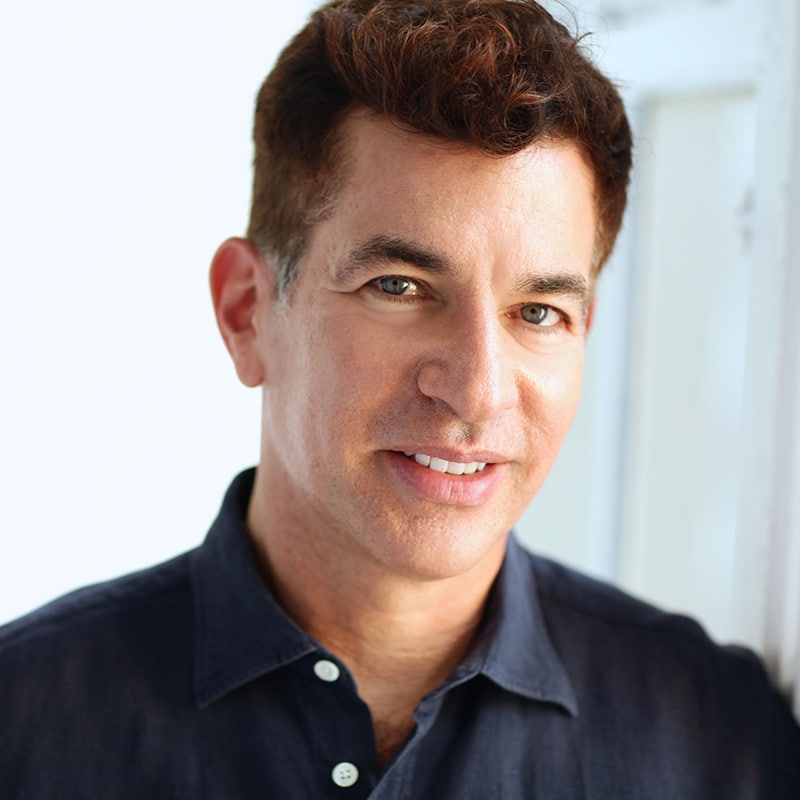

David Stenn was hired by the TV series Hill Street Blues immediately after graduating from Yale, becoming the show’s youngest writer ever. David then wrote She Was Marked For Murder, an NBC movie that earned an Edgar nomination from the Mystery Writers Guild of America.“And I said, I don’t know any editor. The only editor I’ve ever heard of is Jacqueline Onassis, and he said, she might be interested in this. And so he submitted the proposal to her…and that was it. The first time I went to her apartment…she came in and she gestured to the shelves of books, and she said, these are my friends. And I thought, I feel the same way….But the greatest gift she gave me at first was just this implicit belief that I could do this.”

~David Stenn

David returned to television as Producer of 21 Jump Street, then Supervising Producer of Beverly Hills, 90210.

David’s first biography, Clara Bow: Runnin’ Wild, which was published by Doubleday and edited by no less than Jacqueline Onassis, became a national bestseller. Variety raved, “Only rarely will you find a book that is as total a winner on every level as Clara Bow: Runnin’ Wild.”

His second biography, Bombshell: The Life and Death of Jean Harlow, again, edited by Jacqueline Onassis, was cited by the New York Times as one of the year’s notable books.

“It Happened One Night…At M-G-M,” David’s discovery for Vanity Fair of Hollywood’s best-suppressed scandal, brought vindication to rape survivor Patricia Douglas after sixty-six years in hiding and is now considered an historical progenitor of the MeToo movement. The story was adapted into Girl 27, a documentary film that David directed.

I’ve read David’s excellent book on Clara Bow and seen Girl 27. Both are powerful pieces about Hollywood’s long history in how power players treat both celebrities and those who wish to become celebrated.

David then served as Co-Executive Producer of The L Word and Supervising Producer on the HBO series Boardwalk Empire. His most recent screenplay assignments have been for Martin Scorsese; Leonardo DiCaprio/Warner Bros.; and Working Title.

David is a passionate supporter of film preservation. He serves on the Film Committee of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and Board of Directors at the UCLA Film & Television Archive in Los Angeles.

WEBSITES:

DAVID STENN BOOKS:

IF YOU LIKED THIS EPISODE, YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY:

- Joey Hartstone, Screenwriter-Novelist-Episode #302

- Stephen Cole, Musical Theatre Writer-Session 2-Episode #298

- Andrew Erish, Author-Teacher-Episode #291

- Brian Gunn and Mark Gunn, Screenwriters-Producers-Episode #272

- Wayne Byrne, Author-Film Historian-Episode #260

- Robert Crane, Author-Episode #252

- George Stevens, Jr., Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #250

- David McGiffert, First Assistant Director-Author-Episode #242

- Jay Moriarty, Comedy Writer-Producer-Episode #241

- Stephen Rebello, Author-Screenwriter-Journalist-Episode #226

- Scott McGee-TCM-Director of Original Programming-Episode #211

- Alan K. Rode, Biographer-Film Scholar-Episode #208

- Stephen Galloway, Author and Educator-Episode #206

- Jon Krampner, Journalist-Author-Episode #197

- Scott Myers, Screenwriter-Teacher-Episode #193

- Shannon Bradley-Colleary, Novelist and Screenwriter-Episode #182

- Martin Casella, Playwright-Screenwriter-Episode #157

- Marley Sims, Actress-Screenwriter-Episode #129

- Rocky Lang, Author-Producer-Session 2-Episode #104

- Andy Tennant, Screenwriter-Director-Episode #92

- Stephen Cole, Musical Theatre Writer-Episode #78

- Rocky Lang, Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #67

- David Silverman, Screenwriter-Producer-Therapist-Episode #63

Steve Cuden: On today’s StoryBeat:

David Stenn: And I said, I don’t know any editors. The only editor I’ve ever heard of is Jacqueline Onassis, And he said, she might be interested in this. And so he submitted the proposal to her, and she made this preemptive bid, and that was it. The first time I went to her apartment, I went into her library, and she came in and she gestured to the shelves of books, and she said, these are my friends. And I thought, I feel the same way. So I think both of us really were simpatico in that sense. But the greatest gift she gave me at first was just this implicit belief that I could do this.

Announcer: This is StoryBeat beat with Steve Cuden, a podcast for the creative mind. StoryBeat explores how masters of creativity develop and produce brilliant works that people everywhere love and admire. So join us as we discover how talented creators find success in the worlds of imagination and Entertainment. here now is your host, Steve Cuden.

Steve Cuden: Thanks for joining us on StoryBeat. We’re coming to you from the Steel City, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My guest today, David Stenn was hired by the tv series Hill Street Blues immediately after graduating from Yale, becoming the show’s youngest writer ever. David then wrote She Was Marked for Murder, an NBC movie which earned an Edgar nomination from the Mystery Writers Guild of America. David returned to television as a producer of 21 Jump Street then supervising producer of Beverly Hills 90210. David’s first biography, Clara Bow Running Wild, which was published by Doubleday and edited by no less than Jacqueline Onassis, became a national bestseller. Variety raved, only rarely will you find a book that is as total a winner on every level as Clara Bow Running Wild, his second biography, Bombshell, the Life and Death of Jean Harlow, again edited by Jacqueline Onassis, was cited by the New York Times as one of the year’s notable books. It happened one night at MGM. David’s discovery for Vanity Fair of Hollywood’s best suppressed scandal brought vindication to rape Survivor Patricia Douglas. After 66 years in hiding and is now considered an historical progenitor of the hash Me Too movement. The story was adapted into Girl 27, a documentary film that David directed. I’ve read David’s excellent book on Clara Bow and seen Girl 27. Both are powerful pieces about Hollywood’s long history in how power players treat both celebrities and those who wish to become celebrated. David then served as co executive producer of the L Word and supervising producer on the HBO series Boardwalk Empire. His most recent screenplay assignments have been for Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, Warner Brothers, and Working Title, David is a passionate supporter of film preservation. He serves on the film committee of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and board of directors at the UCLA Film and Television Archive in Los Angeles. So for all those reasons and many more, it’s my distinct privilege to welcome to StoryBeat the screenwriter, producer, director, and biography, David Stenn. David, welcome to the show.

David Stenn: Thank you, Steve. Thank you for having me.

Steve Cuden: Oh, it’s a great pleasure to have you here, trust me. so let’s go back a little bit. What were your earliest inspirations and influences? When did you first think to yourself, I want to be involved in Hollywood in some way? Maybe as a writer,

David Stenn: I had inspirations. I don’t think I ever could have possibly dreamed I would be doing what I ended up doing, because I grew up in the midwest and I didn’t know anyone in the business. But when I was seven years old, my parents took me to see Lillian Gish. She was appearing at Goodman Theater in Chicago, and she was touring with a book she had written called the movies Mister Griffith and me. And it was her way of trying to introduce new audiences to the work of DW Griffith, the director and silent film in general. And she showed clips, and one of the clips she showed was from way down east. And it is the famous scene on the ice blow, where she is lying on her back with one hand in the water as Richard Barthelmas, who is wearing this heavy raccoon coat, is leaping from ice flow to ice flow. And at the very moment she’s about to go over the falls, he snatches her away and carries her to safety. And I was enthralled.

Steve Cuden: And they did it for real, didn’t they?

David Stenn: Well, that’s right. At the end of the clip, the lights came up, and Lillian Gish, who was a very small person, held up one of her wrists, and she said, to this day, when it’s cold, I can feel an ache in my wrist. And I thought to myself, that’s it. I have to know everything about these people. I have to know everything about what they did. I have to know all about them. And I became sort of an autodidact who read at seven, I remember I read Charlie Chaplin’s autobiography. I read everything I could. And that interest had started there.

Steve Cuden: And you weren’t turned off by the fact that most of these movies, or all these movies were black and white. It wasn’t color. There was no sound except for music. You had to read the cards. None of that turned you off.

David Stenn: No. In fact, I felt and I still feel that silent film is actually more evolved than sound film in the sense that it speaks a universal language. So a great silent movie, you don’t need words, and you have to imagine so much more. I mean, you have to imagine what they sound like, which is why a lot of the actors in silent films had difficulty transitioning to talkies, because how do you exceed 100 million expectations when everyone in the audience has their own specific idea of what your voice sounds like? You can’t possibly satisfy them all.

Steve Cuden: I think that that’s really dead on. And, in fact, we’ll get to Clara Bowen a bit. And she had that issue, didn’t she?

David Stenn: They all did, yes.

Steve Cuden: Unless they really had well trained theater voices already.

David Stenn: Yes, but even then, did their voice match their screen Persona?

Steve Cuden: Oh, well, that’s true. Did the voice match the Persona, which is really kind of the reverse of radio, where you’re hearing the voice and expecting to see a person that looks like the voice and they often look nothing like their voice.

David Stenn: That’s right.

Steve Cuden: So when did you start to write? Was it that early?

David Stenn: Probably. But again, I had no consciousness of being a writer. I remember in school I was always singled out for my writing, but it didn’t mean much to me because what do you do with that? I didn’t know any professional writers. I didn’t even know you could really do that. So it was something I guess I was good at, like being a good athlete. But you don’t necessarily think, oh, this is a career.

Steve Cuden: So that’s a common theme that I hear in this show, is that frequently young people who aren’t in the arts or their parents aren’t in the arts or they’re not in an arts center like you’re in the midwest, not in New York or LA. Frequently, young people don’t think there’s any opportunity to be a writer or a filmmaker unless you’re in those places. But in fact, that’s not true.

David Stenn: I think it’s even more premature than that. It’s not even an opportunity. It’s a consciousness. You don’t even have the consciousness of, oh, I could do this and make a living.

Steve Cuden: And you decided around seven years old that you were going to spend time and energy devoted to looking at, if not working toward, chronicling older movies and older actors and actresses?

David Stenn: Yes, it was pretty inexplicable to my parents. And I would try hard as I could to stay up late, you know, to watch the Late show where they would show movies. And of course, I’d fall asleep and wake up the next morning and be angry. But I remember I wrote a letter to the program director at The Local television station, WGN, and I. It was a three page, letter of titles, film titles, that I was requesting they show. And the phone rang a few weeks later, and my mother answered it. And I could tell by her facial reactions. She said, no, he’s at the office. And then she looked down at me and she said, well, he’s right here. What do you want to talk to him about? And it was the station calling saying, who is this person? They thought, obviously it was an adult. They didn’t realize it was a nine year old kid by that point.

Steve Cuden: Well, yeah, I’m sure that they were as surprised as your mom.

David Stenn: They probably were very curious about who had bothered to send this list of very obscure titles.

Steve Cuden: So eventually, you go off to Yale. What did you study there?

David Stenn: English.

Steve Cuden: English. So you were at least in that part of the world. It wasn’t like you were studying, you know, psychiatry or something. You were studying English.

David Stenn: True, but I only studied that because I wanted a really solid liberal arts education. I felt very fortunate to have been accepted, very fortunate to be there. And I thought, I’m going to get a good education here. I’m going to read all the great books that I might not read on my own. I still didn’t ever see myself doing anything creative for a living.

Steve Cuden: Well, this is the interesting question, then, because you’re the second person in my life that I know. And in fact, the second person who’s been a guest on this show, who got hired into Hollywood straight out of college, the, ah, first being Rick Hawkins, who wound up on the Carol Burnett show straight out of college. How did you get onto Hill street blues, of all shows, straight out of Yale?

David Stenn: It was really fortunate. what happened was I went out there and I had this vague idea maybe I could be an agent. And then I met some agents and thought I could never do this. So I did read a lot of scripts because I was just so interested in the business, and a lot of them were not very good. And someone I knew who was working out there at the time said to me, well, you think you’re so smart, you try it. And I thought, you know, the worst thing I could do is suck. I mean, that’s the worst thing. So I thought, all right, I’ll try it. And I wrote a script, and it’s sold. It’s sold to a producer named Jerry Abrams, the father of JJ Abrams. And I didn’t think it was particularly good. So I wrote another one that I put more heart into, and I thought that might be good, but I still wasn’t sure. So I had read about David Milch, who had taught at Yale, and he had written a script for Hill street blues while he was teaching at Yale. And it sent it in and it won an Emmy. And then he went out to Hollywood and started working on Hill street blues full time. And I did not know him in college, but I, wrote him a letter, and I said, everybody out here lies. I wrote a script. I’m not sure if it’s any good. If you have time, could you possibly read it and tell me the truth? Because if it’s bad, I’ll stop. And I put it in an envelope and I addressed it to him and I put it in the mail. And a few months later, he called me and he said, would you like to have lunch? And I said, of course I would. So I went to lunch with him, and he said, your script is good. Would you be interested in writing for Hill Street Blues? And I said, no, thank you. I didn’t have a television set in college, so I’ve never seen it. And I went home that night and I thought, you idiot. So I called him the next morning and I said, I’m an idiot. Can I have a second chance? And he said, yes. And they gave me, it must have been their third season because they gave me 52 scripts to read and said, let us know what you think of these tomorrow. I’d never pulled an all nighter studying in college, but I read 52 scripts. I stayed up all night, and the next morning I went in and they said, this is what we’d like you to write. Turn it in next week. And I did. And David called me at about 845 the next morning and said, this is good. We’re putting it into production next week.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

David Stenn: It was like a fairy tale. It doesn’t happen today.

Steve Cuden: Oh, it doesn’t happen hardly ever.

David Stenn: And people say to me now when they’re starting out, so the younger writers I mentor tell me how you started. And I say, well, I don’t think I will because you’ll put your head in the oven. Yeah, it was really wonderful. And then they hired me for more. And working in my initial experience professionally out there with people like David and Steven Botchko and Roger director, and Mark Frost and Jeff Lewis, I idolized all of them. And I just sat in that room, and I was smart enough to keep my mouth shut and my ears open, and it was just a wonderful introduction to the business, because working with people that were so a talented b scrupulous and who taught me how to not only be a better writer, but to be a better person in that world, M which becomes very important on a television series because you’re with the same group of people for long periods of time, unlike a movie you were working.

Steve Cuden: On one of the groundbreaking television shows in history.

David Stenn: Yes.

Steve Cuden: I mean, it really broke ground. The way they told stories, the way they treated characters, all of that was groundbreaking.

David Stenn: It did. And one of my shows was called you and me, M babe, ewe. And it was about Hill and Renko. Find a man dead in bed with a sheep. And how will they tell his wife? And I wrote it and turned it in. And standards M and practices at the network said, absolutely not. We will not air this. And I thought, well, there goes my career. You know, it’s over as soon as it began. And Steven flew to New York to meet with them and said, this goes on the air. And I never forgot that because he didn’t have to do that for me. He could have had another script written. And what he said went, and the show aired, and he gave me a career.

Steve Cuden: Well, that not only just exceptional, it’s truly extraordinary. It just doesn’t happen.

David Stenn: It happened to me. I mean, it was a miracle, but it also taught me how to pay it forward in the sense of helping new people, like, they helped me fighting for material, which is why that show was so good. The fact that their standards were so high of themselves and of everyone else, and they were tough, they were demanding, and I really responded to that. And there were times when they could be very critical, but I would think to myself, okay, David Milch is a genius. Just listen to what he’s saying, not the way he’s saying it, because he’s helping you.

Steve Cuden: And, you know, sid the snitch has been on this show, Peter Jurassic. And he was just wonderful to chat with. So I am curious. How did you learn how to write the first script you wrote if you weren’t taking screenwriting classes?

David Stenn: I don’t know. I think maybe, honestly, I always say I never went to film school because I went to the best university to learn how to write a script, which is to watch the masters.

Steve Cuden: Sure.

David Stenn: I had seen so many movies that by the time I actually tried writing scripts, I could say to myself, well, if I do this, it won’t work because they did it in such and such, and it only worked this way. And I had a real sense of listening, not only watching, but listening to Billy Wilder, listening to John Lee May, and listening even to Mae West, just the way they wrote it, instructed me in a way. It’s like the Greeks, you know, reading there’s nothing new under the sun. It’s just how you execute it, how you tell the story.

Steve Cuden: Oh, for sure, there are no really no new stories. It’s all execution and way you, points of view and all the rest of it. But I’m wondering, I’m still wondering how you understood the mechanics of writing a script. Had you just read a lot of scripts?

David Stenn: I read a lot of scripts, and, uh-huh. See, the ones that worked. And so I would sort of autopsy them in my head. I would say, why did this work? What made it work, or why didn’t this work? Why doesn’t this work? And there were certain writers that had a style that I admired, which I said, well, I’m not going to steal their style, but clearly you can develop a sort of idiosyncratic style if you want. And I also learned, and this is really important, although it has nothing to do with writing per se, which is how to make something really readable, because executives are swamped with scripts, and if you can’t grab them in the first five to ten pages, they won’t stay with you. So how do you keep them reading?

Steve Cuden: That’s for sure.

David Stenn: Not content, but just for execution. How do you, what, in terms of a writing style?

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s what I was getting at, is that you come from English at, Yale, and you’re trained, I’m sure, to write in prose, not in a script style, which is a certain specific mechanical way of writing, as opposed to the storytelling, which is a whole other issue. But I’m talking about just the mechanics of what do you do with the slugline? How do you write action? How do you write dialogue and so on? Those mechanics on a page are specific to screenwriting, not to prose writing.

David Stenn: Yes. And I made plenty of mistakes. I overwrote like crazy. I would give parentheticals for actors until I learned that they hate that. Yes, I kind of directed as well, which I have no talent for and no interest in. But I realized, okay, directors don’t like scripts that do their try and do their job. Actors don’t like that. So I learned on the way, but I paid a lot of attention.

Steve Cuden: I’m so happy to hear you say that, because for years and years, I’ve taught that exact thing, don’t direct on paper, don’t tell the actors how to act. Let them do their job.

David Stenn: And you have to accept pretty early on, if you’re going to devote yourself to screenwriting, that you are part of an architectural blueprint rather than an author. The first thing a screenwriter signs is a separation of rights with the studio which releases their copyright. It’s the only, medium where the writer surrenders copyright. If you write books or plays, they can’t change a word without your approval. But writing, everyone can. So you have to understand it’s really collaborative. And I’ve met a lot of writers who are bitter about the fact that their scripts get changed or they didn’t turn out the way they wanted. And it’s a legitimate complaint sometimes, but at the same time, they have to realize going in, that that is just an occupational hazard. It always happens. Unless you’re the writer director.

Steve Cuden: Exactly. as you know, I’ve written a lot of scripts myself, and I learned very early on to be a mercenary about it. I’m going to do the best job I know how. I’m going to make it in my voice. I’m going to give them the best story that I can come up with. I’m going to walk away and hope that they give me my proper credit, and as long as they pay me, I’m good. You’ve got to be a professional in that way.

David Stenn: Yes. And you have to be dispassionate and somewhat detached and not take anything personally.

Steve Cuden: Sure, absolutely. If you do take it personally, you’re not going to last very long.

David Stenn: That’s right.

Steve Cuden: in fact, if you do take it personally, they’ll get rid of you as quickly as they can.

David Stenn: That’s right. Because being difficult is probably the worst thing you can say about somebody in that business.

Steve Cuden: So the opposite thing that you’ve done is you took whatever training you had at, ah, Yale in English, and then translated that into books, nonfiction books. And so was that something that you also had a passion for early on was coming up with stories about existing people, biographies.

David Stenn: I think I had a passion for truth and investigation. I think I always loved to find out things and to research. I love to research. so that was not something that was being fed or nurtured in my screenwriting career. And so I almost started doing it on the side in secret because I was just enjoying it. And at the same time, I met a man named David shepherd, who worked at the director’s guild who was responsible for saving a lot of silent films in the 1960s when the studios were discarding them. And so he was a hero to me, I just heard Alexander Payne introduce a film where he said, I want to thank my mentor, David shepherd. And I realized, oh, David shepherd helped so many of us. But, he started introducing me to a lot of these older people. Who were in their eighties, nineties, had worked in the period I loved so much. And I started hanging out with them. And they would tell me these incredible stories. And no one was writing them down. So I started taping them. And then I started talking. And they would one of them would say, well, have you met this one? No. Well, you have to meet this one. So they would send me. And I spent my twenties essentially hanging out with nonagenarians and octogenarians. But I worshiped them.

Steve Cuden: Like who?

David Stenn: Well, most of them were not names that you would know. They were people like Artie Jacobson, Billy Kaplan. People that were assistant directors or electricians or. So they were on set every day and they had long careers. So usually what I discovered pretty quickly was the actors were not the most interesting interviews. The people that really compelled me and fascinated me were the people that were involved in the nuts and bolts on a daily basis. And were not thinking of themselves. They were thinking of just the whole unit. And no one had ever talked to them before. And so they were very grateful that a, youngster, a guy who was 22, 23, was fascinated by. And I learned really quickly that if you ask general questions, you get general answers. But if you go in with specific questions, they will give you very specific information.

Steve Cuden: Of course, that’s really the key, isn’t it? The more specific the question, the better. This particular show is a question show, and I am somewhat general because I’m trying to get to a broader picture about things. But yet I try to get specific as much as I can. Because I find that fascinating. Like you do.

David Stenn: Yes. So I love that. I love doing that. And when I had the opportunity, I never thought, it was the same situation, really, as screenwriting. I never thought, oh, I can write a book. That seemed completely unimaginable to me. But I realized Clara Bow’s story was too good for a screenplay. And that she needed a major biography. I didn’t think anyone would be interested in a biography of Clara Bow. But my agent sent me to a book agent in New York. And he said, I think I can sell this. Which amazed me. And he said, what editors are you interested in? And I said, I don’t know any editors. The only editor I’ve ever heard of is Jacquelinessis. And he said, she might be interested in this and so he submitted the proposal to her, and she made this preemptive bid, and that was it.

Steve Cuden: okay, so you’ve rolled out of Yale straight into Hill street blues, and you’ve rolled in your first book into Jacqueline Onassis. That’s what I call kismet.

David Stenn: It was a fantastic experience, and it was important to me because I’d heard she was a good editor and dedicated editor. But I also felt that I was writing about someone who had been more maligned than anyone, possibly in the entire history of the industry. I mean, someone was sent to federal prison for an obscenity trial about what he printed about her. And, of course, she had been run out of Hollywood. So I felt like Jackie had dealt with enormous amounts of attention and judgment and also had integrity and would protect the book. I wouldn’t have an editor saying to me, hey, can you sex it up a little more? I mean, I was already writing about a sex symbol, so I just wanted to tell the truth.

Steve Cuden: Well, you were writing about the it, girl.

David Stenn: Yes.

Steve Cuden: So let’s go back a half a step. You had to have sent something to her to get her attention, to say, this guy knows how to write. He’s got a really good sense of what he’s going to do. What did you prepare for her to read?

David Stenn: You have to submit a proposal. That’s standard. I think it still is. And so I did that. And I think what she responded to was both the fact that I was a, 24 year old that was interested in writing a book about silent film, which is intriguing, I suppose, to start off with. But I also think that that proposal contained a lot of information that no one had ever found. No one had ever talked to all of these people. No one had ever obtained her family’s permission to get her medical, her psychiatric, her financial records. So I’d done my homework before I submitted the proposal. So it was really, a sort of package by the time I did that, because I knew I had to do that, I couldn’t just be a potentially good writer. I needed to have something really special in terms of my material. And I did say to her very early on, I wanted to treat this subject as if it were, the biography of a military or a political or a religious figure. In terms of the scholarship, I want there to be notes. I want there to be bibliography, because at that point, movie star biographies were a disreputable genre, and people read them thinking, I don’t know if I trust this. And there were no source citations and a lot of it. Even for somebody like me in Chicago, reading them would think, oh, that’s ridiculous, or that’s not true. And I wanted to tell the truth.

Steve Cuden: Okay, so you’ve got a subject that no one had really done as deep a dive as you ultimately did. How long did it take you to do all that research? Was it years of research?

David Stenn: Yeah. it was years and it never ends. And I am still. That book was published in 1988. I am still researching.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

David Stenn: Once the Internet opened up, things that nobody could have ever anticipated finding, source wise, I sort of mate for Life with all the work I do. So I am constantly. I’m still close to people I worked with on early shows, later shows. I’m still interested in the subjects because you never know what you’re going to find.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s true. In fact, the more that you dig sometimes, the more that you find that you don’t know.

David Stenn: Yes. And I just am fascinated by it all. And I’m always trying to find more and never thinking that I know everything. Because just six months ago, a Clarabo film that no one knew even existed, myself included, turned up in a parking lot in Omaha.

Steve Cuden: Yeah, I saw you post that online. That’s fascinating. How’d that happen, do you think?

David Stenn: Well, it’s a long sort of tortured story of how that print ended up in Omaha. But what was interesting for me was you think you know everything and, you are authoritative about a subject, and then something comes along that makes you realize, no, there’s always more room to learn. And that’s why it’s important to keep trying to learn, because Clara Bowe seems to have forgotten she even made that film. So nobody had any record of it. And it played in 1923 and then never played again.

Steve Cuden: So it’s been, what, 36 years since you published the book?

David Stenn: And.

Steve Cuden: Ah. So my question is, with all this extra thought and information that you’ve gained over time, are you going to publish a new edition of it at some point?

David Stenn: I might. I mean, you know, Instagram. I have an Instagram account now at Realdavidsten, and I put a lot of my archival findings, photos and clips and audio on there because people like to hear it and it’s an immediate way of doing it. I did a revised edition. The book has been in print since it was published, which is kind of miraculous. But I did a revised edition in 1999. And so I feel like you can do this forever if you want and drive yourself crazy. There’s nothing I found that materially changes the meaning and the ultimate facts everything is there. If I did, I would do it again. But at the same time, you have to sort of let go and let your children kind of fly.

Steve Cuden: And so, in other words, you’ve got to get past too much minutiae. You don’t need all that minutiae to tell the story.

David Stenn: I love the minutia, personally. But my first draft, I remember I had to cut 100 pages, and it was like removing an arm or a leg. But I learned really quickly that it’s not about. She was very helpful that way because she said something to me I never forgot, which was, be like Fred Astaire. Don’t let the hard work show. Because Fred Astaire looks like he’s dancing on the clouds, but in reality, his shoes are soaked in blood.

Steve Cuden: No question. And that’s what I’ve. I’ve also told people that for a long time, you see him effortlessly gliding across the screen. But what you’re not seeing are the literally hundreds and hundreds of hours of toil, sweat, and labor to get there.

David Stenn: Yes. And that’s. That’s something, as a writer, you can forget. It’s so easy to show off and say, look what I found that no one’s ever found before. And you have to stop yourself, because it’s all about the narrative and how to just keep people reading.

Steve Cuden: Well, at the end of the day, you’re telling a story. You’re being a storyteller.

David Stenn: Yes, but the question is, do you want to be this kind of storyteller who goes off on tangents or is showing off about how much story you have? Or do you want to be the kind of storyteller who seems to do something casually, and suddenly people are spellbound, and that is the Fred Astaire of it all.

Steve Cuden: It seems tossed off, like you’re just casually telling a story, but in fact, this mass amount of research and time to get there. So did you work from an outline? Did you know what you were doing before you started to write the book?

David Stenn: I did. Because writing nonfiction, you have, obviously, the parameters of truth that you have to stick to, and I think that makes it easier. I really admire people who write fiction, who write fiction, because I don’t know if I could do that. Because that.

Steve Cuden: What do you mean, David, you wrote Hill Street Blues and the l word. These are all fiction.

David Stenn: I mean, a novel, when you have to be sort of stylish and you have to make up, you can do anything you want. That. That is daunting to me.

Steve Cuden: Okay, this is fascinating to me. What are the differences then that are that you think that you can’t write a novel or you would not be good at it or you might not enjoy it or whatever it is you’re thinking. What is the difference between doing that and coming up with television stories and teleplays?

David Stenn: I think the difference is, and one of the reasons I love television and I’m so grateful that I got my start there, is it was my grad school, because the writers room is a fantastic place to be. You’re working with other people, some of whom are so talented, some of whom are so interesting, some of whom are both. And you’re all coming up with the series together. I mean, I don’t know if people realize this, but say on a show like Boardwalk Empire, the first six weeks to two months of the job, we’re sitting in there all day just talking story and character. We haven’t even got to the point where we’re mapping out the series yet, episode by episode. And that really allows you to create a world where everyone is contributing and everyone has their different point of view. And even though one person gets a credit on an episode, really, they’re written by committee almost, because we’ve all come up with the story And sometimes just because of the brutal schedule, you’ll say, all right, I don’t have time to write this scene. You take this scene, I’ll take this scene. And I remember I was doing a show with Darren Starr called Central Park West for CB’s, and I loved working with him. We had done 9020 together. And he came into my office on a Friday afternoon and said, what are you doing this weekend? And I said, I’m going to do this. I’m going to do that. He said, no, you’re not. Just got the script in for this new show. It’s no good. You and I are rewriting it over the weekend. And we wrote an entire show over the weekend and we had a great time doing it. But that is something where, to answer your question, if it were fiction, it would all be on me and doing it with someone else. It’s fun.

Steve Cuden: And you can knock out a script, like you say, over a weekend if you have to, but it’s really hard to knock out a novel over a weekend.

David Stenn: Correct. And you’re knocking out a script with characters that you’ve spent months knowing with other people.

Steve Cuden: Sure.

David Stenn: And I always say that, you know, your series is working when you get in the writer’s room and you’re having this animated discussion with each other, and one person says, no, he’d never do that as if the person was real. When you start talking about your characters as if they’re real, then it is real.

Steve Cuden: Oh, it gets even better in Hollywood, as you well know. So again, I’ll go back to me just for half a second, which is, I wrote 90 cartoons for Hollywood, and you can get into those situations where it’s a completely made up world that has nothing to do with humans or earth or anything else. And someone will say, that character wouldn’t say that. And you go, well, wait a minute. Can you tell me what ants would say in the movie? Ants? What do ants say?

David Stenn: I love that, though. I just find that to be the most wonderful. When those moments happen, I think to myself, you know, I’m not going to tell them this in business affairs, but I would do this for free because it’s like being paid to just be imaginative, and I would do that anyway.

Steve Cuden: Listen, it’s really important that you don’t tell them that you would do it for free, because they will gladly let you. If you don’t, my agent will say it.

David Stenn: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: You did work from an outline, but I’m curious, how did you think about the structure of it before you started? Now, that’s where you get to your outline. But what was your structural thinking? It was chronological, mostly.

David Stenn: Yes, it was chronological. I mean, there was an opening, sort of forward, where I kind of wanted to lure people in and give them an idea of, why read this? Why read about this person? Why is this person important? Especially because at the time, Clara Bow had been pretty much forgotten. It was very hard to see her films, and people didn’t know who she was. So I thought I had to not only represent her, but represent her and to say so. But other than that, it was really chronological. And I wanted it to read like a novel. I wanted her to leap off the page. I wanted her to be a living, breathing character, which she was. She was a real person. And I wanted to try and convey her personality to readers so that they could care about her, because I don’t think biography works when it’s dry or feels like homework.

Steve Cuden: Agreed. And I do think that the way you wrote it, it read like a movie. It read like she was a character in a movie, and yet she was real.

David Stenn: Well, thank you. I mean, I was very fortunate because her life was like a movie. I thought to myself at the time, if I bungle this, it’s my own fault, because this is a fantastic story

Steve Cuden: Well, I knew almost nothing about her other than the most surface y things about her. And I don’t think I’d ever seen a movie of hers prior to reading your book. And then I went and looked at a couple of them online. And so tell us about Clara Bowe. Tell us the overview of who she was and what the issues were that she dealt with most of her career in Life.

David Stenn: Today, she’s best known as the it girl, the original it girl. And it at the time, it today has the meaning, has shifted 180 degrees because it today means temporal or ephemeral. The IT restaurant, the it handbag. Back then, it was her and only her because she had a quality that transcended sex appeal, although it was a lot of sex appeal, but it became a quality that women loved her because they wanted to be like her. Men loved her because they wanted her. And she had a, sort of personification of the 19, the roaring twenties. But she also had immense talent, emotionalism that the screen had never seen before. So not only she didn’t break the mold, there was no mold before her. She was the first american sex symbol.

Steve Cuden: What years?

David Stenn: Well, she started in 22, she got huge in 26. And she retired in 33 when she was 28. So it was a relatively brief career, but a hugely impactful one. She was the number one box office attraction and she mesmerized a nation.

Steve Cuden: And she made how many movies?

David Stenn: She made 57 movies in 1925. She made 15 movies alone.

Steve Cuden: Oh, my goodness. Well, they were literally cranking them out.

David Stenn: They were literally cranking them out. And in fact, that was what finally damaged her career, was that her studio, Paramount, felt, we don’t need to put her in good material. People will see her in anything. So there was no career management?

Steve Cuden: Well, they didn’t know about careers then. It hadn’t existed.

David Stenn: MGM was smart. MGM kept Garbo off the screen for almost a year and a half. From the silent to talkie transition, Paramount gave Clara about two weeks. So it’s like taking someone out of the Super bowl and dropping them in the Stanley cup and saying, you’re on. So there were studios that were more careful with their properties than Paramount. Paramount at the time was just a huge factory. They owned more theaters than any other studio. And so they were just trying to fulfill their theater demands with product.

Steve Cuden: And if I understand correctly from reading the book, she was in many ways her own worst enemy.

David Stenn: In the sense that she lived an honest, forthright life. Yes, in the sense that she didn’t know how to play the Hollywood game. In the sense that she wasn’t ashamed that she was from a slum in Brooklyn or that her mother was mentally ill. Yes. Hollywood at the time was very preoccupied with its own social pretensions, because all of these people were outcasts. You know, they came from a time when the hotel said, no dogs are actors. So everyone wanted to put on airs. And Clara Bo felt like she wanted to be herself. She never learned how to play that Hollywood game, to her credit.

Steve Cuden: So in putting the book together, did you need to go obtain any kind of rights, whether rights for Life story or rights for pictures or anything like that?

David Stenn: Well, you always have to get releases for photographs. I, think, to me, what was really important was to get everybody so that I didn’t have someone where I would say, I wish I’d gotten to that person, but they wouldn’t speak to me, or I wish that I’d been able to reach this person. So her family was hugely important to me, and that took me about three years. Her son was the Rexbell junior, was the district attorney of Clark county, which is Las Vegas. He was a very, very intimidating guy. He had played football at Notre Dame and basketball at UCLA. And when I met him, I went to his office in Las Vegas, and he had just won his second term by a landslide. And I was really nervous because he had said to me, look, I don’t know why you want to see me. I will not cooperate with any, They had been so burned by what had been written about their mother, who at the time was really the punchline to all of these old Hollywood dirty jokes. And I thought, all right, he’s going to give me 20 minutes, if that. What can I do? What can I possibly do? I need him. So I thought, all I can do is show him what I’ve done, which is research. And I’m serious about this. I’ve done a lot of work already. So I went into his office, and he had his feet up on the desk, and he had his custom made cowboy boots. And he was looking at me sort of, you know, assessing me. And he said, well, you know, I don’t know much about that. I can tell you about mother’s childhood. You know, her mother died when she was seven. And I said, well, actually, her mother died on January 5, 1923, when your mother was 17. And here’s her death certificate. Would you like to see? And the tone of the meeting started to change because he sat up, he took his feet off the desk, and he reached for the death record, and he read it. I think anyone would have this reaction. You could see his family history coming alive to him in a truthful way. And he’s looking at me and he said, what else do you have? And I never left. We, spent the rest of the day together. And then he drove me to the airport, and his wife worked for the FBI. And he said to me, at the end of it, she says, to do anything you’d want. And I got on the plane to go home, and my life had changed because signed releases for everything that I had access to, he gave me releases for everything without even looking himself. And that level of trust that he had in me, it was, it galvanized me. Not that I wouldn’t have been this way anyway, but it made me think, all right, I have to do an absolutely flawless job because he is entrusting me with his mother’s story.

Steve Cuden: And you were more or less still a kid at that point, weren’t you?

David Stenn: 24.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s young. I mean, that’s really young.

David Stenn: It was young, but I always had a sense of what I wanted, and I always had a sense that the worst I could do, like I said before, was do something badly. And that didn’t frighten me.

Steve Cuden: you said that earlier, and I wanted to comment on it, and we got further downstream. But here’s the thing. I think that that’s incredibly wise. And it’s not common for people to think that about their work, that what’s the worst that can happen is it just doesn’t work. Most people, people find their own work to be precious in some way, and they hang on to it really hard. You have a very good attitude about it.

David Stenn: I’m lucky. I think I have some neurochemical, like, aberration, where if someone hates something I’ve done that I like, I can say, no, I like that. Whereas if someone loves something I’ve done that I don’t like, I’ll say no, I still don’t like it. I’m sort of my own harshest judge. But I have an ability that I learned early because I saw people like you’re saying, I saw writers torturing themselves over scripts or just beating their heads against the wall, and I thought, I have to be able to develop the ability to get to a certain point and say, this is the best I can do, and let go.

Steve Cuden: well, I think that that’s really wise. If you can let it go, that’s really helpful to having a longer career so that you don’t run yourself out of town.

David Stenn: Yes, probably that’s true, because I’ve had a long career so something allowed me to be able to do that.

Steve Cuden: How similar was your experience then in doing the Gene Harlow book?

David Stenn: The Jean Harlow book was a lot easier in one sense, which was I didn’t have to prove myself. So I had already this book that had been a surprise hit. And so people were much more willing to speak to me. With Clara Bowe, it was harder because I was a kid. I was unproven. When you have a book under your belt, I could send it to people and say, I remember Irene Mayer Selznick, the wife of David O. Selznick, ex wife and the daughter of Louis B. Mayer. She never gave interviews. And I sent her my book, and I sent a letter, and she called me and she said, no one’s ever sent anything to me that’s this organized, and I read your book, and I will talk to you. So that was a calling card that I was. I was. Was fortunate to have that the second time. and also the mission for me creatively was different, because with Clara Bow, I felt almost like a knight, you know, a can eyed ght who was there to rescue her from this really undeserved reputation. With Jean Harlow, I felt more like Woodward or Bernstein. Solving the mystery of her death and solving the mystery of her husband’s death. It became much more investigative, in a way, of, because there had been a lot written about Jean Harlow, and all of it was girless and false and fictitious. So I was able to sort of correct the historical record. And that felt more dispassionate, in a way. With Clara Bow, I was emotionally involved, in a way.

Steve Cuden: Were both of those outcomes fulfilling for you to get to that point?

David Stenn: They were different, and they were fulfilling for me, being someone who really relies on his emotions. The first one was like a love affair, and the second one was like a job, but it was a great job. And I think that would have been true if I’d done a third book with Jackie. I think I would have had a very different relationship with my subject as well.

Steve Cuden: You bring up Jackie again, and I think that that’s, also part of this. What was her contribution to this? How did she make these books?

David Stenn: Great. Well, thank you for saying that. Great. I mean, she was. People always obviously ask about her. I always say, think of the best thing you can think of, and it was better. Wow. She was such an amazing, extraordinary human being on so many levels. And she loved writers. Writers were her favorite people. How many people do you meet where writers are their favorite people?

Steve Cuden: Well, not too many.

David Stenn: And she told me, I think she put it, she always had an elegant way of putting things, a very, And she said, you know, I really would have gone into publishing if my life had been different.

Steve Cuden: Well, she did go into publishing, but.

David Stenn: I meant as a younger person.

Steve Cuden: She would have never gone into politics. She wouldn’t have met Jack Kennedy, all that.

David Stenn: She loved books. The first time I went to her apartment and. And I went into her library, and she came in and she gestured to the shelves of books, and she said, these are my friends.

Steve Cuden: Oh.

David Stenn: And I thought, I feel the same way. I didn’t know anyone else thought that my books are, my friends. And so I think both of us really were simpatico in that sense. But the greatest gift she gave me at first was just this implicit belief that I could do this because I was 25 by that point. I’d never written a book before. And she used to just offhandedly say, well, when the reviews come out, everyone will know. Or, well, when you see the sales figures, as if it was a given, that this book would get great reviews and sell. And so I believed her because I thought, well, she knows a whole lot more than I do, and she’s been around, so she knows this. I guess she’s right. And I just didn’t get frightened. I was able to work without being anxious or being nervous, and I could focus on what I was doing. And I think her belief in me, her confidence in me, her confidence about the book, her confidence that my subject was interesting, it was the greatest gift I could have been given, because it wasn’t obvious. It was just, like I said before, implicit.

Steve Cuden: I think it’s fascinating that you weren’t intimidated just meeting her in the first place.

David Stenn: Well, I felt like, this is my editor. I need an editor. I can’t be intimidated by a person I’m working with because that will impact my work. So if I can’t do that, then I shouldn’t be working with her. And I really wanted to work with her. So I thought, I have to really focus on Clara Bowe, not Jacqueline Onassis, of course. And I think also she loved that because she was a very humble person. So she loved the fact that it was a young person who didn’t remember her when she was first lady, was too young, and so could just treat her as an editor. And that’s what I did. I mean, it was very much of an editor writer kind of dynamic, which.

Steve Cuden: Is interesting to me, since you are an aficionado of people from the past. You’re a historian, you’re a documentarian. You absolutely have a fascination with things from 70, 80, 90 years ago, and here you are with a living piece of history in your face, and you were not intimidated by her.

David Stenn: Yes, although it’s true. Although, you know, I was writing about someone who was so historically important, and so that’s really where my focus was.

Steve Cuden: I think that’s great, and I think the listeners should pay attention to that because you were focused on the work, not on the ephemera, around the work.

David Stenn: That’s right. And because I was writing about somebody who had left her work as her legacy, as all artists do, I knew that the Life was only important if the work was there. And I always understood it’s always about the work. And that’s why so many difficult people that you work with, if their work is worthwhile, you forget how difficult they are. If you’re working with someone who’s difficult and you’re not, you know, impressed with the work, it’s very hard to work with them. And so I also realized really early on, I personally can’t work well with people I don’t respect. I really need to like the job I’m doing, because if I’m doing a job I don’t like, if I’m doing a money job or something, I won’t be good. Some people can do it, and I really admire them. I’m I can’t do it. I just. I’m not good.

Steve Cuden: That says a lot about you and your character. You understand yourself well enough to know that you cannot put up with that because it’s not palatable to you.

David Stenn: Well, I learned. I learned by, by doing or not doing, because I was on some big tv shows, and some of them I didn’t really like, and so they would keep giving me a raise as if that was going to make me happier. And I learned, no, I don’t need the money. I need to really feel proud of. I mean, I need money, but I don’t need the kind of. I was never in the business for that reason. Because if you really want to make, make money, there are a million, other businesses that are much better odds.

Steve Cuden: But if you can hit it in that business, you can make a lot of money. Jeff.

David Stenn: Well, when people are starting out, especially now, where the business is so difficult and they’re concerned, I always say, because I believe this, and I’ve always believed this, if you’re good, there’s room for you. They’re always looking for good people. They’re always looking for talent. Everybody reads a script hoping it’s good. Everybody goes into a casting meeting hoping this person is the right person. And you see so much talent, it’s very inspiring to be in. Like I said before about the writers room, when you’re in a room with people and you respect their work and some people, their story sense is so great, or some people just, they’re, so funny or they’re so smart. And I could name so many people I’ve worked with where I felt that way. And it’s just a pleasure to come into work every morning.

Steve Cuden: I exactly understand that sentiment. Let’s talk about someone who had the opposite, where they had no respect. Let’s talk about Patricia Douglas and girl 27, which started with, it happened one night at MGM. Tell us the brief on that story.

David Stenn: Well, that started. I was having lunch with Jackie and bombshell was about to come out and she was always trying to get me to do another. She would say, what are we doing next? What are we doing next? And when Jean Harlow died the first week of June in 1937, that was a huge story. I mean, this 26 year old, the biggest, MGM’s biggest female star is dying at the same time the Duke of Windsor is marrying Wallis Simpson. So you have two of the biggest stories of the decade. And this other story is pushing both those stories off the front pages. And it’s about this 20 year old dancer who claims she was called for a movie, a, musical, and it was actually she was tricked into attending an MGM stag party. And I’d never heard of it. And I saw myself as sort of the rain man of Hollywood lore. I could reel off things ever since I was seven and I’d never heard of this. And so I immediately thought, well, it’s probably not true because otherwise, why haven’t I never heard of it? So I called Bud Shulberg, who was the son of BP Schulberg, who ran paramount and then became a very important screenwriter who wrote on the waterfront and also a novelist who wrote what makes Sammy run. So he had lived it all and he had written his memoirs. And so I asked him about it and he said, and I’ve never heard of it either. But it was a common shakedown of some of these hungry starlets to say, oh, Mister Schwartzberg raped me. I want a contract. So I thought, well, he would know. But I started researching it and she wasn’t going away. She wasn’t settling for a contract. She wanted justice. She kept pursuing it in the courts. And then I got obsessed. And I mentioned that to Jackie, and I said, but we’ll never know what happened. How can you find out? And Jackie said, well, if anyone can find it, it’s you. And again, you have this endorsement by someone that you respect. And I thought, well, again, what can I do but fail? I mean, if I fail, I fail, but at least I’ve tried. So I started researching it, and it took me years, but I ended up finding Patricia Douglas, who had literally been in hiding for 66 years. And so that became a story that I wanted to tell immediately because she was old and in poor health, and I wanted vindication for her. So I didn’t want to write another book because it was too. I needed to do it immediately. Jackie had passed away already, which was, devastating for me. But I went to Vanity Fair, and I said, would you be interested in this StoryBeat? And they were. And so they published it. And Patricia, got to have that vindication in her own lifetime. And then after she had passed away, I thought, well, I had filmed her because I thought it’s almost like, you know, show a testimony by a Holocaust Survivor what she’d been through. And I wanted for the historical record for there to be film of her. She’d never granted an interview before that, even during all of this, you know, sensational events of 1937. So I decided to make a movie. And you were very gracious in calling me a director, but I just don’t think, like, setting up a camera and saying to your DP, okay, go is directing. So I did not take director credit on that movie.

Steve Cuden: You clearly have not seen enough movies, because, yes, there are many directors that just set up a camera and go.

David Stenn: Well, when girl 27 got into Sundance, they said, you know, they started listing me as director, and I said, oh, can you not do that? They said, no, of course we have to do that. You directed the movie. Like, we have to do that. So. But I really had no. Like I said before, I had no directorial aspirations, which was fortunate because I really don’t think I have any directorial.

Steve Cuden: Well, you didn’t direct actors in scenes, but as a documentarian, you were the person that directed where you’re gonna look, where you’re gonna place the camera, where you’re gonna do things that makes you a director.

David Stenn: Well, thank you. I felt that film was storytelling, and it was really a journey, my journey, into finding her and. And opening up this story and then my relationship with her, because I was fascinated by that. Because when you call someone up who has essentially not left their home in decades, and you say to them, a complete stranger, I know your deepest, darkest secret. You have an instant intimacy. And that relationship was fascinating to me because I was the first person, literally, who knew because everyone else had died, so I was the only one who knew besides her. And so the. The dynamic that developed between us was. Was extremely intense emotionally. And she, at a certain point, she said, you need to call me grandma.

Steve Cuden: Oh, wow. Really?

David Stenn: Yeah. She needed that feeling. She needed to feel like I was family, because she was entrusting me with the most traumatic experience of her Life.

Steve Cuden: And part of the movie is you actually trying to get her to do stuff on camera, to just talk to you on camera. Yeah.

David Stenn: it wasn’t easy. It was. I mean, she used to say to me when I first started calling her, you know, why don’t you leave me alone? I’m an old woman. Let me die in peace. And I would hang up the phone and think, oh, David, you monster. But then I would think, okay, in 1937, she would not give up. She wants justice. This is character, logical. She wants vindication. And she did. She just needed me to earn her trust.

Steve Cuden: And so you just kept digging?

David Stenn: Yes. I dropped everything. I mean, I literally sort of stepped back from my career and said, I need to do this, because I knew the clock was ticking. If she died, the story died with her.

Steve Cuden: So tell us the story then. What happened to her?

David Stenn: Well, she went to this party along with 120 other girls, most of whom were under age. They were dancers, and the party was a stag party. And she was raped. And they told her, take your $7.50 and be happy and go away, figuring she would never do anything because your career would be over, your reputation would be ruined. It was a culture that blamed the victim, and she went to the DA. And the DA, whose biggest campaign contributor had been Louis B. Mayer in his most recent election, sat on it and did nothing. So she went to the press, and then she ended up filing what became the first federal civil suit for rape in legal history. She made rape a civil rights case and had no idea she was doing it. She did not realize until I told her 60 years later that she had made history. And I’m really abbreviating the story. But MGM managed to shut it down, the entire thing, and so she dropped out of sight.

Steve Cuden: It shows the power that the studios had then, especially MGM, which was the 800 pound gorilla in Hollywood at the time, and they controlled the town totally.

David Stenn: I mean, Louis B. Mayer was the highest paid executive in America. He made more than the president of the United States, and MGM was the largest employer in La County. MGM M had their own police force, which was populated primarily by ex LAPD, and that was intentional. So she never stood a chance. And the fact she said to me, I knew it, but I had to do it. I had to make them stop having those parties. I thought she was heroic. And it was really important to me to get that story told. So it became perhaps my most personal project because I’ve never worked on anything before, and I don’t think I ever will again, where you’re actually changing someone’s life. And that’s what happened. Coming forward again, coming out with her story again and being vindicated before she passed away, it changed her life. It gave her pride in herself, because she had internalized all of these attitudes about rape victims being bad, dirty, all the things they were told back then. So the idea that she saw herself as an important figure, as a hero, I mean, she really was the Rosa park of rape culture. She was the Rosa parks of rape culture. She was the first person ever to do this.

Steve Cuden: Well, I think to a large degree, things have changed, and to a large degree, things have not changed. And we’re still in a culture where, unfortunately, I think sometimes rape victims are still not respected in that way.

David Stenn: Yes. And Hollywood was built, and it is the only industry that was built on the commodification of women. And so women in film have always been treated in an objectified manner. And that culture back then, you see these movies, and a lot of people who have seen girl 27 say to me, I’ll never watch an old movie the same way again, because you see the chorus girls in some of these musicals, and you realize, all right, this is a 14 year old, and look what she’s wearing. She’s wearing, or I should say, look what she’s not wearing because she’s wearing a lot less than someone in a video today, a music video. And so there were no. No sexual harassment standards at all, any kind of protections, employee protections. So a lot of the women I interviewed who worked at the time alongside Patricia Douglas, the word that came up the most for them is hunted. They felt hunted. One woman told me, I used to bring a book because men would stay away from a girl who was reading a book.

Steve Cuden: That’s crazy.

David Stenn: Yeah, but the underbelly underneath. I wasn’t trying to be a muckraker because I. I love those films for what they are. But I also felt like this is a part of history that has been completely suppressed, oppressed, repressed, and it needs.

Steve Cuden: To be told, do you have plans to try to sell it so it gets made into a narrative feature?

David Stenn: I haven’t. I don’t have plans to,

Steve Cuden: Or even a series. It’d make a great series, too.

David Stenn: Yeah. It’s a tough subject, but I think it would. It’s an amazing story because the fact that she lived to tell all those decades later and have the last word, she lost in the court of law, but she won in the court of history, and the court of history lasts a lot longer than the court of law.

Steve Cuden: And, you helped to do that.

David Stenn: I was the person who facilitated it, but I always felt like she was waiting, because after she. The article came out and I read it to her, she sighed and said, thank you. I can go now.

Steve Cuden: Oh, wow. That’s powerful.

David Stenn: Because, yeah, she could rest in peace. I really felt the first time, she allowed me to meet her in person, she was sitting on her couch, almost like Buddha, waiting. And I thought, she’s waiting. She really does not want to go before she’s found justice.

Steve Cuden: She was haunted.

David Stenn: Yeah. And a lot of other people that I interviewed, you know, and even at Sundance, after each screening, there would invariably be a couple of women, they were actresses or not, and who would come up to me and say, thank you for this film. And you could tell just by the way the exchange and the look that they had been through something.

Steve Cuden: Well, I, for one, hope that you can find a way, as a well known screenwriter, David, to turn this into some kind of a. Either a feature film or a. A limited series, because I think it’s a very important story. The way you’ve told the documentary is terrific, but I think it deserves a much broader audience. And you’re going to only get that through either through a book or through a big feature.

David Stenn: I have ideas.

Steve Cuden: Well, I hope you get there. I’ve been having the most fascinating conversation with David Stenn the screenwriter, author, documentarian for the last hour plus, and we’re going to wind the show down a little bit. And, in all of your experiences, and you certainly had many, are you able to share with us a story that’s either weird, quirky, offbeat, strange, or just plain funny? More than the ones you’ve already told us?

David Stenn: You know, there were so many that I don’t even know where to start.

Steve Cuden: Well, give us at least one.

David Stenn: I’ll share the first one because it always stuck with me. It shows what a sort of hayseed I was, which is the first Hill Street Blues episode I ever rode. They were shooting and the director was there, and everyone went in, and I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. So I stood outside on the lot while the door was shut and they were shooting inside, and Stephen Bochko was driving by in his golf cart. And he said, david, what are you doing out here? And I said, oh, well, they’re making the show and I’m waiting. And he said, well, what are you waiting for? I said, well, they’re working inside. He said, you wrote that show. Go in, get inside. And I also remember working on Beverly Hills, 90210, and in those days, you didn’t know if your show was working or not until the ratings came in. And even then, we were on Fox, which was a nascent network, so all those ratings were low anyway, so we couldn’t tell. And I remember on a Monday morning, my assistant showed up and she said, luke Perry went to a mall in Florida this weekend, and 18,000 kids showed up. And I said, but that’s not possible. 18,000 people don’t watch our show. So you could really be the last to know that you had this massive hit on your hand.

Steve Cuden: You had more than 18,000 people watching that show.

David Stenn: Well, that’s how we found that out.

Steve Cuden: And became even bigger after that.

David Stenn: Yes, by that point, we had figured it out. But I remember that was the moment where I thought, this show might.

Steve Cuden: Be working and continue to work for quite some time. So our last question for you today, David, and you’ve shared with us a whole lot of information today. That’s very, very useful advice for anyone who’s in the business. But I’m wondering, do you have a solid piece of advice that you can share for those who are just starting out in the business, not quite like you did, perhaps, but starting out in the business, or maybe they’re in a little bit and trying to get to the next level. And that can be for either writing books or for the business of Hollywood.

David Stenn: Well, what I would like to share does cover both. And it was told to me by my very first mentor, William Goldman, who I met when I was in college, because I would write everyone a letter. I didn’t know them, but I would write them all letters. And I wrote him a letter because I admired him so much. By that point, of course, he had won two oscars, one for Butch casting the Sundance kid, one for all the president’s men. He was an extremely successful novelist who had written magic and marathon man, and he’d written non fiction books about Hollywood, which became sort of adventures in the screen trade, which became sort of a bible of, of how to handle yourself in the business. And he said to me, well, if you’re ever in New York, look me up. So of course I said immediately, I’ll be there next weekend, which I had no plans to, but I got there, and that was the first time I met him and I got to know him, and he was wonderful to me, and he was wonderful to a lot of people. But one thing he said to me that I never forgot, and not only didn’t I forget it, but I lived by it, which is, don’t just do this. And I said, but what do you mean? That’s all I want to do. And he said, no, you have to find something else to do. I write books because when they break my heart over a script, I have my books because my books belong to me. And I thought, huh? And you were asking me earlier why I moved to books when I was doing so well in television. And that’s why. Because I remember thinking, okay, I’m doing this now and I’m doing well, but I need to be doing something else because Bill told me I should really be also having some parallel thing, that when they break my heart will be unbreakable, heartwise. And that was the advice that I’ve lived by my entire career.

Steve Cuden: Well, first of all, William Goldman is arguably my number one, maybe my number two, one, two greatest screenwriters ever, favorite movies of all time, he wrote, including the Princess Bride.

David Stenn: Yes, the Princess Bride and the book.

Steve Cuden: Of the Princess Bride. First, he was an exceptional human being in any kind of literary arts. And very curiously, also in movies, which are not thought of as literary arts at all. And so that’s very, very wise advice, that you should have something else. And it doesn’t necessarily mean it has to be something else in writing or the arts or whatever you’re doing, it can be something else outside of it.

David Stenn: That’s right. So when they hurt you and demean you or humiliate you or just treat you generally badly, which writers, I think they hate us because they need us.

Steve Cuden: Well, that may be.

David Stenn: And so we are mistreated, in a way, in terms of our work, that directors and actors and cinematographers and everyone else aren’t, because we’re the authors, but they’re telling us right from the start, no, you’re not.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s because of that whole business of you don’t retain your copyright, and when you don’t retain your copyright, they don’t respect you at all.

David Stenn: That’s right.

Steve Cuden: Because in New York, the playwrights are respected.

David Stenn: That’s right. And yet they need you. Because actors need a script. Directors need a script. So the fact that they need you lately, currently, the big issue is, will AI replace us? I personally don’t believe AI can replace a beating heart, but if it could, they will be very happy because they can eliminate the writer.

Steve Cuden: Well, let’s hope that that never happens, because I, think that it is a human enterprise to write and create and to create art in particular, since.

David Stenn: The cave paintings at Lascaux, you know, people want pictures with stories.

Steve Cuden: Absolutely. David Stenn. This has been so much fun for me. Really great storytelling in your life and all of these wonderful books that you’ve written, especially Clara Bow, especially Jean Harlow or bombshell, and also girl 27, I think these are great contributions. And so I thank you kindly for your time, your energy, and your wisdom today, for all the wonderful things you’ve done and said.

David Stenn: Thank you so much. I had a great time.

Steve Cuden: and so we’ve come to the end of today’s StoryBeat beat. If you like this episode, won’t you please take a moment to give us a comment, rating, or review on whatever app or platform you’re listening to? Your support helps us bring more great StoryBeat beat episodes to you. StoryBeat, beat is available on all major podcasts, apps, and platforms, including Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, iHeartradio, Tunein, and many others. Until next time, I’m Steve Cuden, and may all your stories be unforgettable.

0 Comments