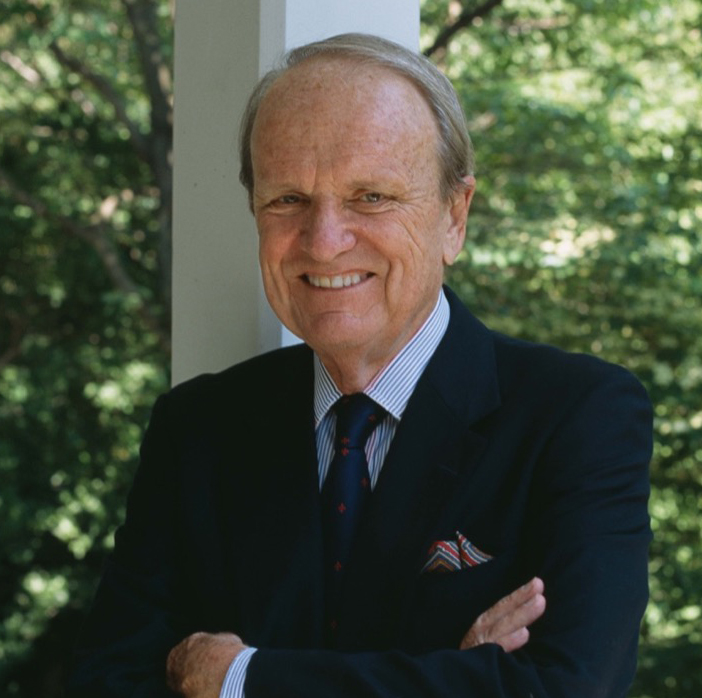

For our 250th Episode, we have one of the all time greats in movies, TV, and theater! George Stevens, Jr. has crafted an extraordinary creative legacy over a career spanning more than 60 years as a screenwriter, director, producer, playwright and author. He’s enriched the film and television arts as a filmmaker and is widely credited with bringing style and taste to the high-profile, national television events that he has conceived. In doing so he’s lived one of the most profoundly influential American lives ever.

As a writer, director and producer, George has earned many accolades, including 15 Emmys, two Peabody Awards, the Humanitas Prize and 8 awards from the Writers Guild of America, including the Paul Selvin Award for writing that embodies civil rights and liberties. In 2012, George received an Honorary Academy Award for “extraordinary distinction in lifetime achievement.”

George served for eight years as Co-chairman of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities following his appointment by President Obama in 2009.

He’s the Founding Director of the American Film Institute. During his tenure, more than 10,000 irreplaceable American films were preserved and catalogued for future generations. He also established the AFI’s Center for Advanced Film Studies, which gained a reputation as the finest learning opportunity for young filmmakers.

With Nick Vanoff, George created the annually televised Kennedy Center Awards in 1978, which he wrote and produced for more than 35 years.

George executive produced Terrence Malick’s film, The Thin Red Line, which was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture. He co-wrote and produced The Murder of Mary Phagan, starring Jack Lemmon, which received the Emmy for Outstanding Mini-Series. He wrote and directed Separate But Equal starring Sidney Poitier and Burt Lancaster which also won the Emmy for Outstanding Mini-Series. He produced two acclaimed films about his highly revered, Oscar-winning father, George Stevens: A Filmmaker’s Journey and George Stevens: D-Day to Berlin. In collaboration with his son and partner, Michael Stevens, he produced the feature length documentary Herblock – The Black & The White on the famed political cartoonist Herbert Block.

In 2008, George made his Broadway playwriting debut with Thurgood, starring Tony nominee Laurence Fishburne as Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

As an author, George has published: Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age, and Conversations with the Great Moviemakers – The Next Generation, featuring interviews with notable filmmakers from the AFI’s Harold Lloyd Master Seminar Series. In 2022 he published his autobiography, My Place in the Sun. I’ve read My Place in the Sun and can tell you it’s a truly entertaining memoir of his family’s show business legacy as well as his own top-tier life in Washington, Hollywood and beyond. I highly recommend this most excellent book to you.

WEBSITES:

BOOKS BY GEORGE STEVENS, JR.

IF YOU LIKE THIS EPISODE, YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY:

- Sheldon Epps, Director-Producer-Author-Episode #248

- David Carpenter, CEO of Gamiotics-Producer-Episode #235

- Amanda Raymond, Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #222

- Charlie Peters, Writer-Director-Episode #221

- Karen Leigh Hopkins, Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #207

- Chris Moore, Movie and TV Producer-Session 3-Episode #195

- Adam Weinstock, Producer-Director-Actor-Episode #181

- Jamie deRoy, Tony Award-Winning Broadway Producer-Episode #143

- Bryan Cranston, Legendary Actor-Producer-Writer-Director-Episode #132

- Vicangelo Bulluck, Writer-Director-Producer-Episode #116

- Bill Isler, Producer of Mister Rogers Neighborhood-Episode #107

- Hawk Koch, Legendary Movie Producer-Episode #101

- Andy Tennant, Screenwriter-Director, Episode #92

- Tamara Tunie, Actress-Director-Producer-Episode #68

- Norman Steinberg, Screenwriter-Producer-Director-Episode #27

- Ken Davenport, Playwright-Broadway Producer-Episode #4

Steve Cuden: On today’s StoryBeat…

George Stevens: Dad was assigned by General Eisenhower to organize the film coverage of D-Day and The War in Europe. He had set up a special unit, the Special Coverage Unit, which became known as the Stevens Irregulars. Dad went in on D-Day, did Juno Beach on the HMS Belfast that fired the first shot for the flagship, the greatest seaborne invasion in history, and rode across Europe in a Jeep with a pistol on his hip and a carbine between his legs. From Normandy through Paris, through the Battle of the Bulge, and to the Dachau Concentration Camp where he ceased being a cover of history in his own mind, became a gatherer of evidence, filming what was there so no one could ever say it didn’t happen.

Narrator: This is StoryBeat with Steve Cuden, a podcast for the creative mind. StoryBeat explores how masters of creativity develop and produce brilliant works that people everywhere love and admire. So join us as we discover how talented creators find success in the worlds of imagination and entertainment. Here now is your host, Steve Cuden.

Steve Cuden: Thanks for joining us on StoryBeat. We’re coming to you from the Steel City, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Well, we have a very special show today. My guest, George Stevens Jr., has crafted an extraordinary creative legacy over a career spanning more than 60 years. As a screenwriter, director, producer, playwright, and author, he’s enriched the film and television arts as a filmmaker and is widely credited with bringing style and taste to the high-profile national television events that he’s conceived. In doing so, he’s lived one of the most profoundly influential American lives ever. As a writer, director, and producer, George has earned many accolades, including 15 Emmys, two Peabody Awards, the Humanitas Prize, and eight awards from the Writer’s Guild of America, including the Paul Sullivan Award for writing that embodies civil rights and liberties.

In 2012, George received an Honorary Academy Award for extraordinary distinction in lifetime achievement. George served for eight years as co-chairman of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities following his appointment by President Obama in 2009. He’s the founding Director of the American Film Institute. During his tenure, more than 10,000 irreplaceable American films were preserved and cataloged for future generations. He’s also established the AFI Center for Advanced Film Studies, which gained a reputation as the finest learning opportunity for young filmmakers.

With Nick Vanoff, George created the annually televised Kennedy Center Awards in 1978, which he then wrote and produced for more than 35 years. George executive produced Terrence Malik’s film, the Thin Red Line, which was nominated for Seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture. He co-wrote and produced The Murder of Mary Fagan, starring Jack Lemon, which received the Emmy for outstanding miniseries. He wrote and directed Separate But Equal starring Sidney Poitier and Burt Lancaster, which also won the Emmy for outstanding miniseries. He produced two acclaimed films about his highly revered Oscar winning father, George Stevens, a Filmmaker’s Journey, and George Steven’s D-Day to Berlin.

In collaboration with his son and partner Michael Stevens, he produced the feature length documentary Her Block, the Black and the White on the famed political cartoonist Herbert Block. In 2008, George made his Broadway playwriting debut with Thurgood starring Tony nominee Lawrence Fishburne as Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. As an author, George has published conversations with the great movie makers of Hollywood’s golden age and conversations with the great movie makers of the next generation featuring interviews with notable filmmakers from the AFI’s Harold Lloyd Master Seminar series.

In 2022, he published his autobiography, My Place in the Sun. I’ve read My Place in the Sun and can tell you it’s a truly entertaining memoir of his family’s show business legacy, as well as his own top-tier life in Washington, Hollywood and beyond. I highly recommend this most excellent book to you. So for all those reasons and many more, I am deeply honored to have the extraordinarily multi-talented and highly influential writer, producer, director George Stevens Jr. join me today. George, welcome to StoryBeat.

George Stevens: Listening to all that, I’m exhausted. Anyway, thank you for that.

Steve Cuden: It’s a big life and your book shows that you have lived a big life and it’s very, very intriguing, and impressive. So let’s go back in time a little bit. You come from a substantial lineage of show business artists. Your grandmother, Alice Howell, starred in dozens of silent films. Your mom was in a few too. Your father’s parents were longtime stage veterans as well as they worked in the movies as well. How old were you when you first understood that the family business was entertaining others?

George Stevens A wonderful question, but we must add that my great grandmother, Georgia Woodthorpe, born just after the Civil War in San Francisco became a great actress on the stage. She is famous for being the youngest Ophelia to the great Edwin Booth’s Hamlet.

Steve Cuden: That’s right.

George Stevens: Shakespeare actor. So she started five generations of show business. I guess as a little boy, I knew this stuff was going on, but my grandparents were no longer on the stage in San Francisco, and I kind of knew they were acting in movies. My grandmother, Alice Howell, made over a hundred silent films, the first five of which were directed by Charlie Chaplin. She was just a nice lady. My grandmother who lived across the way and brought us casseroles. I kind of knew she was an actress, but as we now say, I wasn’t into it.

Steve Cuden: Did she not pass along any history or business information to you?

George Stevens: She never talked about it. She was open and all of that, but she’d done that, and she’d moved on in her life.

Steve Cuden: She’s the opposite of a braggart.

George Stevens: Indeed. Yeah.

Steve Cuden: Was show business fascinating to you early on, or did it take a while for you to glom onto it?

George Stevens: It was interesting to me, but I was certainly not preoccupied. I was much more interested in the Hollywood Stars Pacific Coast League baseball team. When I was about, I guess nine or 10, I discovered that dad had a 16-millimeter projector and his films up till that point were there. I used to thread it up and run Wheeler and Woolsey comedies until my favorite came along about, I think, well, I would’ve been nine or 10 called Gunga Din, the great outdoor picture with Cary Grant and Douglas Fairbanks. One of the great action-adventure pictures. So filled with humor and humanity.

Steve Cuden: So he started as a cameraman for Hal Roach, and he was doing Laurel and Hardy comedies early in his career. Correct?

George Stevens: He started at 24 photographing and being a gag man on the Great Laurel and Hardy comedies. It was during that time that he got this idea that comedy could be graceful and human. That it wasn’t all about the guy falling in the cement drawer. You see that in his films as he goes through life that humor is graceful and human.

Steve Cuden: I’m very impressed that Gunga Din, which really at its core is not a comedy, but it has a lot of comedy in it.

George Stevens: It’s just so funny. Yeah. Wonderful Cary Grant. Just the situations are funny, and Dad knew how to make them part of the story without distracting from the drama.

Steve Cuden: It was part of the storytelling. He obviously had serious range. He made comedies. He made dramas, even musicals. He made Swing Time. Do you think that’s what kept him fresh? That he kept moving from genre to genre?

George Stevens: I think that he was always looking for something new. He never wanted to jump out of the same hole twice.

Steve Cuden: Yeah. Who can blame him? I mean, he obviously was very influential on many different kinds of movies as opposed to many directors today that sort of get into a pocket and whatever hole that they’re in, that’s what they are known for. Your father again, he said that you quote it in your book that I left comedy, but Laurel and Hardy never left me. So do you think that that early work is what then sustained him because he learned comedy first?

George Stevens: Certainly when you see his later films. We had showed the restoration of Giant last year at the Turner Classic Film Festival. Steven Spielberg and I introduced it because Steven had suggested that we do a 4K restoration and in the thousand seat Groman’s Chinese Theater, where the film had premiered 65 years earlier. To see it with an audience 65 years later in the same theater. Now it’s IMAX with an even bigger screen. How the audience related to that and how the themes of the independent woman. The treatment of the Hispanics. Just all things that are so in our lives today. But it’s so much laughter in this drama of three hours and 20 minutes that there are these scenes where there’s just either quiet humor or sometimes really out loud, big laughter humor.

Steve Cuden: The thing that I’m impressed by is how it wasn’t glib. It could have been easily glib, but it was just part of those characters and it worked perfectly.

George Stevens: He never was fond of that phrase screwball comedy because he felt that was people acting funny and he wanted the humor to come out of character and situation.

Steve Cuden: So aside from your father, who would you say has most influenced the way you think and approach creative problem solving and creativity? I assume your father was a huge influence on you, but who else?

George Stevens: Well, he was certainly in that practical sense. I just was around, and I just learned so much from him. But I respond to the work of David Lean of Lawrence of Arabia, Dr Zhivago just for the sensibility and the mastery of scale and drama and Truffaut and Fellini. There’re just so many that you learn from.

Steve Cuden: You’ve had the great good fortune to actually interact with any number of those people one-on-one, haven’t you?

George Stevens: Right. First we did the AFI Life Achievement Award where we started with John Ford and James Cagney, and Lillian Gish and Betty Davis and John Houston and Frank Capra, Billy Wilder and Orson Welles and blah, blah, blah. Then we did the seminars at AFI and my book the AFI Seminars in the Golden Age of Hollywood, starting with Harold Lloyd and with Fellini and Rosselini and all the Great American directors. To tell you a story that your audience might enjoy, it was 1952, and I went to the Academy Awards with my father. He’d been away at war for three years in combat, and he’d made one film, and then he just finished in his next film. We went to the Oscars, and it was nominated. Joseph El Menowitz, who was president of the Director’s Guild, came out to present the award. Menowitz had made All About Eve and won the Oscar the year before. He read the nominees. John Houston for the African Queen, William Weiler for Detective Story, Vincent Minnelli, an American in Paris, Elia Kazan, a Streetcar Named Desire, and George Stevens a Place in the Sun. Such a list. Right?

Steve Cuden: Extraordinary.

George Stevens: Driving home that night, the Oscar was on the seat between us. He was driving the car, and he looked over at me and he said, we’ll have a better idea what kind of a film this is in about 25 years. On his big night, his first Oscar. That’s what he was thinking. He’d grown up in the theater and he knew that with plays, it’s the test of time. Now he did not know that the 18-year-old sitting alongside of him would one day be the founder of the American Film Institute, which is kind of based on the test of time. Films that last. Preserving the films that last. Training the filmmakers who will make films that last. I didn’t think about it at the time, but I realized much later that that one moment with him created an idea that stuck in my head or heart somewhere.

Steve Cuden: When I was at UCLA, one of my teachers was Professor Howard Suber. Howard used to talk about that the way that a movie becomes part of the fabric of the world is that it has to be memorable and popular over at least 10 years or more. Then when it’s memorable and popular over 10 years or more, it then becomes truly something that’s in the fabric.

George Stevens: Yeah. The picture he was referring to that night in 1952, 1952, A place in the Sun is now 70 odd years old.

Steve Cuden: Crazy.

George Stevens: When Mike Nichols was asked how coming from the theater having never really been on a sound stage, how he could go out and direct Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf for his first movie and make it so superior? He said I watched A Place in the Sun 150 times.

Steve Cuden: Oh, Wow. Wow. That’s a good training round, isn’t it?

George Stevens: It is. Everything you need to know if you had no other way of learning anything you watch that film.

Steve Cuden: Orson Welles’ famously said that when he went to make Citizen Kane, he watched Stagecoach 40 or 50 times. So, I mean, obviously one movie maker influences another movie maker. Which leads me to the question about your father starting so early in the industry. He was around with DW Griffith and folks like that, and they were making it up as they were going along. Nobody had made movies before them. How did they do that? How did they figure out what we now think of as Hollywood?

George Stevens: Well, they had stories to tell, and you figure it out. I know you’re interested in the creative process, and it occurred to me, I remember going on the set of A Place in the Sun when I was in college on a Saturday. They used to film six days a week. Elizabeth Taylor, then 18—I was also 18—and Montgomery Cliff, extraordinary actor in kind of his third role, I think, on the screen. But they were both stars. They came on the set, and they were just starting a new scene. I saw my father talk to them. He said, well, Marty, why don’t you go in and why don’t you stand by the pool table and figure out something. Elizabeth, why don’t you start at the door, and you come in. They went and they did this scene. The script clerk would give them lines if they faltered. Then he said, well, all right. He said, well, why don’t we do it another time here. Just go ahead and do it again. They went and they did it again. Then he said, okay, well that’s nice. Let’s just do it one more time. You’re finding your way here. They went and they did it again. Then after that, Monty kind of came over and took him aside and started asking him questions. Then Elizabeth came over and so then they had a conversation and dad started telling him what he wanted them to do. Later I asked him. I said, dad, why did you just three go times without giving them any instruction? He says, sometimes for actors, it’s helpful for them to know that they might need a little help. But when they finally ask for advice, then they’re ready to listen.

Steve Cuden: I think of great directors, and many other people agree with me that great directors are also great psychologists. You have to be able to get into the headspace of both the technicians and the actors and everybody on the set as to what their particular human problems or difficulties or challenges are, and you have to help them overcome those. Am I correct?

George Stevens: You are. You’re right on.

Steve Cuden: Well, that is, and obviously your father was really good at it. Did he get that from his parents, or did he get it from working on early Laurel and Hardy movies?

George Stevens: Well, I’m sure of just a lifetime of when he was working with his father in San Francisco. Landers Stevens played with his wife Georgie Cooper. Landers was the actor manager in theaters in San Francisco. I think Landers played 500 characters. Leading roles. They were not wealthy. So the father and his brother used to be at the theater at night doing their homework. I found a recording interview he did once talking about that. He said, the time I really looked forward to was when my father was playing Sydney Carton in a Tale of Two Cities. I’d wait, and I knew when the end of the play was coming along, and I’d put close my books and I’d go sit under the stage. I’d hear my father walk, and I’d hear him climb up the steps of the guillotine and I’d feel the audience out there in the dark. He’d say, it’s a far, far better thing I do than I’ve done before. It’s a far better place I go to than… Then I’d hear the sound of the guillotine come down and hear the audience. Just the stillness of it. Then I’d hear the curtain unfurl and the board hit the stairs or the floor. Then all at once, I’d hear all these hands come together and applaud and cheer. You saw a child’s imagination in the dark hearing how an audience responds. So I think it started there for him.

Steve Cuden: He got it that there was a connection between the performers and the audience, and that was what was key.

George Stevens: Exactly.

Steve Cuden: So I have to ask about his experiences in World War II before we move on to other subjects. He made documentaries for the US government in World War II, correct?

George Stevens: Well, not exactly. Frank Capra made documentaries back here at home. Dad was assigned by General Eisenhower to organize the film coverage of D-Day and The War in Europe. He had set up a special unit, the Special Coverage Unit, which became known as the Stevens Irregulars. Dad went in on D-Day, did Juno Beach on the HMS Belfast, that fired the first shot for the flagship, the greatest seaborne invasion in history, and rode across Europe in a Jeep with a pistol on his hip and a carbine between his legs. From Normandy through Paris, through the Battle of the Bulge, and to the Dachau concentration camp where he ceased being a cover of history in his own mind, became a gatherer of evidence filming what was there so no one could ever say it didn’t happen. So he was away for three years. He said he saw men at their best. He had a 50-yard line seat and saw men at their best and their worst.

Steve Cuden: I’m wondering about his experiences throughout the war, and especially then seeing that kind of inhumanity. How do you think that that impacted his creative life after?

George Stevens: It became part of him. Yes. His subjects became deeper. Shane, A Place in the Sun, Giant, the Diary of Anne Frank, The Greatest Story Ever Told. So yes, it changed him. He maintained his humor. He did not become a different person, but he had seen things that affected him.

Steve Cuden: I imagine it powerfully affected him. It is amazing that he kept his sense of humor. A lot of people going through those experiences lose their sense of humor. So I think that that’s phenomenal. You also quote in the book of him saying that life is a journey and it’s most interesting when you’re not sure where you’re going. Talk about not sure where you’re going when you’re in the middle of a war. So what do you say to those who you meet that are up and coming filmmakers that may be uncomfortable with that unknown of where their future is? What kind of things do you say to folks like that?

George Stevens: Well, I say keep your eyes and ears open. If you’re at the AFI, sop up every bit of information that’s around. Also, believe in yourself. You may have to knock on a lot of doors, but you will get there. I’ve worked with my dad on Giant. Actually, I worked with him on the screenplay. I was with him and the two writers for nine months because my commission into the Air Force was delayed after college. I went in the Air Force for two years, visited the set many times, and got out in time to spend the last six months of the editing process with him, because it was a picture that took a long time. I was by then 23, and it was hot summer days in Los Angeles. We were there from eight in the morning till seven at night, and six days a week, sometimes seven. We previewed the picture, and God, it was clear that this is a wonderful motion picture. One day I said to dad, God, dad, this picture is really good. Why don’t you just lock it up and put it out there? He said, well, do you ever think about how many—he would’ve said today, man and women hours are going to be spent watching this picture? I thought about that for a moment. Then he said, don’t you think it’s better that we spend a little more of our time making it as good as it can be for those people?

Steve Cuden: What a great philosophy and way to look at it. Yeah, you spend a little more time and then, what does it do? It goes off and lasts for 70 plus years and on into infinity.

George Stevens: I must say, it has been one of the most successful kind. It kind of was inside me. This book. I finished it during Covid. But I would go over it and over it again and sharpen it and change it and trim it and trim it. Now I am so happy with the book and so happy with the response that people had. That response would not be as good if I had stopped three months earlier and said, this is—because people were saying, God, this is really good. The publisher was saying, God, you don’t want to go crazy. I wanted to go crazy. I wanted to just make it as good as it can be.

Steve Cuden: How many drafts do you think you did of that book? How many times did you work on it? How many different ways?

George Stevens: Because you work in a chapter, and you do that over and over. Then you put it together. Then you come back to it later and it’s the process. Creative people know it, and architects and composers. Lenny Bernstein wanted to get it right. Jerome Robbins with his ballets. I watched him and there was not too much work that could be done to get it up to the level that he wanted it to be.

Steve Cuden: Well, I’ve said more than once on this show, that Fred Astaire, who your father obviously worked with, made everything look effortless, but it took hundreds and hundreds of hours of him beating himself up to get it to look effortless.

George Stevens: Absolutely.

Steve Cuden: I will say, and I’m not just blowing smoke here, your book reads effortlessly. It is a wonderful, entertaining read. I’ve read lots of books about Hollywood. So you did the right thing by spending a little more time on it. You also write in the book that ambitious ideas invariably have a chicken and egg factor where several elements are required, and each depends on the other. What’s the best way to look at any chicken or egg situation?

George Stevens: Well, an example, the Kennedy Center Honors. That was an idea I had, and your audience may be familiar. That’s where we at the Kennedy Center have honored the great figures in the performing arts which became a hugely successful television show.

Steve Cuden: I watch it every year.

George Stevens: So I had that idea, and I’ll just tell you, interestingly, as you are interested in the creative process. An unrelated person named Roger Stevens was the chairman of the Kennedy Center. We had done in 1977, the 10th anniversary of the AFI. The big show in the Opera House of the Kennedy Center had a White House reception that the Carters gave beforehand. It was very popular on CBS. I went down to Roger Stevens the next day to thank him for giving us the Opera House for this successful event, and then said to him, you should really have your own event and television show to raise money and to serve a good purpose. He spoke funny. He said, do you have any ideas? I said, I have an idea. I said, it’s very simple.

I said, it’s carved in the wall of the building here, words of John F. Kennedy. I look forward to an America that will not be afraid of grace and beauty that will reward achievement in the arts, the way we reward achievement in business or state craft. John Kennedy had said that in a speech at Amherst College in honor of Robert Frost. It is basically the idea of the Kennedy Center Honors. So I had that idea. Then, what do you need? Roger Steven said, yes, I need a television network and I need the White House to say that it will have a reception because the president’s presence and a White House reception would draw the artists. You needed those three and they had to come together at the same time, along with a date in the Opera House.

So it was four things. We have the idea, Roger Stevens says, you’re going to have the Opera House. The first week in December of 1978, I talked to my friend Jerry Rafshoon at the Carter White House. I’m talking to CBS trying to sell them on this idea that you can really have opera and ballet on primetime television along with a lot of other good stuff. So you have to have all of those things come together and everybody say yes at once. So that’s chicken and several eggs.

Steve Cuden: You have to be, I guess, a little bit in the right place at the right time to have that happen. I just want to review. You didn’t get to that point just overnight. It took you a while to get to the position in life where people respected what you had to say in order to achieve that. So let’s go back and talk about your early experiences with Edward R. Murrow and the US Information Agency. How old were you when you started to work for Edward R. Murrow?

George Stevens: Well, I think I’ll give you just some transitional background that I was working in Hollywood after Giant, and I’d worked with Jack Webb of Dragnet. Jack made me a director at age 25. I went on to direct Peter Gunn and Alfred Hitchcock Presents. I wasn’t a full-time director because I was working with my father on the Diary of Ann Frank and pursuing projects of my own. When we finished the Diary of Ann Frank, Kennedy was elected in 1961, inaugurated, and he asked Edward R. Murrow to head the United States Information Agency, which told America’s story abroad with the Voice of America making movies. Edward R. Murrow and I did not know one another, but we met when he came to Hollywood. He asked to see me on a Sunday afternoon. I went up to Sam Gold Wind’s house and met with Ed Murrow while the famous croquet game was going on in the Goldwyn lawn.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

George Stevens: Edward R. Murrow asked me at 29 to come back and had the motion picture division of USIA. Parenthetically, I told him I couldn’t because I was at work with my father on The Greatest Story Ever Told. This is a father story. I didn’t feel I could abandon him. I was walking to lunch with my father on the Fox lot, and he had not heard about this, and it came up. He stopped walking and he looked at me and he said, I think you may have to do it. He was a father who understood that a son might flower in another atmosphere or that I should pursue my own dreams. So I did it and to work with Edward R. Murrow, who’s a person of such integrity, and John Kennedy. I was enamored of John Kennedy’s use of language, and he used to quote the ancient Greeks. There’s a wonderful book about Greek sayings. One of them was the ancient Greek definition of happiness, which he spoke of as the fullest use of one’s powers along lines of excellence. I wrote it down and then I realized here I was at my age making 300 documentaries a year with young filmmakers in this new frontier atmosphere. I realized that Ed Murrow and John Kennedy had given me that definition of happiness.

Steve Cuden: Amazing.

George Stevens: The full use of my powers. Both Kennedy and Murrow were inspirations. Kennedy was always talking about reaching higher and excellence and quality. Murrow was a man of such integrity. That just kind of became part of me. That’s what I wanted to do.

Steve Cuden: The USIA work that you did was making mostly short movies about one thing or another, right?

George Stevens: Yeah. The March on Washington. Martin Luther King to show that abroad. How we address civil rights. Later we made a movie called John F. Kennedy, Years of Lightning, Days of Drums after his death. There was a feature length film that in the framework of the funerals, the color footage of all of it, which we shot. We told the story of the new frontier. So lots of different kinds of documentaries.

Steve Cuden: About how many movies do you think you made in your time there? Hundreds?

George Stevens: Thousand.

Steve Cuden: A thousand. That’s a lot of movies. Where did you come up with all the ideas? How did you develop those ideas? Where’d they come from?

George Stevens: USI was a big organization. We had lots of people from different areas of the world responsible. They needed a film about this, and they flowed. It came. Some of them were regular weekly projects and just a lot of stuff.

Steve Cuden: So you’re now in Washington at this point, and you’re living in Washington and you’re working with the government, more or less. You’re not in Hollywood anymore. Though you’re doing something that they do in Hollywood, that’s making movies. Did you at that point already have some kind of a good grasp on how to be political in that environment?

George Stevens: Yeah. I’ve had no experience in that world but being around my father and seeing how he dealt with studio heads and how he dealt with big camera crews, I think, I learned. I never heard my father raise his voice in instructing anybody unless he had a bullhorn to talk to 400 extras. How he quietly had his way. I found that worked for me. Somebody asked me a variation of this question. Dad had been at RKO and then he went to Columbia in 1940 where Harry Cohen was notorious. He was abusive to directors, to everybody. Harry Cohen said, I want you to come here. I’ll never come on your set. You’re going to have final cut. Somebody said, well, how about dealing with Lyndon Johnson? I said, well, I guess if I’ve watched my father deal with Harry Cohen.

Steve Cuden: Well, do you think that the politics of Washington, which are obviously grand politics, are they similar in the way that artists must think about their creative lives in Hollywood? That there’s a political aspect to it as well? Or is it something they should not even worry about or ever think about?

George Stevens: Well. No, you have to think about it because you have to think about, if you’re going to do something in Hollywood, you’re going to have to spend a lot of somebody else’s money. That becomes a political question. How do you persuade them and gain control, hopefully, so you control the end product. That’s what I learned from my father. I exercised that idea that he wanted to control his movies not have somebody come and edit it at the end or tell him how to cast it. Which very much my state of mind when I was at USIA. I used to tell the story when Frank Capra was in the military. Colonel Frank Capra. During the war, my father’s friend and colleague, he was based in Hollywood, but he came back to the Pentagon to meet with the generals. Capra, who stood about five seven, was there in his colonel’s uniform. He comes into this room and there are 14 generals in a big conference table. They all go around and shake hands. Capra was very personable. Then finally he said, all right fellas. He said, we’re going to talk about movies, and they all nodded. He looked at the big, long conference table, he says, then I sit at the head of the table.

Steve Cuden: He was not going to not be the director of that meeting, was he?

George Stevens: No. Because everybody thinks they know how to make a movie. Frank knew that he had to stake out his territory. It didn’t matter how many stars they had on their shoulders. If they wanted him there, he was going to be in charge. So anyway, those are little, maybe bold stories. But it’s the way you have to think about it.

Steve Cuden: I think if you’re going to be a director on a big budget movie, you’d better be in charge of something because otherwise nobody’s going to pay you any mind, are they?

George Stevens: Exactly.

Steve Cuden: You have also interacted at the highest levels of the government of this country. You’ve interacted with presidents, with congresspeople, with senators and so on, and you have worked with both sides of the aisle. You’ve been good at dealing with both sides of the aisle. What do you think the secret is for getting people who disagree with you, philosophically and politically, to see what you’re trying to accomplish? What is the secret to that? Or is there a secret?

George Stevens: The case of the Kennedy Center Honors, it started with Jimmy Carter, and I had persuaded them and they were very enthusiastic. He was there for three years. The first two honors. Then Reagan was elected. So in comes a new president, and I’ve got all the people I work with, and I pointed out to them. I said, nowhere in the Constitution does it say that the president has to show up at the Kennedy Center Honors. I was kind of known as a Democrat. I didn’t know if that was going to stand me in a lot of favor with the new Republican president. So it was a matter of presenting it to them in a way and it was in a way, a natural, because Ronald Reagan was born to preside at the Kennedy Center Honors.

Steve Cuden: Of course.

George Stevens: Once they agreed to do it, I found it very easy to work with them. You had to tread carefully and make sure that they knew they were respected, and they had a voice. But not a voice in the selection of honorees and I made that clear. So it just became part of what I did.

Steve Cuden: Well, it certainly must have helped you that you were presenting them alongside some of the greatest artists of all time.

George Stevens: Exactly.

Steve Cuden: So what would you say when you were producing the Kennedy Center Honors, what were the biggest challenges? Was it getting the talent to come in? Was it setting the show up? What were the big, we’ve got this big challenge we’re going to go through every year. What was that?

George Stevens: After the first year, Nick Vanoff was my wonderful colleague and collaborator. We were starting from scratch, but we had this one key idea that we would show these biographical films. They were five minutes long. It started with Arthur Rubenstein leaving Austria, or Marian Anderson, the great first African American opera singer. They were in the first year and we made this five-minute documentary that was so moving, and with Marian Anderson being sent away from Constitution Hall because she was Black. And Eleanor Roosevelt invited her to sing at the Lincoln Memorial and to see her singing before 50,000 people, My Country, ‘Tis of Thee. That film ends. We didn’t show them on Little Screens. It was like a great radio city music hall. Huge screen. The lights came on and the audience as one stood and turned to applaud to the box. Those biographical films became the secret because people came in and they might have known who Fred Astaire was, but they didn’t know who George Balanchine was. So these films were the secret and we just put it together. But after that first year, which was so successful, the biggest challenge was, we’ve got to do it again next year. The expectations were so high. The little story I told about my father, keep working and working and working. Don’t give up. Keep looking for another idea and make it as good as it can be. We really succeeded at that over the years.

Steve Cuden: So you wrote for, what? 35 or 36 years you wrote shows?

George Stevens: 37 years.

Steve Cuden: 37 years. Did you start that process almost immediately after a show ended?

George Stevens: It was a year-round process. Start thinking about the honorees, who would it be next year, and who would it be the year after that and the year after that. Start to see where this journey was going to take us.

Steve Cuden: So that took up a lot of your life then for 37 years?

George Stevens: It did. I mean, I would do other things during the year, but every year I would do the Kennedy Center Honors.

Steve Cuden: Obviously you couldn’t start to write a script for the event until you knew who the event was featuring. Correct?

George Stevens: Exactly. Yeah.

Steve Cuden: How long would it take for you to set that up? Was it pretty easy to set up?

George Stevens: Finally, if we get the honorees selected in early August, and that was enough time because you didn’t want to select them in January, and something comes up to change their plans. So it worked well on that calendar.

Steve Cuden: So you also did all along the way, the AFI Life Achievement Award. Is there anyone along the way that you wished you could have gotten that you didn’t?

George Stevens: Perhaps my father.

Steve Cuden: Oh, that would’ve been a good one.

George Stevens: But he died too soon, and I did not want to in those early years. I once said he was, they nominated him at the selection committee meeting. I said, well, if you were to honor him, I’d have to leave as director. Somebody said, I call for the question.

Steve Cuden: So perseverance. You already alluded to perseverance as being part of a career. You talked in the book about your pursuit of Cary Grant for the AFI Life Achievement Award, and that he turned you down. That you wound up with John Ford as your first guest. So that’s the proof that you have to be persistent, I guess is the right word.

George Stevens: Yeah. Oh yeah. Absolutely.

Steve Cuden: It also took you, what, six years to get The Murder of Mary Phagan produced?

George Stevens: It did. We started, and then we submitted a script and they said, no, we want to make a movie about Yoko Ono anyway. Then finally they came back, and we did it, and it won the Emmy for NBC.

Steve Cuden: So you also write in the book. I’m quoting now. “Networks have layers of program executives in whom I have found two common qualities. They lack storytelling skills and are afraid of being fired.” I think those are absolute truths because I’ve had plenty of those experiences myself. How does one in the business break through those two issues, a lack of storytelling and ability and a fear for their job? How do you as an artist, break through that wall?

George Stevens: It’s you just use all your tricks. It’s different in any case. I love the fact of the story of the Brown versus Board of Education. Thurgood Marshall, a young Black lawyer, organizes a group of lawyers and decides to take the injustice of segregated schools, which were approved by the Supreme Court in 1905. He wants to have that repeal in the Supreme Court. It’s a great story, and it’s not the easiest story to go pitch to a network. That I did have a secret weapon. I thought I could get Sidney Poitier, who never did television to play Thurgood Marshall. But I was doing the Kennedy Center Honors, and I’d made some little forays to the networks, and the response was lukewarm.

General Motors loved the Kennedy Center Honors, and they had become complete sponsors with their Mark of Excellence program. I went to them and gave them the script I’d written for Separate But Equal. They said we will sponsor it entirely.

Steve Cuden: Nice.

George Stevens: Then it was just a question then of negotiating with which network was going to do it.

Steve Cuden: They of course, trusted you at that point. They knew who you were. You were a known entity. You had worked with them for a while, and so that greased the wheel a little bit, I assume.

George Stevens: It did. I wanted to direct this. I had not been directing since I was doing Peter Gunn and stuff like those 20 years earlier. So I knew the network would likely want somebody they were comfortable with because they could question whether I would be good at it. But then I knew if I got Sydney, Sidney trusted me. So when I said, I’m going to direct this, they realized that Sydney approved it and that made it. I directed it and did a job good enough to win them the Emmy for outstanding miniseries.

Steve Cuden: I can’t think of anybody who would open more doors than Sidney Poitier.

George Stevens: Oh God. He was such a wonderful figure.

Steve Cuden: So you’ve worked with lots of truly famous people. You’ve known personally, lots of truly famous people. What defines what great professional artists and politicians have that makes them special or unique? Have you ever given any thought to that?

George Stevens: I don’t think there’s a uniform quality. In the arts, I think there’s always this sort of to really get to the top you pursue your craft, you learn, you work, you get better, and you have to taste. You want to be involved in good things. That’s really the hallmark.

Steve Cuden: Well, I’ve asked you a pretty much impossible question to answer, and it’s a great response. It’s this infamous “It factor” that no one can put their finger on that makes a star a star. We don’t know what that is. It’s just something that we as humans recognize in this person that we’re watching on a screen. That they have something we want to watch more of. I don’t think you can sell it. I don’t think you can buy it. You can’t go to a store and become a star. It just is. So I think that that’s a very interesting thing about stars in general. Do you have any advice for selling shows to Hollywood for pitching, for taking your stories and making them palatable to those that need to buy?

George Stevens: Gosh, it’s always changing. Now so much of it is for streaming. You have to understand clearly what you want to do. I’m working on one now and it’s just to put yourself in the mind of the person you’re speaking to. It be a studio head or a sponsor or whatever, and try to engage them in this idea and make it compelling and be prepared to answer the questions of how you’re going to get it done. That I think Sidney Poitier wants to do it. Whatever your deck of cards you’re playing.

Steve Cuden: All right. So producing unquestionably and directing unquestionably comes with built-in pressures. What would you do when you felt pressure? How do you handle pressure?

George Stevens: I try to keep calm, believe in what you’re doing, and look for ways to diffuse the pressure. We’re talking about Sydney. I’m directing Separate But Equal, and I’ve explained that it was really them knowing that Sydney wanted me as the director. We were working along, and it’s all going very well. Sydney’s just done a couple of scenes and it had moved, and we were shooting in Charleston, South Carolina. We built the offices of the NAACP where the lawyer is. Sidney as Thurgood Marshall had been to South Carolina and gotten a group of people to say they would sign a petition, which would enable him to file a case in South Carolina. He comes up and he comes in late to the New York City offices, and he puts down his briefcase and he sees there’s a poker game going on among the lawyers, three or four of them. They’re having a drink late at night. He goes in and he sits in the poker game, and the scene is about he’s going to stop and tell them about this case in South Carolina, which is going to lead them to the Supreme Court. I had not seen the movies that Sidney did with Bill Cosby, which were a lot of comedy. I sort of knew Sidney from the Heat of the Night and the Defiant Ones. Sidney was kind of doing a little, and it didn’t feel right to me. So I kind of took a break and I took Sidney aside and said, let’s just have a little talk. We went into, and we ended up in a kind of room full of props, kind of a cluttered room. I said to Sidney that I don’t think we have quite the tone we need in this scene. Sidney just kind of face, and it gets too quiet. Well, maybe you will tell me just what you want. I said, well, here we go. This was nice while it lasted. I don’t know where it came from, but I looked at him and I said, Sidney, I think of Thurgood Marshall as a man with secrets.

Steve Cuden: What a great line.

George Stevens: He looked at me and he said, whenever that’s what you want, say that word. We never had another difficulty through the end of the picture.

Steve Cuden: That is what you call an easily directable actor.

George Stevens: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: I have been having the most fun conversation with George Stevens Jr. I’m just wondering, you’ve already told us all these amazing stories, but do you have any particular story in mind that’s either weird, quirky, offbeat, oddball, or just plain funny that you can share with us?

George Stevens: I wrote a play called Thurgood, which I wrote for Sidney Poitier, but Sidney who loved it and wanted to do it had just turned 75. He felt he really didn’t want to be on the stage alone for two hours or an hour and a half by himself. So that boulder was at the bottom of the hill. But then I found out James Earl Jones would be interested. So we did it in Westport, Connecticut and he was just wonderful. He just took this play, and it was so great, and we were doing it up there. We really thought it was going quite well. My friend John Guerra, the playwright. A great playwright. Six degrees of Separation. One of our best living playwrights. He came up and watched it. The next day we’re talking and he said, well, yeah, it’s really very good. He said, one thing you might think about. He says, Thurgood Marshall comes out and comes on that stage. I’m sitting there listening to this, and I’m saying, why is he telling me all this stuff? I said, what do you mean? He says, the audience, he says, you have 10 minutes. Moss Hart, the great director, had told John, you have 10 minutes and the audience better know what you’re doing with them by those 10 minutes, then they’ll stay with you the whole way. He said, people need to know why he is there and why he is doing this. So we made it that he was speaking. He’d gone back to his alma mater, Howard University School of Law. He comes out and he’s talking to the students at Howard University, and all of a sudden, everything he said had a reason. From then on, the play just flowed. But it’s how one piece of advice, you should keep your eyes and ears open because somebody well informed can give you advice that is invaluable. John Guerra did that for me on Thurgood.

Steve Cuden: Well, that is fantastic. I mean, because yeah, you needed that little… You were probably a little bit lost, and so he comes and sees something that you’re not seeing and bingo. There you go.

George Stevens: I am writing my first play. John’s written a lot of plays.

Steve Cuden: Yes, he has. He wrote House of the Blue Leaves, didn’t he?

George Stevens: He did.

Steve Cuden: He did. Yeah. So last question for you today, George. What’s the best piece of advice that you like to… I mean, we’ve already heard tons of advice from you, but what’s the best piece of advice that you like to give to those who are starting out in the business, or maybe they’re in a little bit and trying to get to that next level?

George Stevens: I tell them one, to believe in themselves. It is so hard. You’re going for auditions, you’re going for interviews, you’re trying to persuade people, and you’re going to work very hard. Keep working very hard but believe in yourself and keep knocking on doors. Keep trying. There may be a point where you finally say, this is not for me. But the chances are, if you’re working to be an actor, you’ll probably become an actor. That maybe you’ll become a production assistant, and then a producer. People get into this creative world, and they find out what they’re good at. So keep working and keep your eyes open.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s spectacular advice, and really, truthfully, what most people need to know, because it does take persistence and time and energy and all the rest of it. George Stevens, Jr. this has been so great to have you on StoryBeat Today.

George Stevens: I’ve got to ask you. Do you think people are now going to go read or listen to the audio version of My Place in the Sun?

Steve Cuden: I was just about to say they should go out and either read or listen to the audio version of My Place in the Sun. Because if you want to know about how Hollywood worked from the very beginning, because you cover a lot of that, and if you want to know how politics in Washington works, and if you want to know how TV production works, this is a book for you. It’s extremely well written and so much entertainment in one nice chunk of storytelling from your whole life story and your family’s life story. I enjoyed it thoroughly. I really did. George Stevens Jr. this has just been a fantastic hour on StoryBeat, and I can’t thank you enough for joining me on the show today.

George Stevens: I had a great time with you, Steve. Thanks so much.

Steve Cuden: So we’ve come to the end of today’s StoryBeat. If you like this episode, won’t you please take a moment to give us a comment, rating, or review on whatever app or platform you are listening to. Your support helps us bring more great StoryBeat episodes to you. StoryBeat is available on all major podcast apps and platforms, including Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, iHeartRadio, Stitcher, Tune In, and many others. Until next time, I’m Steve Cuden. May all your stories be unforgettable.

0 Comments