviously, the job that you’ve done most of your career is filled with nothing but pressure of one kind or another. Do you have any particular way that you handle pressure? Do you meditate?

Andy Tennant:

Yes.

Steve Cuden:

What is it?

Andy Tennant:

Yes, fine wine.

Steve Cuden:

Do you carry around a bottle on set?

Andy Tennant:

No. I laugh. I tend to work with a lot of the same people. When I did The Secret last fall, or about this time, in New Orleans, I took the production designer and the art director from The Kominsky Method, because we just got on like a house on fire, and I lived with those two women in a big house in the Garden District, and it was just really fun. It was fun to have people to talk to, fun to have friends. We’d have barbecues, we would just put music on. That was at the end of the day. For me, it’s work hard, play hard, and there were times where we’ve just… You got to blow off steam on a Saturday night or whatever.

I had a producer for 13 years named Wink, from England, and she always said to people, “Don’t mistake Andy’s easygoing nature for that he doesn’t expect you to work as hard as he does.” I think, as long as you can maintain a sense of fun, because it is fun, it’s amazing. To be in the movie business is just the best job in the world, and most of the people that have survived and been there for a long time know that, and that’s why, going back to Michael Douglas or Alan Arkin, they’ve done 50, 80 movies. They know. You can’t be a jerk, and you can’t run crazy. You can’t come to set hungover, you got to get your sleep, you got to eat right, you got to take care of yourself.

Steve Cuden:

Did you, early on, have any incidences in your own self that you had to learn that from, where you didn’t treat somebody well and you had a bad lesson? Or did you just always know that?

Andy Tennant:

I once screamed at somebody on the Hitch set when things had gone pear-shaped. I was exhausted, I was writing all the time, I was getting maybe two, three hours of sleep a night. I thought the movie was going completely off the rails, and I ended up yelling at a sound guy. And we were waiting and whatever, and I found out later that his 10-year-old son was on the set that day, and I just was so ashamed of myself that I called him that night to apologize, and then I asked if I could speak to his son, and I apologized to his son. I’ve never forgotten it. That will never, and has never happened again. It was unprofessional. I still feel horrible about it. I mean, we were fine after that. Anyway. I don’t treat people poorly except for that one time. I don’t treat people poorly, and I expect people to behave themselves.

Steve Cuden:

I think that’s grand, and I think that you’ve obviously, being around a long time, you’ve seen some people come in to audition or whatever that you knew, for whatever reason, were not going to work out because they were going to be like that.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. It’s a chemistry test as much as it is a talent audition.

Steve Cuden:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). That’s a very good piece of advice for anybody that goes in to audition, that it’s a chemistry test, and that, in fact, people are looking to see if they want to be with you for any period of time.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah. It is. It’s a dinner party. “Oh, they’re fun. Oh, they’re interesting. Oh, they listen. Oh, they can tell a good story. Oh, they’re present. They’re not grossly insecure or manic.” Those are the things… It’s not necessarily that you’re looking for that kind of thing. I try to create, and my casting director and I try to create a really comfortable, really warm, embracing room for you to come in to. I know you’re nervous, and I try to do everything I can to make you not nervous.

Steve Cuden:

Well, those are your collaborators, because you clearly can’t make a big movie by yourself. Those are your collaborators. I’m always interested in talking to artists who do collaborate about collaboration. Maybe you’ve already said it, but is there anything else that you can lend to the notion of what makes good collaborations work?

Andy Tennant:

I mean, my writing partner Rick Parks and I, we often say that I didn’t write the movie, Rick didn’t write the movie; the third person that we create together wrote the movie. It’s a little bit of that Lennon-McCartney thing. Together, they were The Beatles, but whether you like John Lennon’s stuff or you liked Wings is a whole other thing. I think we balance each other out.

I have that with my composer. Not my composer, but the composer George Fenton has done every movie I’ve done. He’s a dear friend. When it finally gets to George, I don’t give any direction. I trust him that much to just do the thing that he does. What’s amazing is that his instincts always remind me of what I felt when we wrote it, the moment in the scene. It’s a really fascinating relationship, music to cinema. Music to cinema, and obviously the material, the script to cinema, that’s what I love so much about it. There’s so many other creative facets, whether it’s the costume designer, who has thought more about the character than you have, and what they wear and why they wear it and where they shop and what their socioeconomic realities are. All of those kind of things. I find it… It’s like theater. It’s the community that I covet, because they’re all brilliant in their own right, and collectively, we make this film.

Steve Cuden:

There’s something to be said, Andy, for the fact that you and people like Clint Eastwood and so on always are surrounded by the same people movie after movie. I would say that’s a testament to you. There’s something-

Andy Tennant:

Again, it’s a bit of chemistry and a bit of a shorthand, and you already know that you love these people, and that when you go on location, it can be really lonely. You’re away from your family, you’re working crazy hours, there’s an enormous amount of stress. To have these people who have your back and actually love you and you love them, it just creates a safe zone around the process.

Steve Cuden:

When you’re planning a movie, do you know pretty much what you’re going to do throughout the whole thing? Obviously, you didn’t on Hitch, but do you tend to storyboard, or do you know what you’re going to do in advance?

Andy Tennant:

You mean camera-wise?

Steve Cuden:

Yeah, camera-wise. Obviously, you’ve done some kind of location scouting. Do you know what you’re going to do visually day by day, or do you-

Andy Tennant:

No.

Steve Cuden:

No, you go in and wing it?

Andy Tennant:

Well, yeah. I wouldn’t say I wing it. On Fool’s Gold and some other things, when there are action scenes, those are storyboarded, and the reason they’re storyboarded is not because we got to hope the director knows what he’s doing. You storyboard it so that you know what the first unit has to shoot, in terms of time management and money and closures of streets and stunts and everything. Everybody in all the other departments need to know exactly what we’re doing and who’s doing what, where, when, and how.

You have a green screen unit, you have a stunt unit, you have an action unit, you have the first unit, and you just break it down so that it’s financially feasible, and it’s time management. Those scenes, you do storyboard. I don’t storyboard scenes. In fact, and I’ve worked with the same DP often, Andrew Dunn, and I think this comes from my theater training, I like block scenes and put them on their feet and let’s figure out what the scene is before I decide what the shots are.

Oftentimes, once the actors are up and running in a scene and we’ve got things going on and whatever, then I will find myself standing somewhere on the set looking at it from a point of view, and I’ll look over and there’s my DP looking at it from another side. And then we start talking about, “Well, if we do this here and we do this here, we need to get this here, and we can get a second camera in here.” That, to me, is more organic and part of the process, because you learn… It’s always good to have a plan, because it’s easier, once you have a plan, to go into plan B. If you don’t have any idea what you want to do, then you can find yourself getting stitched up. All that really means is that it’s eating time off the clock. Yes, you call audibles all the time, but you do have a game plan.

Steve Cuden:

Is there… I don’t know the best way to say it. Is there something that you know works time and again in terms of shooting a comedy so that you get whatever the punchline is? Is there something that you fall back on every time, or is it always different?

Andy Tennant:

It’s always different.

Steve Cuden:

Always different.

Andy Tennant:

Always different, because the scenes are different. I know, from John Blankenchip, never move on a joke. That’s pretty much…

Steve Cuden:

You’ve just taught me something new. I never heard him say that. Never move on a joke.

Andy Tennant:

Never move on a joke.

Steve Cuden:

He’s still teaching.

Andy Tennant:

Yes.

Steve Cuden:

He was a character, he really was a character.

Andy Tennant:

No, I know, and doors are funny. There’s a couple things like that.

Steve Cuden:

Doors. That’s true, especially if you’re doing farce, that’s really important.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah.

Steve Cuden:

Andy, we’ve been talking for an hour and five minutes. I’ve just been soaking this in. There are two more questions I need to ask you. One is, you’ve spent a long time working with a lot of people. Can you tell us a particular story that’s either weird, quirky, offbeat, oddball, or just plain funny?

Andy Tennant:

Well, I don’t know if it’s funny, but it’s interesting and weird and oddball.

Steve Cuden:

We’ll take it.

Andy Tennant:

When I did Hitch, there is a scene in Hitch that became rather famous, where Will Smith walks Kevin James to the door and teaches him how to walk a girl to the door and kiss her goodnight. There was a whole thing there. That scene, I wrote that day, all day. That scene was originally about three lines long, and then we had a company move to another place in New York, in the city. The scene was basically, he says something about the paper and his picture’s in the paper and, “What is this?” He goes, “It’s a little bit about me being me,” or something. Will has a line, “No, that’s a little bit of you doing something I don’t ever want to see again.” That was the scene. That’s the end of the scene.

And Will, when we got there in the morning, it was some street in the West Village, he goes, “This is a great street. Why are we only shooting four-eighths of a page?” I go, “I don’t know. What do you want to do?” We start talking and Kevin comes and joins the party and we’re looking at the brownstones and we’re like, “This is a great street. We should do something.” And we start riffing on walking a girl to the door, especially if you have to walk up all those stairs. Then, we got to the 90-10, which is something that Will had come up with or had been told once, so we start talking about that. We talk, and then we go, “Okay, let me try and write a scene.” I go up and write a scene while the whole crew is waiting, bring it to Will an hour or so later, and he likes a few of the lines and a few of the things, I go back, I write it again.

Anyway, around four o’clock in the afternoon, we still haven’t shot a word. We finally come out and I show the scene. It’s a five-page scene. Normally, you shoot two or three pages a day. This was five pages. He finally says, “Okay, we’re going to do it, but it’s now four o’clock.” He and Kevin rehearse it and rehearse it, we have three cameras going, and we shoot the scene in two and a half hours. Five pages in two and a half hours. And it ends up being one of the best scenes in the movie, but it was not written.

The other thing that was fun about it is that actual door, we didn’t have permission from the location managers because we weren’t plan to shoot that day, so Will and I walked up to the door of that brownstone and knocked on the door to see if the owners would let us shoot there. And Sarah Jessica Parker opened the door. It was her house.

Steve Cuden:

Oh, my goodness.

Andy Tennant:

She said, “Yeah, sure.” I even talked to Sarah Jessica Parker years and years later, and she goes, “When Matthew and I see that movie and it comes on and our door comes on, we’re like, ‘Oh, remember when…'” They’re very proud of their door.

Steve Cuden:

That’s completely bizarre. So, you walk up with Will Smith. If you walk up to a house with Will Smith and you open the door, the people inside typically would be flipped out, but you walk up and it’s Sarah Jessica Parker.

Andy Tennant:

Not only that, it was Sarah Jessica Parker, and she looked at me after she said hi to Will, she looks at me and she goes, “Wait, I know you.” And I said, “Yes, you and I went out to dinner in Australia 10 years ago.” I literally was in Australia with a buddy of mine, and we apparently ended up checking into the same hotel at the same time, and my friend worked at Fox at the time, and he introduced himself, and she was like, “What are you guys doing?” So, we all went out to dinner in Sydney, Australia. It’s crazy.

Steve Cuden:

That’s a completely crazy story, because how would you ever expect to open the door to someone else who is a celebrity? That’s just not possible.

Andy Tennant:

Yes. No, I guess it happens in New York.

Steve Cuden:

I guess it does. Okay. Last question of the day, Andy. Do you have a solid piece of advice or a really good tip? Not that we haven’t heard tons of them so far, but do you have a solid piece of advice or a tip for someone who’s starting out in the business, or maybe someone who’s in a little bit and trying to get to the next level?

Andy Tennant:

I do. I have a good piece of advice, which I have given several times. My feeling is that, because L.A. is so spread out and it’s very difficult to network, my advice is, I’ve even given this advice to my own daughter, go to Sundance. Go to the Sundance Film Festival, volunteer, and get into one of those programs. I say Sundance because it’s younger than, say, the Toronto Film Festival or any of the other festivals. But at Sundance, when I was just starting out, I went several times.

But the great thing about Sundance is everyone is very welcoming, everybody is having a good time. Movie stars are hanging out, agents are hanging out, other writers are hanging out, wannabe directors are hanging… Everybody is there, all loving film and loving the business. If you go the Sundance for those two weeks and you go to the movies and you have a good time and you meet people, the truth is, you can come back from two weeks in Sundance and have 50 new friends that you never would have met anywhere else. There’s no way you would’ve met them in L.A., and it would’ve taken you three years to meet that many people.

That, to me, is one of the things that really helped. I mean, I met a lot of people up there that were fellow writers and fellow early directors and early producers and young executives, you network at your level and let that level rise. It’s not like someone who’s 19, the classic story of someone who’s just out of college who meets the CEO of 20th Century Fox and suddenly they have a career. It’s that 22-year-old meets another 22-year-old who’s an intern at that studio, who also wants to be a producer, who’s never done anything else, and you guys start to form a friendship and a bond, and you start to work on this together. And 20 years later, they’re running the studio and you have a career.

Steve Cuden:

Mm-hmm. Yeah. It is a business of people who know people, is it not?

Andy Tennant:

Yeah.

Steve Cuden:

It’s not a business of talent; it’s a business of people who know people that want your talent.

Andy Tennant:

Well, but you got to remember, I think this is one of the big mistakes people make, is that it can’t always be that you walk around going, “What can you do for me?” The biggest mistake that people make is that it’s got to be, what are you bringing to the party for them? Oftentimes, it’s not… I met people when I first got my deal at Paramount, the one thing I could do, I was an okay writer, but I could play golf, I could play tennis, I was fun, I knew my wines, and I started socializing with people and had no other agenda than, “Oh, this’ll be fun.” That’s part of it, too. It can’t just be, “Oh, great. I met someone playing tennis, and now I’m going to call them up and weasel my way into a job.” It just doesn’t work that way.

Steve Cuden:

No, it is definitely a business of making those connections between people in a career. Obviously, you did the right things, and I think that’s very valuable advice in terms of going to a film festival like Sundance, or anywhere where you can meet people en masse. It is difficult otherwise.

Andy Tennant:

Yeah, but you also have to have a life. You can’t just be somebody out there, shilling… You got to live your life on the way to wherever it is you’re going.

Steve Cuden:

Well, how else would you learn human behavior if you don’t live your life? Yeah. That is something that you’ve mastered, is the art of human behavior, because that’s what sells. It’s not special effects, as we talked about. It is people in conflict with characters in conflict with other characters, and that you only learn by living your life. That’s truly valuable.

Andy, this has been a great joy for me to spend a little bit of time with you on StoryBeat. I thank you greatly for coming on the show today.

Andy Tennant:

Well, thank you, Steve. It was fun to talk to you.

Steve Cuden:

And so, we’ve come to the end of today’s StoryBeat. If you liked this podcast, please take a moment to give us a comment, rating, or review on whatever app or platform you’re listening to. Your support helps us bring more great episodes to you. This podcast would not have been possible without the generous support of the Center for Media Innovation on the campus of Point Park University. Until next time, I’m Steve Cuden, and may all your stories be unforgettable.

Hey Steve,

Really enjoyed your interview with Andy! Fun hearing Andy’s stories and his warm-hearted, honest in sites to many aspects of his career! Bravo!

Ron, so very glad you gave the show a listen and liked it. It was great fun to interview Andy.