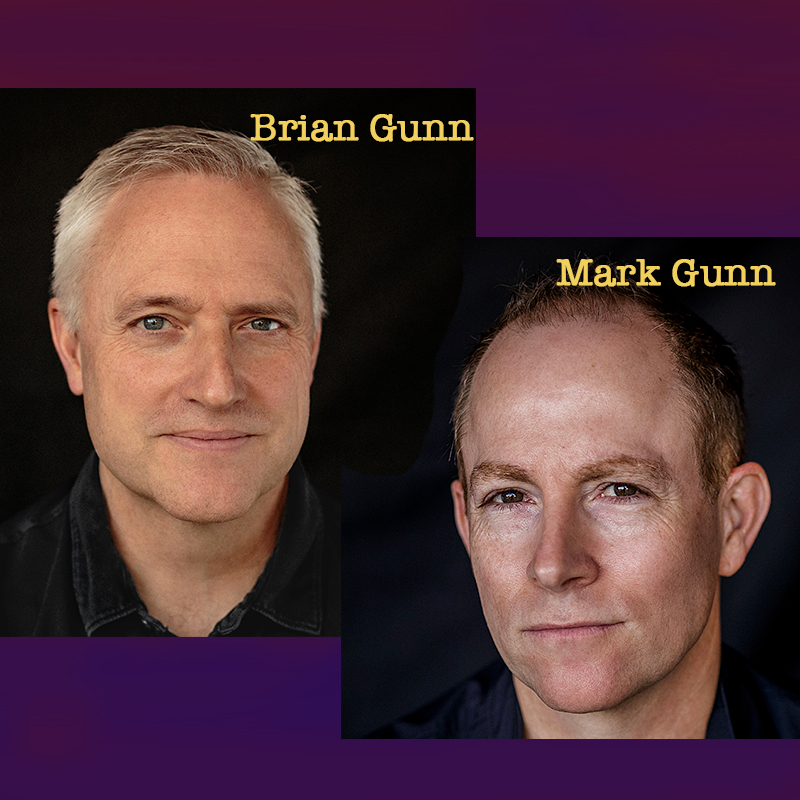

Screenwriters/Producers, Brian Gunn and Mark Gunn, are cousins who grew up in St. Louis, Missouri and attended the same high school and college, where they launched a sketch comedy troupe and began writing together.“Mark Gunn: Writing a competent screenplay is going to bore them. You have to have surprises….You have to try things. You have to take big swings, because competence isn’t enough.

Brian Gunn: The phrase that we probably quote more than any other. This is also by Chris McQuarrie, whose, advice I think is really great.

Mark Gunn: He’s the writer-director of the last few Mission Impossible movies and needed usual suspects.

Brian Gunn: He said, “Why be good when you can be awesome?” We take that to mean there’s all kinds of stuff that we do all the time where it’s like, you know, doesn’t make total sense. I don’t know if we can completely justify it, if it’s the quote unquote correct move here, but it’s so cool and it turns us on, and so we more and more just lean into stuff that we think that provokes a reaction.”

~Brian and Mark Gunn

They moved to Los Angeles and landed their first job by writing the MTV movie 2gether, a spoof about a fictional boy band. It spawned a concert tour, two top-40 albums, and a TV series created and executive produced by the Gunns.

Since that time Brian and Mark have transitioned from TV into film. Journey 2: The Mysterious Island, starring Dwayne Johnson and Michael Caine – a modern-day take on the 19th-century Jules Verne novel – was their first widely released theatrical movie. It was a box-office hit, with global grosses of over $330 million.

Recently, the Gunns wrote and executive produced the superhero horror movie Brightburn, starring Elizabeth Banks, which has become a worldwide success. Brightburn delivers an unusual and unexpectedly eerie twist on the superhero genre.

Brian and Mark are currently working on a film project for Warner Bros to star Jason Momoa and John Cena, as well as writing and developing a TV series for Amazon.

WEBSITES:

BRIAN AND MARK GUN MOVIES:

IF YOU LIKE THIS EPISODE, YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY:

- Greg Weisman, Writer-Producer-Episode #271

- Christopher Hatton, Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #237

- Amanda Raymond, Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #222

- Charlie Peters, Writer-Director-Episode #221

- Karen Leigh Hopkins, Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #207

- Shannon Bradley-Colleary, Novelist and Screenwriter-#182

- Evette Vargas, Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #145

- Vicangelo Bulluck, Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #116

- Michael Colleary, Screenwriter-Producer-Episode #109

- Andy Tennant, Screenwriter-Director, Episode #92

- Todd Robinson, Writer-Director-Episode #89

- Norman Steinberg, Screenwriter-Producer-Director-Episode #27

Steve Cuden: On today’s StoryBeat…

Mark Gunn: writing a competent screenplay is going to bore them. You have to have surprises. You have to. You have to try things. You have to take big swings, because competence isn’t enough.

Brian Gunn: The phrase that we probably quote more than any other. This is also by Chris McQuarrie, whose, advice I think is really great.

Mark Gunn: He’s the writer director of the last few mission impossible movies and needed usual suspects.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. So he said, why be good when you can be awesome? we take that to mean there’s all kinds of stuff that we do all the time where it’s like, you know, doesn’t make total sense. I don’t know if we can completely justify it, if it’s the quote unquote correct move here, but it’s so cool and it turns us on, and so we more and more just lean into stuff that we think that provokes a reaction.

Announcer: This is StoryBeat with Steve Cuden, a podcast for the creative mind. StoryBeat explores how masters of creativity develop and produce brilliant works that people everywhere love and admire. So join us, as we discover how talented creators find success in the worlds of imagination and entertainment. Here now is your host, Steve Cuden.

Steve Cuden: Thanks for joining us on Storybeat. We’re coming to you from the Steel City, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My guests today, Brian Gunn and Mark Gunn, are cousins who grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, and attended the same high school in college, where they launched a sketch comedy troupe and began writing together. They moved to Los Angeles and landed their first job by writing the MTV movie together. A spoof about a fictional boy band, it spawned a concert tour, two top 40 albums, and a tv series created and executive produced by the Gunns. Since that time, Brian and Mark have transitioned from tv into film. Journey Two, the mysterious island, starring Dwayne Johnson and Michael Caine. A modern day take on the 19th century Jules Verne novel was their first widely released theatrical movie. It was a box office hit with global grosses of over $330 million. Recently, the Gunns wrote an executive produced the superhero horror movie Brightburn, starring Elizabeth Banks, which has become a worldwide success. Ive seen Brightburn twice, actually. It delivers one of the most unusual and unexpectedly eerie twists on the superhero genre ive ever seen. If you like superhero and horror movies, I highly recommend it to you. Brian and Mark are currently working on a film project for Warner Bros. To star Jake Momoa and John Cena, as well as writing and developing a tv series for Amazon. So for all those reasons and many more, it’s a great honor and true privilege for me to be joined on Storybeat today by the multi talented Brian Gunn and Mark Gunn. Brian and Mark, welcome to the show.

Mark Gunn: Hey, Steve.

Brian Gunn: Thank you, Steve. We’re happy to be here.

Steve Cuden: Well, I’m so happy to have you here. So let’s go back in time just a little bit. I know you’ve known each other forever, your cousins, and you’re from the same town, in fact. So what was it that first attracted the two of you to the world of writing and producing? How old were you when you started to think about this entertainment industry thing?

Mark Gunn: Well, this is mark. I started doing, both of our dads love movies. I’ve always loved movies, and I think Brian and I love movies since we were little kids. And we both started doing some theater in high school, did some acting in high school, went to the same high school. Many of our family members were also doing theater at our high school. Then we got to college, and as you said in the introduction, we started doing sketch comedy together, and we also did theater there. And at the same time, we were falling even deeper in love with movies. Brian and I had a rule in college that if one of us had a movie, back then, it was vhs tapes a long time ago, had a copy of a movie that neither of us had ever seen, and we brought it to the other one’s dorm room. No matter what time of day or night, we had to watch it. and so we watched a lot of movies in college together, sitting in dorm rooms together, watching college with other friends, too. and it really developed, a real love of movies. And then after college, we, both moved to LA and decided to give it a go.

Steve Cuden: And were you taking classes on how to write and how to be in theater or film? Were those things you studied?

Mark Gunn: No. I mean, no, they didn’t really have those. At our college, we had definitely theater classes. And I was a theater major and an english major, but I acted a lot. For a while, I thought I was going to be an actor. Then I realized I wasn’t a very good actor. So that dream ended. No, it was more the craft of writing was something we sort of learned by doing together. I did go to film school for a year at USC, for grad school, but just for a year. But it’s something that we learned by doing. We learned by doing it together.

Steve Cuden: Same for you, Brian. And you just learned through osmosis of just doing it.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. The first thing that we did together was the, accommodating troupe that, you mentioned. And I think Mark alluded to briefly. I think we did that when I was, We started when I was 19 years old.

Steve Cuden: What was it called?

Brian Gunn: It’s called Epstein’s mother. it’s a reference to, the welcome back cotter character, Juan epstein. He used to always, force signed Epstein’s mother. So that was, the kind of goofball, throwaway pop culture.

Mark Gunn: It was a more timely reference in the early nineties.

Brian Gunn: Exactly.

Steve Cuden: If you say welcome back, kotter to a kid who’s 18 years old today, they just look at you blankly. Like, what?

Mark Gunn: So we avoid saying that because we don’t want the blank looks.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. So, I think that’s where we just, had a very experimental vibe, a very gopher broke vibe. and we got great reactions from it. And that’s where I learned to love writing dialogue. And, this sort of segues into the stuff that we wrote early in the day. We exclusively wrote comedies, early on, together, which was the first tv show that we sold as a comedy. all the movie scripts that we sold were comedies. Every time we, set up a tv series, it was a comedy. And it’s only been over the last, oh, 15 or so years of our career that we sort of expanded out into, more dramatic.

Steve Cuden: Dramatic, for sure. Well, Brightburn is very dramatic. It’s not real funny.

Mark Gunn: That was a movie that we. I mean, maybe we’ll get to this later, but we. We were really only being called about jobs that were comedy or comedy adjacent action comedies, straight comedies. And we wrote that just on our own in our office, on spec, as you know what that means, without, having been hired to write it. Cause we wanted to give it a shot. We had an idea, or Brian had the idea, actually, of what that movie could be. And we wanted to just give horror a shot. And so we wrote that without even telling anyone we were writing it, gave it to our agent and yada, yada, yada. A few years later, it was in theaters.

Steve Cuden: Well, so we’re on it. Let’s talk about Brightburn for a moment. Tell listeners what Brightburn is about. Can you pitch it without giving away the trick to it?

Brian Gunn: It would be hard to, pitch it without giving away the sort of the main. I was going to say gag. I don’t know if that’s the appropriate secret.

Steve Cuden: Secret. The reveal.

Mark Gunn: The idea came from. Brian, came into the office one day and he said, we are. For some reason we were talking about ma and Pa Kent in Superman.

Steve Cuden: Exactly.

Mark Gunn: can’t find a baby in a meteor in their backyard, in this farm, and they decide that they’re going to raise that baby in a meteor as their child. And lo and behold, it turns out to be Superman. It worked out great. And Brian said, a, what kind of parents, what does it take for a parent to think that that’s a good idea?

Brian Gunn: Yeah, you don’t alert the authorities. You don’t, you know, how do you even go about getting a Social Security number? How do you register this child, in school if there’s no birth certificates or anything like that? And I was like, this could have gone sideways a lot of different ways. You know, just like, what kind of people hide that? And, you know, this, this kid could have turned out to be the opposite of superman. You know, this, this kid turned out to be horrible. And, and, you know, thus. Right.

Steve Cuden: That’s the idea. Yes.

Mark Gunn: That was a good, that was a good starting point for a horror movie. That, to us, was always sort of about, we have kids, and it was always about sort of the, some of the horrors of parenting, of, not knowing exactly what your child is going to become, which seems like a fairly universal fear for anyone who’s a parent, is you just don’t. You. You have dreams and hopes and aspirations for your kids when they’re little. And sometimes, though, you, oftentimes they’re not exactly that. Sometimes they’re far from that. Sometimes they are that. But we thought, what is the horror movie version of that, of parenting? And so that was sort of, well.

Steve Cuden: I’ve had the good fortune to actually write for superman and batman. And so you took the tropes, the famous tropes in superman and stood them on their head. And I thought that was really cool. It actually, for a while, it took me a minute to go, wait a minute, this is just taking the tropes and standing it completely on its head, which was great when you finally figured out, oh, wow, this is really unique. Did you get any blowback from the superhero fan community about it?

Mark Gunn: No. There’s always been a, comic books have always had lots of sort of, as, you know, alt variations of telling the main sort of core stories of superheroes. And so there’s a long tradition of versions of Superman and Batman. So I think comic book folks understood that and were cool with it, at least as far as we’ve heard. No one’s been.

Steve Cuden: So nobody rattled your cage and said, hey, what are you doing to my hero? No.

Mark Gunn: Yeah.

Brian Gunn: There have been iterations in the past in comic books of, bad supermans. and, frankly, we were not aware of these when we started working on Brightburn. So there were some people who accused us of, pilfering the idea. we, didn’t, I’ve since gone back, and read some of those sort of evil Superman stories. They’re a lot of fun and a lot of people have done it very well. So I don’t mean to denigrate the people who came before us, but we didn’t get our ideas from them.

Steve Cuden: I don’t think you did because I’ve certainly never seen that take on it, that’s for sure. So you did something very clever, which I recognize you were doing something, I’m going to guess, in a lower budget world was not a giant budget movie. And so you were clever by having a smaller cast with one star, really one big name, and you kept it contained in a sort of a local community, not in a big city. Was that all intentional? Was that something that you contrived while you were writing it?

Mark Gunn: Yes. I mean, we knew that the key to getting, it’s much easier to get a movie made, the lower the budget. And so when we conceived the idea, our first drafts were actually much smaller and more localized than even the movie that ended up.

Steve Cuden: Oh, really?

Mark Gunn: Yeah. We wrote, our first drafts could have been made for, I don’t know, a third of what the movie ended up costing, and it didn’t. And that movie did not cost much money at all. but we knew that that was our goal, was to write something that could get made. And we knew that it was going to be a lot easier to get it made if you could be made for a low price. So that was always part of the plan.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. Like in the movie, the character of Brandon Brightburn, he can fly or at least hover. And, in our initial draft that we sent around town, we thought that even that would be too costly, for indie, production. So he just.

Steve Cuden: So you intentionally set out to write an indie production. You were not trying to go to the big budget world?

Mark Gunn: We were. Not at all. Not at all.

Steve Cuden: I think that was very smart because it got you a movie made, is what it did.

Brian Gunn: Yes, yes, totally. Especially guys like us who don’t come from a horror world. There’s not like people, when they, at least then when they heard our names, would not think horror. So we had a little bit of an uphill climb. but we had this great, director, Dave Yarvesky. and we also teamed up with my brother James Gunn, who’s, a producer and a writer and a director, whom a lot of, your listeners may know, a fairly decent director.

Steve Cuden: I’d say he’s all right. He’s okay.

Brian Gunn: He’s. He’s learning.

Steve Cuden: He’s learning. For those who don’t know, James Gunn directed the Guardians of the Galaxy movies and several others as well.

Brian Gunn: Yes, yes. He now runs the, DC empire right now. So he’s, you know, we’re very close, and I, love him. So obviously I’m kidding when I said that he’s learning.

Steve Cuden: So you left it where there could actually be sequel or sequels. Is there a plan to do more?

Mark Gunn: We’ve talked about it. It’s sort of up to the US and to James and to the studio that we made it with. If we decide that if we have the right idea and everyone’s on board, we would certainly go do it. We’re all sort of busy doing other things, but we’ve talked about it. We’ll see.

Steve Cuden: Well, I, for one, would see it if you brought it out.

Mark Gunn: Thank you.

Steve Cuden: So let’s talk about writing, which is what I’m most interested in here today. Do you think of yourselves primarily as writers or producers or some combo of all that? Do you think that way where you’d present yourself as writers 100%?

Mark Gunn: I mean, I think we’re writers first, foremost. Producers is. It’s interesting because producing, I mean, you know this, but producing in movies and producing in tv are very different things. And in movies, like on that movie, we were executive producers. So producing in movies is a very, very hands on job of hiring crew and staff, and the writers sort of go off and write the script, the director directs it, and the producer sort of oversees the whole thing. But in tv, which we also do, some of the producers are also writers. So, you know, we’re developing a tv show right now, and we will be the executive producers of that tv show, which means that we will oversee all aspects of production. We, will hire the directors, we will hire the actors along with our producing partners. and so in that sense, in the tv world, we consider ourselves very much producers. In the film world, we are very much writers who tend to hand off our projects to other producers to then go make.

Steve Cuden: So then explain for the listeners what the difference is between an executive producer on a movie and a tv show in terms of what the movie executive producer does.

Mark Gunn: That’s a great question. So, ah, in a movie, like, Brian and I were executive producer. An executive producer in a movie, I should say is, tends to be a catch all term for a lot of different contributors to the movie. An executive producer in a movie could have be, could it be the writers of the movie, as we were on Brightburn, who got an executive producer credit? It could be the financier of the movie gets an executive producer credit. It could be someone’s best, friend who they want to give a credit to. So they call him the executive producer. It is, it can be a catch all term, but in tv, the executive producer a lot of times is the person who actually runs the show. usually a writer. Sometimes there are non writing executive producers, but that generally is a term for someone who is actually in charge.

Steve Cuden: And that, I think, is one of the reasons why a lot of the power and control in the, entertainment industry has gone into television. Not so much for writers. That is, not so much in movies, where it’s become more of the director’s medium. And then if they’re a very famous producer, like a Joel Silver or someone like that, or someone from the Marvel Universe or DC Universe gay, become as famous as the writer or more famous than the writer. The two of you have been writing together as collaborators for a long time. Making motion pictures and tv is collaborative all the way through. Anyway. You’re going to collaborate with everyone, actors, directors, producers, designers, editors, etcetera. You’re obviously been doing this a while. What makes a good collaboration work?

Brian Gunn: First of all, you have to just buy into the idea that it’s a collaboration, that you’re not a screenwriter is not a poet or a novelist, where they really get to shape every phase of their own material.

Steve Cuden: Unless you’re Ray Bradbury.

Brian Gunn: Yes, yes, yes. True. And there are, you know, there are obviously, screenwriters out there like Taylor Sheridan or someone like that, who really sort of, own their, you know, my brother James is one of them, you know, where they really, have a. A huge influence on every stage of the process. But most screenwriters are more, they’re cogs. And I don’t say that, disparagingly. It’s. They’re really, like, they have to be able to work with other people. And what that usually means is that you just, you can’t hold on to all your own ideas. You have to be open to the idea that, someone’s going to, come in and, shape it how they see it. Sometimes it makes it worse, in our opinion, when we get notes or we get feedback or we see someone, take, our thoughts and change them in some way or put some spin on it that we didn’t anticipate. And a lot of times it makes it better. And you just have to buy into the whole process, that it’s a group effort, and, you have to be open to the idea that someone’s going to bring something with it that, we couldn’t, see, and that it’s going to make it all better.

Steve Cuden: So writers in movies and tv tend not to own their own work. They lose their copyright to the production or to a studio or a network or whatever. In the theater or in novels, you keep your copyright. That’s a huge difference, is it not?

Mark Gunn: Oh, it’s enormous. And that was something that, our union, the writers guild union, we traded copyright many, many years ago for, and that we get residuals now, but we do not own our material once we sell it. we are then hired to work on our own material.

Brian Gunn: Yeah, it’s almost like you lease your own material. someone’s leasing our material back to.

Steve Cuden: Us somehow, which then gives the production the right to kind of do with it as they wish as opposed to following it.

Mark Gunn: Absolutely. There was a point where we sold Brightburn, for example, which was 100% our idea. And if that studio that bought it wanted to, it could have just cut us out of the process and done whatever they wanted with it. Sure. fortunately, but that happens to writers all the time, and you just have to be okay with that.

Steve Cuden: How long do you think you two wrote together as collaborators before you thought to yourself, you know what? We are pretty good at this. We can make a go at this professionally. How long did it take you?

Mark Gunn: I’m still concerned about that, Steve.

Steve Cuden: You know what? Me too. For myself.

Mark Gunn: I would say we, when we sold that first tv show called together to MTV, and we wrote a first draft that we turned in, and at that time, we had written a movie together, but it was just like a goof off movie. We made a short film together, but it’s just like we were just having fun. And then we wrote first professional script together. I remember turning it in and getting really solid feedback from, the producers, and I thought, okay, I think we can do this now. And I. I shortly thereafter quit my day job, and we made a run at it.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. When we sold together, which became MTV’s first original movie, and then they turned it into a tv series. And so our first real job in this business was executive producer, which is not common. And we realize, I mean, we knew we were lucky then. But even looking back on it, I realized more m and more how lucky we were to just skip over the, all the phases that most writers go through of being you, know, you might be a writer’s assistant and work your way up to being a, low level staff writer and all the way on up the ladder, and you usually have to really pay your dues and work your way up to the bushes. And, we just, sidestep all that, and, we’re suddenly running our own show, and it was, you know, frankly, I don’t know if we totally knew what we were doing. we made a lot of mistakes, but we also got a lot of things right. we found our way.

Steve Cuden: Do you think that the studio, network, whoever, had more confidence in you because you were a duo, a partnership versus a solo act?

Mark Gunn: I don’t know. That’s a good question. It’s possible. I remember when we sold the movie script, and then turned it in, and they really liked it, and they went off. They made it basically without our involvement. They made the movie together without our involvement. And then when the movie was finished, the head of MTV called us and said, I want to turn this into a tv series, and it’s your guys show. You guys can do it. And I think that was because he knew that the voice of that material, which is what I think people responded to, was, came from us initially. And so that’s why it was more that we were the creators of those characters, the creator of that tone. And so I think that’s why they had faith in us to go and turn it into a tv series.

Steve Cuden: It’s an interesting question that you’ve just raised for me, which is, I’ve been teaching screenwriters for many years now, and one of the more difficult things for a screenwriter, or I think any writer, truthfully, to get to, is what you just labeled your own voice. And I think finding your voice is a very big challenge for most writers, and you might write for years before you ever actually develop what is actually your voice. How long did it take, the two of you combined, to find that voice?

Mark Gunn: I mean, I, would say we had a pretty solid voice when we did that movie. And then, especially over the course of two seasons of that tv show, we were pretty comfortable with. But it changes all the time. That voice isn’t, isn’t a static thing. Our voice changes because we change. It changes because the projects we work on change. And so it’s always evolving and changing. And frankly, each project sort of requires its own distinctive voice. It’s always going to be rooted in something that it’s going to be rooted in us if we’re the writers, but that we have to sometimes develop different voices for different projects. The voice in Brightburn is very different than the voice in our MTV show.

Steve Cuden: Very different. I imagine it would have to be.

Brian Gunn: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: that’d be two totally different things. But did that develop between the two of you as you did the comedy troupe early on? Is that where it triggered, or did it happen even before then, as cousins?

Mark Gunn: I would say, probably making jokes together in college is where that started. Is hanging out together in college and just cracking each other up, and our group of friends and stuff cracking each other up. That’s probably where that really started, having the same sort of sense of humor.

Steve Cuden: I ask so that the listener will understand that you have to do what you’re talking about. You’ve got to develop that voice through some activity, whether it’s stand up comedy or comedy sketch troupe, or whether you’re writing, writing, writing, and you’re finding your voice. But the development of a voice as a writer is not something that’s necessarily given to you at birth. You have to find your way to it, I think, most of the time. What, for the two of you makes a good story good? Why do you want to tell a story versus some other story you don’t want to tell? What makes it good?

Brian Gunn: That’s, interesting. I mean, I was thinking about this a moment ago when you were talking about, where did our voice come from? And Mark said that it grew out of just, telling jokes, together. And I remember I heard Chris McQuarrie say once, that if, you can tell a joke, you can tell a story. And, because a joke works very similar to how a story works, you sort of. You build up anticipation, you withhold some information, you’ve got, a payoff that sometimes feels, you know, either very funny or cathartic or a relief. and I think all those things are what make a good. I think people know what makes a good story just from the stories that they’re drawn to. and it’s, you know, you start with a, character, a situation that sucks you in, that you feel invested in you somehow. You might not root for the main character, but, you want to know more. And, that process of a story constantly, you know, leading you along and feeling like, I want to know more. I want to see what happens to this person. I want to see how this ends, the tension that comes from that and the obstacles they face, and then getting that payoff, at the end of a good story. I think it’s very similar to, again, telling a joke, or telling a good story just with your friends or family.

Steve Cuden: so if I’m hearing you right, you’re saying that the key then, for you about good story or good storytelling is that it has to build to a really strong payoff. Is that accurate?

Brian Gunn: Yes. I would think the third act, the climax, the way in which the story resolves itself, I think that all the seeds that you plant early on, that you’re setting up in your story, they all have to build to something that has a payoff. I think that sounds right.

Steve Cuden: So then how do you begin your process? You have an idea. You come up with some story idea from wherever it comes from. I assume that you’re open to all sorts of different areas. Clearly you were in comedy, then you write horror and so on. So you’re open to different genres and ideas. And once you’ve set, upon an idea, where do you then begin? Is it plotting? Is it character? Where do you start?

Brian Gunn: We usually just, when we have a good idea, whether it’s our own or someone else’s idea that we get hired for, we, or even, obviously, before you even get hired, you need to sort of start to. To build out your idea, just to even get the job. we usually just spend time, just what we call blue skying it. And, that means we, you know, we keep pretty much bankers hours here in this, office that we’re in right now, pretty much like nine to five. And, and we, we meet every day. And we meet, we talk in person. You know, we know several writing teams where they trade the scripts back and forth remotely. some of them even are, you know, bipostal writing teams, things like that. They hardly ever see each other in person, but, we like to get together in person. And, then it’s like a very kinetic thing. We’re pacing around the room, and we’re just daydreaming about where it could go and what it could be. and, at that point, we’re not writing any dialogue. We’re not really committing to anything. We’re just jotting down a lot of stuff. And once you have all these sort of like, car parts lying around the garage floor, then you start to put the engine together. And that’s where we like to outline scene by scene to know where we’re headed, again, very different from a lot of, writers and writing teams. a lot of, other writers will just. They’ll just start writing scene one and scene two. And they don’t know exactly where it’s headed. And they just. They just sort of, freestyle it. and that really works for a lot of writers. And, it seems a little too terrifying for us. We like to have, you know, we like to have a little bit of a roadmap. But we usually get down every scene and at the end of it we’ll usually have a nice long outline that’s, you know, 20 pages or so or something like that. And then we go. And that’s when we start writing dialogue scene by scene.

Steve Cuden: I come from the world of tv, and tv is all about outlining.

Brian Gunn: Yes, for sure. Yeah, definitely. Because usually in tv there’s. You’re working with more people and everything has to be approved a little differently and so on.

Steve Cuden: Yeah, I interrupted you. Mark.

Mark Gunn: I was going to say that we. We have that outline, then we go to write the script and then at some point realize that the outline sucks and we have to conceive it that, you know, and that’s part of as, you know, that’s part of the writing process.

Steve Cuden: It is. It is.

Mark Gunn: Rewriting is. Is realizing you took a wrong turn. Is realizing that some idea you had that you thought would work doesn’t really work or it doesn’t fit in the story. Or this character is uninteresting and you got to go back and rewrite it. And that is a big part of our daily lives, is rewriting, which it is for every writer. It kind of has to be.

Brian Gunn: Yeah, it has to be. If we get stuck on a scene, for more than a day or two, usually that means that we took a wrong turn, earlier in the process. Because when the outline is right and when the ideas are right and your basic, core concept is correct, it’s easy to write because everything falls into place. You’ve done all the foundational work is there. and then when we just get stuck and we just have no clue what we’re doing, we usually bang our heads up against a wall for a good 48 hours. Then we realize, you know what? The problem wasn’t really this scene. It was actually what happens on page 30. It’s not what’s going on in page 60. And because of that, we have no idea what we’re doing. And it’s like trying to build a house on sand. so usually we have to go back and tear things up by the roots a little bit.

Steve Cuden: That, for me, is the problem with the folks that you described earlier, who just write scene one and go from there and try to figure their way. I think that leads to all kind of dead end alleys and blind turns and you don’t know what you’re doing. To me, I’d rather figure it out in advance and then write your script from a decent outline. Even if it’s wrong. Even if it turns out to be wrong.

Brian Gunn: Yeah, we would, too. I just think that sometimes some people are fine writing, like 100 drafts. That includes dialogue and everything, and throwing out, tons, of material to get where they need to go. So it’s just like they’re throwing all that clay down constantly. I don’t begrudge the people, for whom that works, but it would not work for us.

Steve Cuden: Do you have a particular technique for developing characters?

Mark Gunn: I don’t think so. For characters, I mean, one of the sort of traps of doing what we do for us anyway, or for me at least, is relying on characters that I’ve seen in movies and tv shows to be, like, starting point for a character that we’re creating. And it’s usually much more interesting if it’s. If you’re inspired by someone you know in life, someone you’ve dealt with, someone you’ve. Someone that you care about, someone that you’ve heard about. Those characters tend to be, more. Feel more alive than the ones that you’re just inspired by other tv shows or movies. That’s something that I personally have to work on a lot, is trying to stay away from, resting on characters, that someone else created and trying to create fresh, new ones.

Steve Cuden: You have to avoid the trap of, making it like some other character you’ve seen and liked.

Mark Gunn: Yes, exactly.

Steve Cuden: So one of the things that I talk about a lot with other up and coming screenwriters is that what you’re talking about has a tendency for a lot of writers to turn into two dimensional characters. There’s no depth to them because you’re writing something that already exists rather than something you’re creating fresh and three dimensionally. Yeah.

Brian Gunn: There’ll be characters that you’ve seen for, maybe 2 hours on screen somewhere else, and suddenly you’re, you know, those are characters you don’t really know. But I remember especially early on in our career, we would write these characters that we. These sort of big, bombastic guy characters. and, we kept realizing, oh, my God, we’re writing our dads. but we know our dads so well. And, you know, I thought my dad, my. They’re very larger than life characters. I thought, my dad was, just like, just a really funny person. He was. He was funny, despite himself. And also funny just because he was a funny guy. And, we would just be drawn to these guys who are like these somewhat, overbearing, lovable, bombastic guys. We’re like, oh, my God, we’re riding our dad. There’s almost no one we knew better than our dads. And there’s almost no one we ever talked, talked about, more with our friends and told stories about than our dads. And so it was easy to draw on that well of inspiration. very, very different than trying to write, you know, you’re gonna write the main character from Lethal weapon or something like that. I don’t know.

Mark Gunn: And it helps that Brian and I grew up together because we both know each other’s dads really well. We know our each other’s siblings really well. We know each other’s moms really well. We went to the same high school. We went to the same college. We have our reservoir of characters based on real life people has a lot of overlap. And that helps us as partners. And that’s something that we have that I think a lot of other partners probably don’t have. Is that really, really deep, reservoir of real life characters?

Steve Cuden: Do your dads both know that you both think of them as bombastic?

Mark Gunn: I would say, honestly, Brian’s dad was more bombastic than my dad. My dad has other qualities, but they’re both interesting. That’s the thing. They’re both, to us, they’re just interesting characters that sort of jump off the page in real life. You know, they have qualities that in real life are interesting and sort of leap off the page. And then we have to encourage that when we write them as characters to make them exaggerated versions of themselves.

Steve Cuden: Are the two of you people watchers? Do you like to go out and watch people?

Mark Gunn: I do. I love meeting new people and talking to new people and just listening to their rhythms and the way they talk and what their fascinations are and what their sort of hangups are. And I find all that stuff really interesting.

Brian Gunn: Yeah, I agree. I used to. I, when I was single, I married now, but when I was single, I went on a lot of dates. And I. And I would. Sometimes I would be set up with someone or I would meet someone through, like, a dating app or something. And I would, and I would, and I would sit down in the first few minutes of the date, I would, I would realize, oh, my God, I have nothing in common with this person. I definitely think this is like, I’m gonna have to suffer through this dinner. And I would always tell myself, I was like, you know what? I think I can connect with any single person on earth if I just find the right stepping stones to get to sort of relate to them. And always, always, if you sort of ask the right questions and, you’re listening, you will inevitably find that everybody’s fascinating. Everybody has a whole universe of feelings and dreams and thoughts and aspirations inside of themselves. And, our goal as people, connecting with each other is the same as our goal as writers is to find those people when they present themselves to us.

Steve Cuden: So then once you have found, okay, you’ve got a story idea, you’re starting to work on it, and, you know, you need this character, you need some form of characters throughout the story, because that’s what you’re going to do, is you’re going to put characters in conflict with other characters. That’s standard stuff. What do you then do? Do you actually sit down and draft out some form of a bio on different characters, or how do you do it?

Mark Gunn: We do do bios. Oftentimes the main thing for us is why should the audience be emotionally invested in that character’s journey? And what is their journey? What is their arc? How are they, how does this, the experience of this story, change them over the course of an episode or a season or a movie, if it’s, the course of a movie. And so oftentimes that’s one of the starting points, is trying to figure out how they change, because there always has to be change, otherwise it’s going to be flat. And why do they change? And why do they need to change? What’s their problem at the beginning of the story that gets solved by the end, or how does it get worse by the end? And so oftentimes we’ll take just a kernel of an idea and then, as Brian said, we’ll blue sky it and just come in and pitch each other ideas for what that character could be. Where do they go? How do they get to where they are now? What do they become at the end?

Steve Cuden: Do you try to develop that kind of arc for every character or just the principal characters?

Brian Gunn: To be honest, I mean, I don’t.

Steve Cuden: Mean secondary and tertiary characters. I mean for the principal characters.

Brian Gunn: Usually it’s just for the main principal characters, to be honest, there are people who are characters who appear as sort of runners or something. They might not, change much, or if they do, it might just be they start off a and they become b and it’s not terribly complicated. So I would say that we, you know, for characters who might only appear in a handful of scenes, they’re not as likely to have as, gripping of a character arc.

Steve Cuden: Do you ever find that those characters that you don’t develop as well, you suddenly have to, later on, go in and figure out ways to make them.

Mark Gunn: A little more deep all the time. We will finish a draft and feel like it’s in good shape and then realize this character who’s not a main character but an important character is flat and they don’t really have much of a story. They don’t have much of, an arc or. And when you don’t have those things, it’s not. You’re not going to be emotionally invested in that character in any way. And a lot of times for these stories, you need, we realize, oh, that character is actually important and we need to be invested in that character, and so we’ll have to go back and. And work on that character for us.

Steve Cuden: So more of the development process of the script, and I’m just curious. I’ve already spoken about revisions and how important they are and how many typically, how many drafts do you do on a, you’ve got a finished script, you’ve completed it. But then how many drafts do you revise, typically, before you then give it to someone else in power, not necessarily a friend or a colleague, but someone in power that you are trying to get money from or approval from. How many drafts typically do you do?

Brian Gunn: It’s so hard to say because, usually we’re not writing from, you know, we’re not doing a page one rewrite on our own stuff every time out. So there might be some scenes that we write. We might write only once, and we feel like we basically got it. We got it at least good enough, for other, eyes to see it. And then there might be other scenes that we rewrite over and over and over and over and over. So, it’s hard to say like what a draft is in a situation like that. I would say that, more and more, the more we go along, I would say we only write a few drafts, a couple drafts just, between ourselves before we show it to, either the producers or the studio or even sometimes our agency.

Steve Cuden: Is that because of this long drawn out process that you have where you have long conversations and you’re. You probably have a pretty good clue prior to even drafting the first sit down.

Brian Gunn: That’s all part of the iterative process. Those are all parts of drafts. A have a firmer idea. But also, we used to get everything absolutely perfect before we showed it to, a producer or something like that back in our, early on in our careers. And we realized that so many times the producer would come in and have just some core concept, some big structural change that made all of the sort of, I dotting and t crossing kind of superfluous. And so it was just a waste of time. And so again, it gets back to what you asked earlier about collaboration. We see it much more of getting out a sort of provisional draft to people so they could get their hands on it and they could tell us how to move in this direction or that direction. And then we could go back and we could work on that, ourselves. So we’re much more apt now than we were earlier in our career to send along something that’s sort of knowingly imperfect, before we get notes, from other people.

Steve Cuden: I think that’s a huge advantage for you. And a solo act like I am, or people that are solo act, it’s a little more mysterious because you’re not bouncing off of other people and you kind of have to trust, okay, I’ve finished whatever I’ve done. Now I’m going to hand it over, and then you cross your fingers big time because you’re not really sure.

Brian Gunn: I mean, to be fair, we do have the luxury of, like, some of these people. You know, we’re not giant, a list writers who can, you know, throw crap around town and people will automatically, you know, read it anyway. but I will say we’re more. It helps to be a little more established because earlier in our career, if we wrote something that was, you know, pretty subpar, and, a producer or studio might read that and just move on. even if you owed them further drafts, they might not read it in the most generous spirit, and they might just be like, you know what? We’re done with these guys. So, it helps for someone to say, look, they can turn in something and it can be less than perfect, but I trust that they’re going to get there and they’re going to do a good job because we’ve worked with them in the past and we know their work and so on.

Steve Cuden: What would you say, are the things that newer screenwriters don’t do, to make sales. What are they missing? Or what would you say that they would help them to make sales in the future?

Mark Gunn: Well, I would say one of the. For just for any aspiring writer, it’s important to rewrite, when you, it’s so tempting. When you get to the end. Let’s just talk about screenplays for a minute. You get to the end of a screenplay because it’s taken such a, it’s such a battle just to get to that point, just to write, you know, 100 pages of a story to feel like it’s finished, it’s done, it’s not finished. You need to go back as if someone else wrote it and gave it to you and asked for notes and be really hard on it and rewrite it. And, you know, at some point, there’s a, there’s diminishing returns on rewriting your own work. And you have to put it aside and say, now it’s ready to send out. And that is a hard, a hard moment to find when, when it’s ready to send out. But I can tell you it’s not ready to send out. After your first draft, you really have to go back and rewrite and ideally ask other people for their insights and thoughts. And even if you don’t agree with their criticisms of your work, there’s probably something that led to them giving that criticism that isn’t quite working in the script that you could then try to figure out and work out. So, you know, to me, the biggest key is rewrite. You got to rewrite all the time.

Brian Gunn: And also, you know, this is a little bit what you were asking earlier about having a distinctive voice. But the biggest mistake m we both read a lot of scripts from aspiring screenwriters and almost, unilaterally, they are smart, and literate, and everything is in the right place. And they clearly read, screenwriting text, and they followed the hero’s journey and all those things, and they’re fine, but they feel derivative, they feel flat on the page. and so the thing that’s usually missing most from aspiring writers is just going for broke, cutting loose, unleashing whatever own voice they have, and trying to do something that’s genuinely fresh. The very first thing that I, one of the first things was, I guess, was the first screenplay we ever wrote together, mark, and I was, it was something called, Bender. And it was this. We wanted to basically see what would happen if you did a go dar is a Marx Brothers movie.

Steve Cuden: And say that again. Godard, as a Marx M. Brothers movie.

Mark Gunn: Yeah, like Jean Luc Godard. We were into Jean Luc Godard. This is like, you know, when we were much younger. And we liked the just sort of anarchy of his movies, but the literate anarchy of it. And then we also love, like, the mark, the physical comedy, the Marx Brothers.

Brian Gunn: And we tried to break as many rules as we could with the screenplay. It’s about this one crazy night among these group of friends. And it was. And, so wild. and it was, you know, like we had the end credits in the middle of the movie. We had, like we did. We did everything that you’re not supposed to do, but it was, it was fresh and it was real. And when we, when we were first searching for a manager, that’s the writing sample that we gave him. And he loved it because it was like nothing he’d ever read before. So again, I wouldn’t necessarily encourage, an aspiring writer to break every single rule, but, but, But, but definitely break some rules, do some stuff that’s, that’s, you know, don’t worry too much about, getting all the steps just right, because.

Steve Cuden: What’S, what’s the famous adage of producers and executives where they say, I want something completely unique and different, just as long as it’s the same as everything else?

Brian Gunn: Yes. Yeah, yeah, yes.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Brian Gunn: That’s very true.

Mark Gunn: I mean, one of the challenges as a, as a, for any writer is people who, if you’re trying to break in, the people who are going to read your script are people who read a lot of scripts and you do not want them to be bored. You can’t. Like that is one of the biggest enemies is writing a competent screenplay is going to bore them. You have to have surprises. You have to, you have to try things. You have to take big swings because competence isn’t enough.

Brian Gunn: The phrase that we probably quote more than any other. This is also by Chris McCrory, whose, advice I think is really great.

Mark Gunn: He’s like, writer director of the last few mission Impossible movies and needed usual suspects.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. So he said, why be good when you can be awesome? we take that to mean there’s all kinds of stuff that we do all the time where it’s like, you know, this doesn’t make total sense. I don’t know if we can completely justify it, if it’s the quote unquote correct move here, but it’s so cool and it turns us on. And so we more and more just lean into stuff that we think that provokes a reaction. And, so I would say for a young writer, do those things that you just think are awesome, even if they’re not quote unquote good. you know, if they don’t follow.

Mark Gunn: The rules or they don’t toe the line of what you’re supposed to do in a screenplay, go for it. Go for it.

Steve Cuden: Well, people are, people tend to be a little bit afraid of going over the line because they think nobody’s going to accept it.

Brian Gunn: Yeah, yeah, yeah. You got to remember, like, what mark just said. you got to remember the people reading these scripts. They read 1000 scripts a year, and they’ve seen everything, and so try to come up with something that maybe they haven’t seen.

Steve Cuden: Yeah, for sure. And that is difficult for a young writer to do. And if they get way outside the box, then they aren’t going to get hired. But being outside somewhat is the way to go.

Brian Gunn: Yes.

Mark Gunn: Yeah. It’s hard to find that line. Like, it’s, it’s, that’s one of the challenges of being a screenwriter, and especially an aspiring screenwriter, is, is how far can I go? And you just have to try stuff and see what kind of reaction you get and be smart about it.

Steve Cuden: So that leads me to ask about this thing that we all go through, which you’ve already alluded to, which are notes. You have both received notes and you have given notes, but as an executive producer, as a producer on a tv series, you’ve given out notes to people, and you’ve gotten a lot of notes on various things you’ve done. What is your attitude toward notes, note taking and note giving?

Mark Gunn: Well, one of the things about note giving to me is, and it’s always surprising, there’s so many producers who give us notes who don’t seem to understand this is, it really helps writers when you’re telling them what they did wrong, to also tell them what they did right. Tell them what works. Even if it’s a small thing, tell them what works, what you like. It helps give them a roadmap when they’re fixing the things that you didn’t like to know what to shoot for. Because if it’s just a series of criticisms of what doesn’t work as a writer, a, it’s demoralizing, but b, it doesn’t really, it doesn’t help as much as to figure out where you need to go with your next draft when you’re doing those notes, if you have no idea what you’re shooting for. So try to be encouraging as well as critical.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. Another thing when you’re giving notes is to try to, don’t be so prescriptive. Usually when we get notes, you know, the, the person will give. I wouldn’t say usually. A lot of times when we get notes, they say, here’s what it should be, or here’s what the answer is, or here’s how I’m seeing it. And a lot of times they’ll even say, here’s, the bad version, but they don’t really want to. There’s not really the bad version. That’s actually a version they want to see in the script. And a lot of times, it’s really hard to work your way backwards from what the answer is. It’s much better if someone tells you what the problem is and what the, you know, and then we can go off and come up with creative solutions for it. So, you know, that that’s definitely. In terms of, giving notes. In terms of getting notes, nobody likes getting notes. I mean, I getting bad notes in particular. There’s nothing can ruin a week faster than that. But you have to go into it with a spirit that this person giving the notes is like your first little focus group, and if they don’t like your stuff and you didn’t get it right, you can’t sit there and argue for why it’s great, because they are an audience member and it didn’t work for them. And so, almost by definition, you didn’t really do your job. And you just have to take the notes with, with a, spirit of graciousness. And a lot of times we’ve gotten notes that we hate, and we spend the whole rest of the day griping about them. And then we find our way, you know, we start to hear the note a little, with a little more open ears, and we kind of realize, a lot of times, the note behind the note, and we realize, you know, what? They were right. And, if we do x, y, and z, it’s going to make it a little better, and maybe even if it doesn’t make it totally better, it’s going to at least make it something that they like more. And at the end of the day, that’s your job. We’re not. Again, they’re paying you, you know, like, so, they have a right to get what they want. And it’s your job to find that.

Steve Cuden: If you’re in the room and someone’s giving you verbal notes versus written notes, do you find that you tend to sit back and accept the notes and walk away and think about them? Or do you tend to actually argue a little bit about what’s being given to you?

Mark Gunn: We almost never argue because, as Brian said, it’s like, it seems ungracious and it’s, not productive. Sometimes you’ll get a note based on something that the person giving you the note, they missed something in the script, and they’ll say, this doesn’t make sense because you didn’t set it up. We’re like, just so you saw that thing on page 18, right? Where. And they’re like, oh, yeah, never mind, never mind. Like that. That does happen sometimes, but that’s not arguing with a note. That’s trying to help them along. And sometimes you say that, and they’re like, yeah, I saw that thing on 18. It still doesn’t make sense. And then you just say, okay, we’ll work on that. We’ll go work on that.

Brian Gunn: We heard, though, from a producer once who said we were feistier than most of her, writer. Because it’s a weird thing about screenwriters ways. I don’t know much about the job, of screenwriter, because they’re the only other people we don’t work with. I guess occasionally you meet screenwriters and you talk shop, and sometimes, we’ve been to parts of writers rooms and stuff like that. But I don’t know how other writers take notes. I’ve never been in a note meeting with other screenwriters. And so I don’t know what’s an appropriate level of pushing back. And we had heard that they said, oh, yeah, you push back more than most writers do. And I was like, oh, wow. But, you know, I don’t think we’re ever super defensive and thin skinned about it. It’s just sometimes you’ll get a note and you don’t agree with it, and you’re like, okay, here’s what we are going for. And we’ll be like, I’m not saying what we did was right. I’m just trying to. We all want the same north star here. And, I guess maybe we push back a little more than I think we.

Steve Cuden: Hollywood’s chock a block filled with bad notes.

Brian Gunn: Oh, my God.

Steve Cuden: We all know that. Everybody who’s ever received notes knows that half the time, the notes make no sense at all. Because somebody has got a job, and their job is to give notes. So you get notes whether you want them or not. The, ah, question is, how do you accept them? How do you then turn those around? Do you address all of them? Do you address only some. And there are all kinds of ways to do it. Mel Brooks famously would get the notes, and he’d say, that’s the best note I’ve ever heard. And he’d go off and ignore it and never do anything with it. And so that’s how he handled notes from studio executives. What you’re talking about probably is the ideal way to go. And so when you were working on your tv series, you didn’t have freelance writers coming to you at that point. Were you writing everything yourself?

Mark Gunn: No, we had a writing staff, so we had a staff that worked with us.

Steve Cuden: So then you were giving notes to writers? Yeah.

Mark Gunn: All the time. Yes. Yeah. And we tried to, you know, again, that was when we were first, that was like the first thing we ever did. So I’m sure we did it badly, but, you know, we tried to give the kind of notes that we want to receive that were, that were somewhat positive and built on what they were going for and tried to come from a point of understanding.

Steve Cuden: Here’s the truth. Nobody in Hollywood ever goes to school to run a show. Now, they do have a show running program at UCLA. A guy named Fred Rubin does an excellent job talking about how to run shows. But most m people don’t ever train to run a show. You have to just do it by being around and doing it. You guys, as you say, the challenge for you was you didn’t come up through the ranks where you watched others running shows. You just were slammed right into it.

Mark Gunn: You were thrown into the fire.

Steve Cuden: Baptism by fire. So I. Most producing and a certain amount of writing, but maybe writing less so. But most producing comes with a certain amount of pressure, various built in pressures. How do the two of you handle pressure when it’s coming your way, deadlines and details, and you’ve got to move. Now. What do you do with pressure?

Mark Gunn: Add hours to our day to come into the office and just work, just grind it out. that’s really all we can do.

Steve Cuden: You just keep banging away.

Mark Gunn: Keep banging away?

Brian Gunn: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: I mean, so it’s not meditation, it’s not going out for a walk, it’s not running, it’s not exercise. It’s none of those things.

Mark Gunn: I mean, I think we both exercise a lot anyway. and we have, you know, kids and families and other outside, stresses so that we’re all managing all the time. So it’s all part of that same continuum of stress management, I think.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. And you have to remember, too, that a certain amount of downtime and, reflection and recharging is part of the creative process. And a lot of times if we have, if we’re juggling like a few different jobs, and these deadlines are fast approaching, I will freak out and I will just think, oh my God, we’re never ever, ever going to get it done. What am I going to do? And I’ll think, we’re just going to have to work around the clock. I’ll sleep, you know, 5 hours a night and we’ll do nothing but write. And it’s like, that is completely counterproductive. Like, that is not you. You’re not drawing on anything. You’re not you’re not, you know, you don’t have any energy left over. And plus you’re fighting all this, anxiety and tension to be creative. I mean, it’s hard to be creative when you’re not being kind of loose and forgiving. And so as we’ve gotten older, I’ve realized much more that like, look, eventually everything gets sorted out. I’ve never been you know, even if you have to turn in a script a day or two late, we’ve never been arrested for it. And so it’s like everything is going to be fine. And sometimes just sort of letting go and realizing like, look, you just put 1ft in front of the other. You’re not, you’re not going to be helped by freaking out.

Steve Cuden: If you ever are arrested for it, it will make news.

Mark Gunn: That would be a dark.

Steve Cuden: So then how do the two of you refresh your, well, is it going to family? Is it going out to dinner? How do you refresh and come back with renewed energy?

Mark Gunn: What do you do for me? I’ve taken to, I swim laps every day. and just that act of putting my head in the water and swimming back and forth, back and forth is a sort of, for me, as almost like a form of meditation where I don’t go in with a plan to think about anything while I’m swimming. I just let my mind go where it wants to go. And a lot of times I end up thinking about a story problem that I know we have to work on later that day. But if my mind wanders away from that story problem, that’s okay too.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. You know, having dinner with my family, watching, baseball. Usually, the first thing we do in the mornings is we come in and we’re kind of on our separate laptops, kind of like perusing news and things like that. You know, any, anything that’s not screenwriting is, usually helpful.

Mark Gunn: We talk a lot about baseball in this office baseball.

Steve Cuden: It wouldn’t be the Cardinals, would it?

Mark Gunn: It might be Steve. It might be not a great season, 2023, for the St. Louis Cardinals.

Steve Cuden: But every season for the last 30 some odd years for the pirates has been misery.

Brian Gunn: So they finished ahead of the cardinals this year. So they’re on the way up.

Steve Cuden: They are on their way up. So I have been having absolutely one of the most marvelous conversations ever about Hollywood and screenwriting and just being in this business with the Gunns, Mark and Brian Gunn. And, we’re going to wind the show down a little bit. And I’m just wondering, you’ve clearly been around a bit and you’ve, met and worked with lots of people in the entertainment industry. I’m wondering, do you have an oddball, weird, quirky or offbeat or just plain funny story that you can share with us?

Brian Gunn: The first thing that we ever worked on was together. And I mean, this is not a fun or funny story, unfortunately, but it’s, The series ended after two seasons when one of our main characters, passed away. He was 16 years old. and that was just. I don’t think we’ve ever had anything wilder or weirder, happen in our careers, because what would happen is this, actor, this young actor would come in and a lot of times he would shoot about, half of the material, that he had. And then he was just. He became too sick to finish the day. And, so he, we would have to be spending like, these practical all nighters rewriting, the material around the scenes that he couldn’t finish. And then when he eventually, he eventually died. And, we had this footage that was. That we. From an episode that he had done some of the scenes, but he hadn’t done the rest of the scenes. We couldn’t go, you know, we couldn’t obviously reshoot his scenes, or with, you know, he was. He was gone. And so we ended up having to, shoot his scenes with, we had to find a voiceover actor who could mimic his voice. He had a very distinctive voice. And, we had to shoot. He did his. We wrote his scenes as if his dialogue was offstage. One time it was even. We had his character speaking from behind a, like a restroom stall or something, talking to another character with a voiceover actor who mimicked his voice. It was a kind of weird, horrible situation that we gutted through, but it was like we were really thrown into the fire, early on. The whole situation was just emotionally difficult, dealing with this. He was a great, great kid, who died way, way too young, and dealing with that, but also having to, produce content in the middle of all this around this person, who was no longer with us, was, That was definitely one of the wildest, weirdest things that we’ve ever experienced.

Steve Cuden: That sounds like it was not fun at all.

Brian Gunn: No, no, it was not. Not fun at the time. It was.

Mark Gunn: He was a great, sweet kid and, you know, think about him all the time.

Steve Cuden: I’m sorry to hear that. But it’s interesting because you actually, in doing that, have answered a question I do ask some guests, which is, how do you handle really extraordinarily difficult circumstances? And that’s a solution to it, is you worked your way around it with production. Yes, yes.

Brian Gunn: Absolutely. Yes. Totally. we found a way. I mean, all of it seemed sort of insurmountable at the time, and we just, we got through it somehow. but it’s, you know, we’ve never had jobs since where we’ve had to deal with anything quite that, tragic or.

Steve Cuden: And I hope you never do.

Brian Gunn: Yeah, right.

Steve Cuden: No kidding. Last question for you today then. you’ve already, along the way here, given us tons of really great advice, but I’m wondering if you have a single solid piece or maybe more than one piece of advice that you like to give out to those who are starting out in the business, or maybe they’re in a tiny bit and trying to get to that next level.

Mark Gunn: Well, I would say, for one thing, finish your script. and by finish it, I mean, as I said earlier, get to the end and then go back and rewrite it. But finish it, finish it, finish it. I know a lot of people start a script and sort of run out of steam and they can’t finish it. I think you’ll feel a lot better about yourself and about your create the creative side of yourself if you finish the script.

Brian Gunn: Yeah. And to build on what Mark said, I remember, Chuck Jones, the great animator, he had an art teacher once who told him that everybody has 10,000 bad drawings in them, and the sooner you get them out, the better. And I feel the same way about, screenwriting. You know, I feel like everybody’s got, you know, whatever, 10,000 bad scenes or 10,000 bad lines of dialogue or 10,000 bad ideas that they have to get through, and you just have to, you have to get them outside of yourself and you have to see them for what they are. And work with them. But every time you get rid of one of those bad ideas, you’re getting that much closer to a good idea. And so the only way, you know, in other words, the only way to really, succeed is by failing and to go through and, produce stuff. Try fall on your face, get back up, figure out what works, adjust nip, here, tuck there, do all that kind of stuff. But it’s really this volume, this production, that’s the key. So put yourself on a deadline, and be really, you know, be really, sort of forgiving towards yourself. Just really, you know, embrace stuff that doesn’t work. But the more you do stuff, the more you will figure out stuff, the better you will get. and I think that’s really, really key for any kind of, aspiring.

Steve Cuden: Writer wise pieces of advice from both of you, and I’m terribly grateful that you both, gave me your time and your wisdom today. This has been a lot of fun for me, and I’m very thankful that you came on the show today. Mark and Brian Gunn, this has just been fantastic.

Brian Gunn: Thank you so much, Steve.

Mark Gunn: Thanks for talking to us.

Steve Cuden: And so we’ve come to the end of today’s StoryBeat. If you liked this episode, won’t you please take a moment to give us a comment, rating, or review on whatever app or platform you’re listening to? Your support helps us bring more great StoryBeat episodes to you. StoryBeat is available on all major podcast apps and platforms, including Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, iHeartRadio, Stitcher, Tunein, and many others. Until next time, I’m Steve Cuden, and may all your stories be unforgettable.

0 Comments