Entering the world of professional entertainment at the age of five, Bill has worked on over 400 television shows and is best known by fans around the world for the creation of many memorable roles, including: the iconic heroic boy astronaut, Will Robinson, on the long-running classic TV series Lost in Space; Anthony Fremont from The Twilight Zone; and Lennier from the popular science fiction series Babylon 5, in which he co-starred for five years.

As a prolific songwriter and recording artist, Bill has produced numerous solo CDs, as well as being half of the infamous novelty rock recording and short filmmaking duo, Barnes and Barnes, best known for the classic demented song and film Fish Heads. He’s also worked with the pop group America off and on for over 30 years, composing, producing, and performing with the band.

Bill has also served as a consulting producer on the long-running hit TV series Ancient Aliens.

He’s written scores of comic books and television shows. And he’s collaborated with his Lost in Space co-star, Angela Cartwright, on three books. Bill’s autobiography, Danger Will Robinson: The Full Mumy, was recently published by Next Chapter Entertainment. It’s filled with fantastic stories and photos from Bill’s remarkable career in show business.

WEBSITES:

BILL MUMY BOOKS AND MUSIC:

IF YOU LIKE THIS EPISODE, YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY:

- Michael Wolff, Jazz Pianist-Composer-Bandleader-Episode #225

- Candi Milo, Voiceover Actress-Author-Episode #219

- Apollo Dukakis, Actor-Director-Episode #213

- Robert Miller, Singer-Songwriter-Musician-Episode #189

- Cary Elwes, Legendary Actor and Best Selling Author-Episode #187

- Adam Hawley, Jazz Guitarist-Producer-Episode #185

- Peter Jurasik, Actor-Hill Street Blues-Babylon 5-Episode #183

- John Davidson, Singer-Actor-Host Extraordinaire-Episode #164

- Troy Evans, Actor-Episode #150

- Kathleen Chalfant, Actress-Episode #148

- Bryan Cranston, Legendary Actor-Producer-Writer-Director-Episode #132

- Fred Rubin, Television Writer-Producer-Episode #130

- Marley Sims, Actress-Screenwriter-Episode #129

- Tamara Tunie, Actress-Director-Producer-Episode #68

- Kelly Ward, Actor-Writer-Director-Choreographer-Episode #66

- Austin Pendleton, Legendary Actor-Director-Episode #41

- Phil Proctor-Encore-Episodes #33 and #34

Steve Cuden: On today’s StoryBeat…

Bill Mumy: I was standing behind the camera for her closeup, and I was goofing around. Please remember, I was six. I was goofing around. I was kind of making faces at her to be fun. Again, the mighty Cloris Leachman very calmly took me aside, and told me, whether you are on camera or off camera, you always have to do your best. You always have to help the other actor by being as good as you can. You can’t goof around because the camera doesn’t see you. Another very big lesson learned at the age of six from the mighty Cloris Leachman.

Narrator: This is StoryBeat with Steve Cuden, a podcast for the creative mind. StoryBeat explores how masters of creativity develop and produce brilliant works that people everywhere love and admire. So join us as we discover how talented creators find success in the worlds of imagination and entertainment. Here now is your host, Steve Cuden.

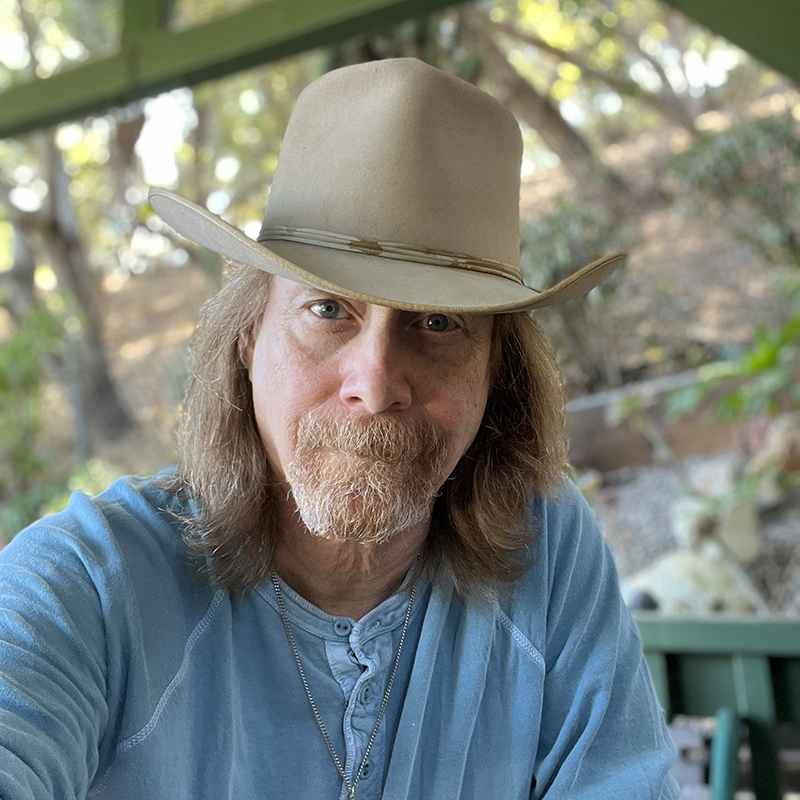

Steve Cuden: Thanks for joining us on StoryBeat. We’re coming to you from the Steel City, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Well, you’re likely to already be a fan of my guest today, Bill Mumy. You know him as an actor, songwriter, recording artist, producer, voiceover artist, musician, photographer, and writer. Entering the world of professional entertainment at the age of five, Bill has worked on over 400 television shows and is best known by fans around the world for the creation of many memorable roles, including the iconic heroic boy astronaut Will Robinson on the long running classic TV series Lost in Space, Anthony Fremont from The Twilight Zone, and Lennier from the popular science fiction series Babylon Five in which he co-starred for five years.

As a prolific songwriter and recording artist. Bill has produced numerous solo CDs, as well as being half of the infamous novelty rock recording and short filmmaking duo, Barnes and Barnes, best known for the classic demented song and film, Fish Heads. He’s also worked with the Pop Group America off and on for over 30 years, composing, producing, and performing with the band. Bill has also served as a consulting producer on the long running hit TV series, Ancient Aliens. He’s written scores of comic books and television shows, and he’s collaborated with his Lost in Space costar, Angela Cartwright on three books. Bill’s autobiography, Danger Will Robinson: The Full Mumy was recently published by Next Chapter Entertainment.

I’ve read Danger Will Robinson and can tell you it’s filled with fantastic stories and photos from Bill’s remarkable career in show business. I highly recommend it to you. So for all those reasons and many more, I am deeply honored and truly thrilled to welcome someone I’ve been watching and admiring my whole life, the extraordinarily multi-talented Bill Mumy to StoryBeat today. Bill, thanks so much for joining me.

Bill Mumy: Wow, well, it’s my pleasure. I’m quite impressed hearing all that. You make it sound better.

Steve Cuden: I think you live up to your reputation quite well. So you are the first person I’ve been privileged to interview in over 230 guests I’ve had that started in the business as young as you did. Clearly you had to have been a natural actor. You didn’t spend years and years in training prior to starting in the business. Did you know at that time that you were actually pretty good at it, or were you just a kid having fun back then?

Bill Mumy: Well, I was kind of a slacker. I didn’t get started really till I was five.

Steve Cuden: What took you so long?

Bill Mumy: I knew that was what I wanted to do from the age of four when I had broken my leg and I spent about 10 to 12 weeks in a cast. I couldn’t go run around with my pals on our idyllic 1950s cul-de-sac in West Los Angeles. So I just stayed home and watched the Mickey Mouse Club and Zorro and George Reeves the Superman. Something about those two Cape Adventurers along with some other stuff, Spin and Marty the Lone Ranger, I really wanted to get inside the television, and I bugged my family. You can’t escape your destiny and it worked out. In terms of me recognizing that I chose wisely for myself or that I was good at it, I’d have to say that probably after a year or a year and a half, I did realize that. Because I booked the vast majority of auditions that I would go on.

I would go into that room, and I would read the scenes. I didn’t read them because I didn’t even read. I was six or something. I would perform the scenes and then I would book those gigs. So, at the beginning I don’t think I understood that I was booking them because I was good. I just was happy to do it and I enjoyed it. But after probably about a year of prolifically working, I did start to understand that I was pretty good at that. I knew how to do it.

Steve Cuden: It was your decision to start acting? Obviously, your parents said yes. It wasn’t their idea. Correct?

Bill Mumy: A hundred percent my idea. I was an only child. My parents had me late in life. My dad was 50, my mom was 41 when I was born. Maybe my dad was 49. We lived in West LA. My mother had worked at 20th Century Fox Studios as a writer’s secretary for 11 years before she married my dad. Her father, Harry Gould, had been a very successful agent in Hollywood. But he mostly represented writers and directors. But he did represent Boris Karloff, and he got him the audition, as you know, for Frankenstein and negotiated those deals for him. My grandfather Harry had passed away before I was born. But my point here is my family and my father, at that point in our life in the mid-1950s, my father was a wealthy man.

So his response to my mother was, well, if he really wants to do it and you want to go with him and check it out, go ahead. I did really want to do it. So my mother booked me on a regional show that civilian children were working in called a Romper Room, which was basically just a preschool on television, and they were regionally shot all over the country. So I went to do Romper Room, and her reasoning for that, which I think was wise, was to see how I would react on a set under lights with camera. Would I take directions or would I be… I did and I stayed on Romper Room for a couple of weeks as opposed to, I think, most people signed up for a week and I stayed longer.

Anyway, it was a hundred percent of my energy that led to that. My parents weren’t intimidated by television or the show business. It wasn’t something that had some phony allure to them. They understood it, especially my mom. It worked out okay.

Steve Cuden: I assume it was a little bit of a gentler time than it is today in the business. Not quite so hurly-burly. But still, it was the business.

Bill Mumy: Yeah. I mean, there’s a big difference, and I’m sure we’ll get into this in more detail. But of course, there’s a big difference between play and acting or art and show business. They’re completely separate categories in a way although they all merged together at certain times, especially if you’re a little kid. There’re rules in place, and those rules were in place by the time I was old enough to start working professionally. There are child labor laws and there are Jackie Coogan Laws where a certain percentage of a minor’s income is placed in a trust for them so that when they come of age, they won’t have nothing. Now, my parents invested all of my money earned as a child actor quite well and didn’t need it for their own wellbeing. I do know lots of ex-child actors whose parents relied on a lot of their income. When they came of age there was very little for them.

Steve Cuden: Nothing left.

Bill Mumy: Well, there’s something, believe me. I mean, the Jackie Coogan rule. I don’t remember what it is. It’s not a lot, but I think it’s 20% or something. Don’t quote me on the percentage. But the parents could take the majority of their child’s money if they needed to or wanted to. That was never the case with me. Although I do know a lot of people that that was the case with, and I can certainly understand how that can lead to a lot of frustration and unhappiness. But that was not the case with Billy Mumy.

Steve Cuden: Did you receive any kind of formal training, or did you just learn by doing it? You were just good at it?

Bill Mumy: Yeah, I was just good at it. Eventually, a few years into it, I can’t pinpoint exactly when, there was a lady named Lois Auer, A-U-E-R, and she lived up on Mulholland Drive here in LA. I used to go to Lois on a Sunday morning at 10 and spend one hour with her memorizing the next script for four years of Lost in Space or whatever. I would go, my dad would drive me to Lois. He’d sit outside or he’d run an errand. Lois and I would go over the script, and I would have the script memorized completely in an hour. I was very, very, very good at that and I’m still. I mean, I’m not working right now on camera much, but I’m still very capable of, I guess you would call it an auditory memory skill. If I say something out loud, I will be able to maintain that. When I was a little kid, I was really, really, really good at that because I would learn everyone’s lines.

Steve Cuden: That was certainly your revealing. That’s part of your secret because that’s a gift. Not everybody has that, and that certainly had to have helped you walk onto a stage and be in it because you had all the lines.

Bill Mumy: I mean, it definitely did. I mean, everybody has their gift, whether you can throw a fastball if you’re in little league, or whether you can paint a really good-looking horse if you’re five years old. I mean, everyone has their gifts, and I think that my gifts were properly explored and exploited as a child happily. They were happily done. I remember very clearly when I was six, and the first starring episode that I did on television was an episode of the Loretta Young Show. It was the first time I worked with a great Cloris Leachman and Cloris played my mom four times eventually. Any actor who worked with Cloris would tell you she bumped your game up considerably and she really brought you to get the best you could bring. She made you rise to your highest level. On that first show I was working with her, and as we were rehearsing master shots and things, she would go up on her lines and I would tell her what they were because I had memorized them. I did that more than a couple times. Then Cloris explained to me that she had a process and she appreciated me knowing her lines, but she wanted to find them by herself. So that was a very early learning thing for me. I very, very, very rarely ever told anyone else who was searching for their lines, what their lines were to be.

Steve Cuden: Even though you knew them.

Bill Mumy: Even though I knew them. Cloris also taught me on that Loretta Young Show, which was called My Own Master, we had done a heavy scene where I had to cry or she had to cry, and it was a big, heavy, dramatic scene. Then we were getting into coverage, and I was standing behind the camera for her closeup, and I was goofing around. Please remember, I was six. I was goofing around. I was kind of making faces at her to be fun. Again, the mighty Cloris Leachman very calmly took me aside and told me, whether you are on camera or off camera, you always have to do your best. You always have to help the other actor by being as good as you can. You can’t goof around because the camera doesn’t see you. Another very big lesson learned at the age of six from the mighty Cloris Leachman that I never, ever goofed-off off camera again after that.

Steve Cuden: You were immersed early on in professionalism, and it wasn’t through a class, it was through the real world. That’s a huge difference, I think. Many people don’t get that kind of training until much later in life.

Bill Mumy: Well, many people don’t get the opportunity to work with countless iconic actors and directors and producers like I did, which was a really a great thing if you do look back at the eclectic diverseness of my early catalog, because a lot of child actors, this is great. It’s good for them, whatever. But a lot of child actors end up on a television show that runs for maybe seven years or something. They play the same character and it kind of becomes easy. Whereas what I feel was a great blessing for me was from the age of five to the age of 10 and a half, which is more than half my life, and a lot of work in that period.

I would go from a drama to a sitcom, to a western, to a doctor show, to a lawyer show, to a feature film, to a Disney movie. I mean, I was constantly exploring various different characters from the sick kid to the smart ass, to the mutant, to the cowboy. I mean, all that stuff. So the ability to have that versatility and to work with so many people as opposed to… Again, this is not saying anything negative about the opportunity to say, work with Donna Reed for seven years or something like that. But I really got to work with a variety of incredible, talented, iconic people. I think that you can’t help but absorb and learn from that, even if you aren’t consciously trying to.

Steve Cuden: You write in your book that you are a restless man and that you need to be creative all the time. Was that so when you were a kid as well? Were you very imaginative as a child?

Bill Mumy: Yes. I was totally so. I’ll give you an example. Let’s just jump into the Lost In Space years for a minute, because I was there from the edge of 10 to 14. Needless to say, the character of Will Robinson, along with Dr. Smith and the Robot eventually pretty much carried the show. I worked extensively in that, and I loved every second of it. Will Robinson was exactly what I wanted to be. Zoro, he was Superman. He was a superhero. I loved that. I would have quite a lot of scenes in every episode. I had to go to school three hours a day and do reasonably well. I had to go to lunch. But even still, with all of that going on, I still managed to write and draw comic books almost every week about the Lost in Space cast.

Steve Cuden: Wow. Really?

Bill Mumy: Yeah. Guy Williams and June Lockhart, they were the comb and caramaya. Mark Goddard and myself were Captain Panther and Fox. All I’m saying is in terms of always being restless and always having that creative need to combust with something has been with me forever. I brought my guitar with me to the sets always. I started playing at 10, but the reason Will Robinson ended up playing on five or six episodes of Lost In Space was because Irwin Allen saw if he’s not here, he is playing his guitar over there. So yes.

Steve Cuden: Were you writing songs at that age too, or did that come later?

Bill Mumy: I started writing songs at 11.

Steve Cuden: At 11.

Bill Mumy: Yeah, my first two songs at 11. I used to go out for a promotional personal appearance. During hiatuses and stuff I’d go to county fairs and things, or radio shows and all over the country. I’d bring my guitar and be this little troubadour and I would play songs of the day and a couple that I had written. I remember co-hosting a talk show. It was a network show called The Woody Woodbury Show, and I co-hosted that for a week. Michael Melvoin was the musical director, and I played songs that I wrote.

Steve Cuden: At what age? You were 11?

Bill Mumy: Yeah, I might have been. The first two songs I wrote, I was 11. I Hear the Train, it’s not embarrassing. It’s not bad. The first one I wrote was called Traveling Bill. That one will stay in a locked file. It was me trying to be the Kingston Trio.

Steve Cuden: Many people who are creative, many that I know and many I’ve read about, will claim that the work comes through them. That they’re not actually creating. That the work is coming through them from somewhere, whether they call it God or the universe or energy, or whatever they want to call it. Do you feel the same way about your creativity, or do you feel like you are the instigator of the creativity?

Bill Mumy: There’re different categories of that. As a songwriter, there’s nothing that I respect and appreciate more than the muse jumping into me. Without even consciously turning on a radio, you get this signal. It comes to you. I learned, oh my gosh, at least 30 some years ago. I don’t care if I’m at a dinner party. I don’t care if I’m at a Lakers basketball. If I start to get this idea, then I’m going to listen to it, respect it, and see how far I can take that.

Steve Cuden: If you’re at a party or at the Lakers game, do you carry something with you to write it down? Or what do you do?

Bill Mumy: In the past, there were actually times when I would drive to a guitar store if I wasn’t near my house. I would go off into a corner of a store, pick up a guitar, and I’d go off into a corner of the store and find out exactly what that melody was or that progression was, or flesh out a few lyrics. Nowadays I have an iPhone, like most, or whatever you call it. A smartphone. So if I do get an inspiration, I can just talk into it, and it stays there. But I’ve learned never, ever to ask the muse to be put on pause. I don’t ask it to come back tomorrow or at a better time. If I’m getting something inspiring, then I will see it through to the best of my ability. But on the other hand, after so many decades in the entertainment business or art business, whatever you want to call it, I’m a craftsman too.

If somebody asks me to write a theme song or let’s just say America was going to make a record and Doey has a few half-finished ideas. I will sit down and we can do that. I can be a craftsman and get that done. As an actor, the vast majority of my work as an actor, I didn’t write. So that to me is very different than receiving an inspiration. Here it is on the paper, and I’ve always done two things. One is I would learn it, memorize it, and I would create a character that was reasonably true to my own inner self, but always believing in the framework that I was placed in. Whether that was a hundred years ago or a hundred years in the future.

Whether I was adventurous or whether I was meek. I could put myself into those scripts and I would do it. Then the second thing that I would do is I learned very early on to listen to what a director wanted. So if a director wanted somebody to be quieter or zippier, just directed me.

Steve Cuden: You learned early on to be malleable in receiving that direction.

Bill Mumy: Yes. But as a child actor, I rarely was off the mark in terms of what they wanted. I would’ve gone in and auditioned, and they would’ve said, great. Can we book Billy? There wasn’t a lot of, okay, I’ve booked this gig and my interpretation of what you want me to do is very different from yours. I mean, there were always some tweaks here and there, but generally I was pretty close to what they wanted.

Steve Cuden: Clearly, you worked so much that that’s evident. You weren’t going in and they were struggling with you. You were just coming in and doing it, and that’s why you were who you were back then, where you were constantly being booked. So you are mainly known, I think, for working in dramas. But a lot of the dramas you’ve been in have a light edge to them, and you’ve also worked in a bunch of comedies as well. Do you have a particular preference for one or the other?

Bill Mumy: No, I don’t. My preference was always kind of to be in a comic book vibe. I mean, as an adult, I remember doing a few things I’d never done before. I called the producers at Warner Brothers on the original Flash Television show. I didn’t know them, but Mark Hamill is a good friend of mine. Mark had done a couple episodes, and David Cassidy was a friend of mine, and he had done an episode I was like, I’m watching The Flash and I want to be on the Flash. I called the producers not through an agent, I just called them on the phone. It was interesting because it’s not my nature to do that, but sometimes you really do have to take your shot. I remember sitting there and calling. Hi, it’s Bill Mumy for Danny Bilson and Paul De Mayo. Who? It’s Bill Mumy. What is this regarding? The Flash. Hold, please. I could easily have been blown off. I mean, right?

Steve Cuden: Sure.

Bill Mumy: But as it turned out, they took my call and I went and then did a nice guest shot on the Flash, which made me very happy.

Steve Cuden: In terms, they knew who you were of course.

Bill Mumy: Yeah, they did, of course. But it still was a bold thing, in my opinion for me to do. It wasn’t something or isn’t something that I have done much since.

Steve Cuden: Most people would not get to them at that point if they didn’t know who you were in some way, whether you were referred in or so. If I called them on the phone, they wouldn’t have answered my call, but they would answer somebody like you because they knew who you were. So that was helpful. But like you say, they could have easily blown you off too.

Bill Mumy: Yeah, I think. Of course, that’s true. I think in terms of your theme, so to speak. I was basically saying sometimes you have to be pushy if you’re trying to get into show business. If you can say, hey, call somebody and say, hey, I know this guy who you work with, and he said I’d be good for this. There’re so many different levels of achieving, and now there’s so many more shows than there ever were. When I was working prolifically in the old days, so to speak, there were only three networks. There were no cable shows, there was no streaming, there was no internet, there was no YouTube. I mean, none of this. It was just CBS, NBC, and ABC.

Steve Cuden: People couldn’t take their home video camera and go out and make a movie. You had to go and get a big expensive set worth of cameras and lights and everything else. Not anymore. So there’s a lot more opportunity.

Bill Mumy: Exactly. There’s no comparison in terms of the opportunities to create decent work now at almost no budget whatsoever. When I first started going into the recording studios, my band was in record plant a lot, and it was $300. Not that I was paying for it, but it was $300 an hour, and you had all of this big 24 track, two-inch tape and all that stuff. Now you can almost meet that quality on an iPhone.

Steve Cuden: For sure. It’s crazy.

Bill Mumy: I mean, almost.

Steve Cuden: So, I want to talk for a moment about acting specifics. Your process as an actor. When you get a script, you book a gig, you’ve gotten a script, where do you start? Aside from reading the script, which is the obvious, but where do you begin to develop a character? How do you go about it? What’s your process?

Bill Mumy: Well, I’ll read it out loud by myself several times and find an Iambic pentameter that I think fits the dialogue. I’ll look for a rhythm to the way a certain character might speak. I might emulate someone I know personally. I might emulate someone I don’t know, but that I know their tonality. Then generally, my wife, Eileen, we’ve been together 40 years, so that covers some time. She’ll work with me. She’ll cue me. She’ll sit and cue me, and she’ll give me feedback. By the time I go to work, whether it’s an eight-day drama or whatever, but by the time I go to work, I will feel very prepared. I won’t go to work not knowing my lines. So I’m always pretty confident in the fact that I won’t get there and blow it. We’ll put it that way.

Steve Cuden: Has that process become easier for you over the years?

Bill Mumy: I don’t seek out on-camera work much. I did five years on Babylon Five with this alien makeup on and stuff. By the way, the character of Lennier that I played in Babylon Five was based on a cross between a friend of mine, and I hate to say this, but it’s true, tonally. The voice was based on David Carradine in Kung Fu, a little bit.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

Bill Mumy: But you can hear it in there if you listen to it. With that in mind, you’ll go, oh, yeah, I can hear that. So I did base that Lennier totally on David Carradine and a guy you wouldn’t know. I don’t know if I find it easier or anything like that. Acting is not something I do at home. Acting for me after the age of 17-ish is a gig. It’s a job. I like it. It’s much better than being in Afghanistan. It’s a gig. So I don’t sit around my house, although I write characters and television and comic books and things. But I don’t really consciously sit around and act. Whereas making music is something I will do because I’m compelled to do it. I will doodle. I will paint a little bit. I will write stories.

Those things I do, because I hate that word, but it’s true. I’m compelled to do it. Acting-wise it’s something that comes along. In the last decade or so I’ve chosen really not to throw my hat in the ring largely because—I don’t mean to say it self-servingly, but of course everything we do is self-serving. Our union, the Screen Actors Guild has really been whittled down incredibly from what it used to be. People can work as a professional actor now for a whole lot less money than I was working for 50 years ago. So that rubs me wrong.

Steve Cuden: It’s crazy, isn’t it?

Bill Mumy: Well, it’s disappointing. There were always certain things that were, I felt, forever in place. If you go to location, they fly you first class. Well, they don’t do that anymore. If you go to a location, they pick you up, they take you there and they bring you and they give you per diem. They don’t do that anymore. It’s all a very different schmooze in terms of something that I dealt with as a child was the lack of continued residuals. There’s no point in me whining about it. It’s just the work you did prior to 1974 or 75, they don’t pay you residuals for that work. Well, there’s a whole lot of building booming work.

Steve Cuden: A whole lot.

Bill Mumy: I mean, if I got paid when Lost in Space was running now, or Twilight Zones were running now, or Bewitched or Monsters, or I Dream a Genie or any of those. I mean, I don’t want to sit here and name all those shows. But I mean, if I got a pizza for every time one of those shows was running, I’d have a lot of pizza. So when I see the reality of a working actor now being paid so little and treated so less than well as we all used to be treated and I see so many hungry guys who would cut off a toe to go do four lines on a Law and Order. Let them have it. Do you know what I mean? Let them get it. I don’t care. I don’t really want to do that.

Steve Cuden: Your focus has become on music. It’s mostly music and art and other things that are still creative, but not necessarily in the acting business so much.

Bill Mumy: I would love to be working on a good project as in a film or television if I felt the package was right. Otherwise I’m fine. I mean, I’m 68 years old. I started working at five. I don’t need the money, but I don’t like the idea of working without receiving it. I’d like to do it, but only if it’s something good. Do you know what I mean?

Steve Cuden: You wrote in the book, and you put it in several places, how much money you got paid for certain shows.

Bill Mumy: I’ll say this about the process of writing the book. I am very actually Covid cautious. I see my family. I see my son and my daughter and my grandchildren. Other than that, I don’t go out or go into places very much. So during the last two years and nine months, I’ve been incredibly prolific and productive from my house. I mean, I’ve made a lot of records. I’m working on a musical play with Paul Gordon, a Tony nominated talented guy who I used to be in a band with. I’ve painted a lot. I’ve managed to get another three seasons in consulting producing on Ancient Aliens. We just got picked up for a new season. I’ve got notes here to give when you and I are wrapped up on six acts of the upcoming episode. I haven’t been interested in kind of going to a soundstage and sitting in a honey wagon to hit my mark and be the villain of the week for a couple of days.

Steve Cuden: Because of technology, you can do it from your home. You don’t have to travel.

Bill Mumy: Exactly. I haven’t been on a plane in almost three years.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

Bill Mumy: I know a lot of people, and I say this, a lot of impressive people, Beach Boys, Ringo Star, the Band of America, that level of people that are friends of mine, and they’re out on the road again, thinking that that was safe to do. Boy, it hasn’t been. Tours get canceled midway through. You’re stranded in a hotel somewhere for two weeks or a week or whatever with a fever, wondering, how the heck did that happen to me? I can’t tell you the amount of airplane airport nightmare stories I’ve heard in the last couple of years from just the way people are acting and treated it on planes and stuff. I like to perform and every week I play live on my social media. I try to entertain people. But no, I’m not looking to rush out there and get on a bus.

Steve Cuden: What I’d love to chat about, because you’re triggering this thought about how do you deal with challenges in the entertainment industry. You write in the book about the physical challenges you went through on Babylon Five with the makeup, and you’ve had other challenges. You write in the book about the physical challenges of working on Papillon and so on. How do you look at challenges? Is it something that you must work your way through? Do you have a technique or a thought as to how you work your way through those challenges? In the case of Covid, you’ve overcome them by working at home, but you can’t do that for virtually everything always. So do you have a thought about how you overcome difficulties in production or out of production?

Bill Mumy: Well, out of production, it comes down to what something has a value to you. If you really want to do something. If you really want to be a part of a certain project or do something, then you’ll just put up with those challenges in order to make that happen. But there’s also a level of—

Steve Cuden: It’s that simple? Just putting up with it? There’s nothing beyond that then.

Bill Mumy: Yes.

Steve Cuden: Just putting up with it.

Bill Mumy: Yes. There’s also that personal level of what we call our comfort zone. So how wide are you or anybody that we’re talking about. How wide are you willing to stretch your comfort zone? A lot of that depends on multiple factors. It depends on income or finances or security or reasons why, happiness. All these different things. I’m very happy in my comfort zone. So it takes quite a lot to get me out of it.

Steve Cuden: You and me both. I work at home. I’ve worked at home most of my life. Some of it out of the home. But I understand what you’re talking about. I’m good at being alone at home, working on writing another project. So I understand what you’re talking about. Not everybody can handle that, by the way. I have friends of mine, I bet you do too, who can’t stand being with themselves for long periods of time. They have to get out of the house. They have to go be with other people.

Bill Mumy: I definitely have very close friends that are like that. I consider myself to be restless, but not in a traveling description of that.

Steve Cuden: In a creative way. You’re restless creatively.

Bill Mumy: Yeah. I have friends that have been on the road for over 40 years. When they’re not on the road, for instance, when the first year of Covid restrictions hit us and everything was locked down. I have some good friends who are going nuts. It’s like their marriages were like, wait a minute, you’re here all the time. Wait, what is this? I thought you were going to be on the road for seven months. I have to look at you every day.

Steve Cuden: Have you been able to do any voice acting from home?

Bill Mumy: A little bit. I did a science fiction pilot. I did a couple of narration things. A little bit. It’s funny because it’s like waves at the ocean. They come in sets. My ability to read copy is not diminished from what it was 20 years ago or 15 years ago. But 20 years ago, or 15 years ago, I was working almost every day. It was great. Which was another reason why after Babylon Five, I wasn’t actively hungrily pursuing on camera work. I was saying, farmers get you back where you belong. For a heck of a lot of money, I was narrating e biographies. I narrated 53 of those. Wow. I was doing Bud Ice commercials and Ford commercials. It was just what a nice, easy appendage and arena of show business voiceover work is.

Steve Cuden: You don’t have to put all that makeup on.

Bill Mumy: You don’t have to put any makeup on. It’s great. I’m just being honest here. Like I say, it comes in waves. There is a period where, man, I was a hot voiceover guy. Right now I’m a cold voiceover guy.

Steve Cuden: That’s okay.

Bill Mumy: But I’m still here ready to speak. I’ll probably read the book as an audio book sometime next year.

Steve Cuden: Probably. Oh, you should. I’m not blowing smoke. You’re a really good writer. I assume you wrote it yourself.

Bill Mumy: No help. All me.

Steve Cuden: You are a really good writer. I’ve been writing my whole life. It’s very compelling to read. It’s fun to read. It’s easy to read. All those things are signs of a very good writer. So I truly recommend the book to anybody that’s interested in Hollywood, how the business works, crazy stories, because you definitely tell a few crazy stories in there. But it’s difficult when you say you’re a writer, if you don’t know how. You know how to write, which is a good thing.

Bill Mumy: Well, thank you very much. I wrote a lot of Marvel comic books in the eighties and early nineties and some DC comics, and other publishers. When you’re writing for big companies like that, you have editors, and those editors teach you what they need to teach you.

Steve Cuden: Of course.

Bill Mumy: I had co-created a a television series in the late nineties called Space Cases for Nickelodeon that was running around the whole planet for a while. Two seasons. And again, that’s where you learned. I learned that you have to accept stupid network notes. You have to. No, I’m so serious about this. This is really, in terms of giving advice to people. If you are going to enter show business, and if writing is a part of your thing, you have to accept that people are going to try to dumb your stuff down. They’re also going to just kind of justify their own paychecks by saying, yes, in Act Three, you have this as a blue room. I think it would be much better if it was an orange room. You just go, yeah. Great idea. That’s great. That’s a great note. Thank you.

Steve Cuden: That’s your technique for taking notes. That was a question I have on my list of questions for you is how do you deal with notes, which is a really good thing to cover. You just indicated. Am I right to assume that you just take the note, accept it, tell them that it’s fine, and then go off and either ignore it or address it in some way? Yes?

Bill Mumy: Yes. I think the best way to do it is to make them think that you agree with their note and change your work as little as possible to appease the powers that be and still be true to your project. Or not really lose something that you know shouldn’t be lost. But if you have to lose something that you don’t want to lose, you’ve got to get to a place where you can just lose it. You have to just say to yourself, there’s art and I can stay home, and I can write poetry, or I can write short stories, or I can do what I want knowing then I can put them up on the internet or whatever. Or I could get a job working for a network or a studio or a production company. If they’re going to want to say, change this, change that. You just got to do it.

You have to do it. Another thing, which is true, sometimes notes are good. Sometimes someone gives you good notes and you go, oh, okay. Alright. I can do that. That’s cool. Yeah. I see that point. It’s an interesting change. Let’s do that. The other thing that I recently was reminded of is you don’t lose an early draft of anything. It’s still there.

Steve Cuden: That’s right.

Bill Mumy: So it’s like, there’s no reason to not take a note and say, okay, let’s see where it goes. Let’s try this. Because your thing that they’re giving you notes on is still there for you. You can go back and say, this was better. Maybe they’ll say, you’re right, but we wanted to try it the other way. As the late great Rick Rosas the bass player, said to me a great line that I love to remind people of. It’s, you can’t erase it if you don’t record it.

Steve Cuden: Oh, yes. That’s absolutely true. I’m so glad you’re saying that about notes. Because I’ve taught my students for a long time, no matter how horrible the notes are, and they can be pretty horrible and stupid sometimes, take the notes, just say, thank you very much. Because occasionally that horrible note will actually trigger another thought that improves things that had nothing to do with the note. But the note itself triggers another thought. I assume you’ve had that happen.

Bill Mumy: I have had that happen and I’ve also had the most insane notes that you had to swallow. You just swallow them. When we were doing Space Cases, they’re out in space, and there was a scene where one of our characters had to go out to repair the ship and do a space walk. So the network said, well, why are they in this suit? We can’t really see them. Peter David, my writing partner, and I were like, because you have to wear a suit when you are outside in the vacuum of space. They were like, well, it’s a television show. Can’t we just send him out? No, you can’t. Well, we would prefer that he doesn’t wear the suit. It was one of those things where you just went, holy moly. Okey-Dokey.

Steve Cuden: All right. So let’s turn our attention to songwriting, which I know is a love of yours. When you get an idea for a song, is it usually lyrics first? Is it usually music first, or is it just come in all different directions?

Bill Mumy: Well, I get it both ways, but I get lyrical, rhythmic thing most of the time. I’m a multi-instrumentalist, and I find if I’m sitting in a piano, it’s more likely that I’ll get an instrumental melodic progression going without a lyric. But I usually won’t pick up a guitar and just start finding that if I don’t have a story or the beginning of a story, or some rhythm of a handful of more than a handful. You know a verse and a chorus or something. More often than not, I will get some lyrical lines in my head. Then I will usually actually physically write them down with a pen. If it’s three in the morning, I’ll speak them into my cell phone or the smartphone. But I do get them both ways.

Steve Cuden: Are they typically a hook? Are those things usually hooks or are they just something within a song?

Bill Mumy: No, they’re usually the beginnings of a song. They’re usually a verse. A lot of times I will get that rhythm to those lines of a verse, and I’ll write maybe four verses. Then finding the hook is the hard part. Because you’re on a groove with this verse thing, and it’s got a rhythm, and you know it. The B rhymes with D. It’s got this thing. You know it’s not done yet. So then you have to either wait for that hook to kind of jump into you, or you have to craft it and find the hook. Obviously, it’s best when the whole thing just combusts out of you in 20 minutes, which also happens quite a bit. Those are the best ones, or in my opinion, I end up feeling like those are the best ones. When you get a whole song in literally a half hour, and maybe you’ll spend another day or half a day fine tuning it. But basically, you’re gifted a song. That’s the best.

Steve Cuden: That’s a pretty typical routine for you to go through something like that. I mean, it’s not an intentional routine, but that’s typically the way that it unfolds for you. Where it’s either very quick or you have to spend a little more time on it. But I’m getting a picture here that you don’t dwell on songs for long periods of time like a painter might take a year to paint a painting.

Bill Mumy: No, I don’t. But on the other hand, I will find myself returning to an unfinished thing. Sometimes it’s 15 years old, really and something fresh in it that I didn’t recognize at the time and finishing it or using a piece of it as a bridge. Sometimes songs or parts of songs can be modular and find themselves new homes.

Steve Cuden: Do you produce songs?

Bill Mumy: Yeah. I have a nice studio in my house, and I play everything. I mean, it’s not that I want to.

Steve Cuden: Do you play drums and piano? What do you play? Guitar, drums, piano. What else?

Bill Mumy: I play guitar, bass, drums, piano, percussion, harmonica, mandolin, banjo.

Steve Cuden: So you don’t need the resources of a quote unquote producer. You do it all yourself.

Bill Mumy: I do. That doesn’t mean that I wouldn’t rather be in a room with three other players like when we cut the first action skulls record or something. I mean, look, there’s nothing really better than looking at each other. Whether you get leakage in the mics or whatever. But seeing your bass. Somebody on bass and somebody on drums and somebody else on guitar or keyboard and going, 1, 2, 3, bam. You’re grooving together and it’s just great. I mean, obviously, I think that’s an ideal reality that is rarely afforded to me. Also, I will say this, I have a very, very, very consistent tendency to record when I get a song.

I do not like to tell it to hang out. Now, that doesn’t mean I can’t consider those recordings demos to be redone at another point in time. But most of the time, actually, vast majority of the time, I will finish a song and then that’s it. I’ll play an acoustic guitar part. I’ll sing a really rough vocal. I’ll go to the drum set. I’ll lay down a groove. I’ll sit and work out what I hope is a really cool baseline. Then I’ll start sweetening it with little keyboard pads or something. Add a couple more little guitar things. Sing it for real. Add some harmonies. Bob’s your uncle.

Steve Cuden: Do you consider yourself to be an arranger as well?

Bill Mumy: Sure. Yeah.

Steve Cuden: These skills that you have, you’ve just also developed those from being a kid forward. You didn’t go to school to become a composer.

Bill Mumy: No. Well, I took guitar lessons for four years from the age of 10 to 14, and then I’ve been in bands. There’s no better way to learn new chops or new progressions or new inversions or another instrument than being partners with somebody who can show that to you or that you just absorb it from.

Steve Cuden: So one of the things that you have in a band is you’ve got this element that you can’t control, which is the audience. When you are in the studio and you don’t have that feedback, whether from your fellow musicians or an audience at whole, at large. Is that challenging for you in some way? Do you just trust your own instincts? Or do you then need to play it for any number of people to know whether you hit something or not?

Bill Mumy: No, I pretty much trust my own instincts. No. The older I get, the less I search for confirmation from outside sources. If it feels right to me, then I’m pretty okay with it. I did study music in college for a short amount of time. I’ve had my education. Again, when we’re talking about technology, we’re living in a world where I know if something’s in tune. So if I get things right in the studio, it’s like, wait a minute. I hate to say this, but I’m not afraid or averse to using the technology of today. If I play a baseline for a four-minute song and I play it back, and I go, oh, I should have hit a C not a C sharp in that bridge. Well, I can go in.

Steve Cuden: Punch it in. Sure.

Bill Mumy: I can move that. Not even. Yes. Punch it in. Of course.

Steve Cuden: Auto tune it.

Bill Mumy: I can move that one note from C sharp to C, and that’s something you couldn’t do until 10 years ago or something. I mean, obviously I want to hear real voices and I want to hear real things, but we do have the technology to tweak things that maybe 30 years ago you would’ve maybe left because you didn’t want to mess with it. You’d say, well, okay. We can all point to great classic records by huge bands where you go, oh, there’s a goof there. There’re Beach Boys, Beatles, Doors.

Steve Cuden: All of them. Absolutely.

Bill Mumy: You can find those little things and go, oh, yeah, I wonder why they didn’t fix that. Or, wow, Paul’s voice cracked on that.

Steve Cuden: Same with the greatest movies. You can find mic drops into frame and all that kind of stuff, and all kinds of art that now they could go, and they could erase it out of that frame if they wanted to.

Bill Mumy: Exactly. Yeah. So you want to work with technology and not allow technology to control what you do. But it is pretty cool that we can do these things and we can do them in our home, you know? I have great microphones and yeah, I have really good sounding instruments. But I tell you, I’m not trying to do commercials for anybody, but you can pick up an Epiphone or a Fender Squire guitar, Fender Squire bass for a couple hundred bucks, get a decent mic and a program in your computer, and man, you can make a great record. You really can.

Steve Cuden: Yeah. It is amazing how much the technology has shifted everything. I want to be sure to cover your autobiography a little bit more before we close down the show.

Bill Mumy: Yes, please.

Steve Cuden: So tell me about your process. Did you sit down, and did you have diaries? How did you remember all this stuff?

Bill Mumy: About two years ago now, Angela Cartwright and I wrote a memoir on our years together on Lost in Space. It was published by the good folks at Next Chapter Entertainment, Next Chapter Books. It did very well. Mary McLaren, the publisher, gave me the inspiration to write my autobiography. I’ve been asked to write it many times over the years, and I had resisted it, or it had resisted me. But I do have a good memory. So here we are, I’m still choosing to stay home. A lot of people aren’t, but I’m still choosing to stay home and I’m wrestling with this thought of am I going to do this? Can I do this? How do I do this? Finally, it just hit me that the way I look at reality is not linear.

It’s not from nine in the morning till noon all the time. It’s like, oh, I’m thinking about this gig I played in 1972, and now I’m thinking about this gig I played in 2019. It goes back and forth. Your thoughts on relationships. So I said, okay, I’m going to write this and I’m going to write it in a modular non-linear way. So I was capable. It took me about 22 weeks of coming in here into my office, my studio, getting the page up here and saying, okay, what do I remember about Ozzie and Harriet. Maybe that same day I’d say, all right, let’s tell that story about locking Bob May inside the robot.

I’d be in bed at night with my wife Eileen, and she would say, what’d you write today? I’d say, oh, I wrote about this, and I wrote about that. God love her. She would say, did you tell that story? Have you written about that story where your dad stole your bike back? I went, oh, no, that’s great. I’d get up and I’d come in here. So I had this modular jumble and I started finding what I felt was the proper groove with it. I wanted to touch on the various shows that most people are familiar with. So I had those memories. But then what really helped me so much was when my mom passed away 11 years ago, we have her stuff. It’s not stuff that I look at very much, but I have several of her journals and diaries.

So I went to those. What was so great was not sharing her thoughts so much, but sharing the fact that she would write down, Billy worked at MGM on National Velvet for three days, was paid $530.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

Bill Mumy: There was all this stuff in her journals that I’m sure people will find really interesting to think, well, how much did he make. Oh, wow. He made that amount of money in 1962. That’s nothing. But here’s how much I was paid for the Twilight Zone. But she had days worked, studios worked at and other details in her journal that I certainly would not have remembered. I would’ve been able to tell you mostly correctly, not a hundred percent, but okay, I shot that at Columbia, or I shot that at Universal. But I worked at every studio in town all the time, back and forth. So I wasn’t like, oh, yeah. Was that in Culver City or was that in Studio City? It was all in her journals. So that information that’s in the book is true.

It was really fun to do it that way. I’ll be honest, I want to give kudos to a very talented, good longtime friend of mine, Sean Cassidy. Sean’s a very prolific writer and producer, and we’ve been friends since he was 14. I was in his band when he was a giant Teen Idol. I gave him an early copy of what I felt was the book. Sean gave me some wonderful notes. Again, here we go with notes. Right?

Steve Cuden: Sure.

Bill Mumy: I’ve been reading his pilots and things that he’s written for 25 years now, and I give him notes and he appreciates those. He gave me some notes on the book that were extremely helpful.

Steve Cuden: It took you 22 weeks to write the whole thing.

Bill Mumy: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: Then did you get a lot of feedback from the publisher as well?

Bill Mumy: They were very happy with the same earlier versions that I had given to Sean or something I had given to them. They were excellent editors in the sense that we spent many, many, many rounds going through typos and corrections. I haven’t found any yet. I think they really got them. Mary would say to me, are you sure you want to say that? I would live with that question. Several times the answer was no. I don’t need to say that. I can take that out. I’m better served without saying that. I mean, it’s my autobiography, but there’s some personal stories of people I worked with that I wanted their approval before I told people, well, this guy had a bad acid trip.

I wanted them to say, yeah, you can share that. Go ahead. That’s okay. So there were other things like that where a chapter here and a chapter there was sent to somebody that was very much a part of that chapter. I got their approval. Nobody said to me I wish you wouldn’t do that. I wish you wouldn’t say that. So that was really great. But there were a few times when no one said that to me, but I thought, I bet they’d be happier if I didn’t say that, and I took it out. I was just going to say, it’s not a sugarcoated book in any way.

Steve Cuden: No, it’s not sugarcoated at all. You sort of lay it out there. Some of the stories that I read were like, holy mackerel. Those are amazing stories I’ve certainly never heard before. I’ve heard a lot of show business stories. I’ve never heard those stories before. You kind of lay it on the line as to, especially in your youth. All the various, for lack of better word, trouble, you got into, as a kid. You got into various and sundry things on sets that were really kind of interesting. Just the story of you driving around, was it the Fox lot?

Bill Mumy: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: That you were underage and you’re driving around on the Fox lot every day.

Bill Mumy: Every single solitary night certainly for the whole third season anyway. I think it was the second season too. It wasn’t the first season. But yeah, the Fox lot was huge in the mid-sixties. It encompassed what is largely now known here as Century City. It was our back lot. There was a bridge. Anyway, it was five times the size that it is now. Every night when we wrapped, which was generally around 6:30. My mom had this beautiful 1962 Jaguar Mark 2, and she would toss me the keys. I would get in her beautiful jag all by myself. My mom was only five foot one, so I didn’t have to move the seat. I’d get in that Jag, and I would drive all over the 20th Century Fox lot back over the bridge to where all the shops were and wave at the guys working in the paint department or the wardrobe department. It would be about, I’m going to say, 10 minutes. It wasn’t like some great quest, but it was just a ritual, and it was a great ritual that I very much enjoyed.

Steve Cuden: You were at what age at this juncture?

Bill Mumy: 12 or 13.

Steve Cuden: Oh, 12 or 13. So you were definitely underage, and you were not on the city street. So you weren’t worried about getting arrested?

Bill Mumy: Oh, no. I was the prince of 20th Century Fox. I was very, very, very safe in terms of being in a world that was completely separate. The pocket universe from reality.

Steve Cuden: Well, I’ve been having the most exceptional conversation with Bill Mumy on StoryBeat today. We’re going to wind this thing down a little bit, and I’m just wondering, you’ve told us just this last great story, but do you have any other crazy stories or offbeat, weird, quirky or just plain funny stories that you can share?

Bill Mumy: Well yes, I do. There’s several of them. Most of them are in the book. But I’ll share what I think is a funny story. Hopefully I’ll share it in a way that your listeners will understand. We’re going back to 1962 now. We’re on the Universal Studios lot, and I am working on a Bob Hope special, and it is being broadcast live. So when you work on live TV, it’s a very different animal. It’s of course extremely rare, but it wasn’t extremely rare in the 1960s and fifties. So when you work on live TV, you rehearse it like a play several times. The directors are up in the back of the sound stage like a theater in a booth where they look down and they have little headsets that tells the cameramen. There are usually three or four different cameras in front of the set, and the directors will say, cut to camera one, cut to camera four, pull into camera three. So there’s constantly this change, and you rehearse it like a play, and then it goes live, and you shoot it, you tape it. Whatever it is. It goes live. So we’re doing this Bob Hope scene. It’s me and Bob Hope and a handful of other people and a dog. It’s a big dog, like a tramp from My Three Sons kind of dog. A big kind of sheep dog. Everyone who was watching television at home was unaware of the fact that what we were seeing as we were taping live and broadcasting this scene was during the scene unexpectedly and unprofessionally, this large dog just started doing that dog circle dance, where they start going in a circle really fast, and then they drop a huge dump in the middle of the stage. So I’m watching that, but I’m also trying not to laugh because I know that we’re working. It was the actress JP Morgan and Bob Hope, me, and this dog. I watched as this dog took a big poop while obviously up in the booth, the director’s calling, oh, no, zoom in. Camera three. So that’s just a funny little weird television, live TV anecdote that in essence, although wasn’t behind the scenes, it certainly wasn’t broadcast that way. Yet it was a pretty funny memory of mine.

Steve Cuden: To the best of your knowledge, it didn’t go out live that way. They cut around there.

Bill Mumy: No, they cut the cameras. I’m sure somebody was up in the booth. It wasn’t that much of a mystery that when you see a dog starting to do that circle thing, you know they’re going to poop. There’s really nothing they could do about it because we were out there live. So obviously they moved the camera around and so people at home didn’t see that.

Steve Cuden: Bob Hope didn’t make fun of it?

Bill Mumy: No. If he did, it was after we cut. That time I was eight.

Steve Cuden: That’s great.

Bill Mumy: That’s all my memory has maintained.

Steve Cuden: That’s a great story. Like I say and having read your book, Bill has lots of great stories in the book. Some are much more elaborate than that. But some absolutely fantastic stories are in the book. Last question for you today, Bill. This has just been so much fun for me. You’ve given us tons of advice already, but I’m wondering if you have a solid piece of advice or a tip that you like to give to people when they ask you, how do I do this? Or how do I get in the business? Or what do I do? Do you have a solid piece of advice that you like to give out?

Bill Mumy: You have to understand the difference between art and business. Because television, film, the music business, they’re all run by money maker accountant people. They’re conglomerations of big money and they’re there to make money. So if you are willing to play the game and sacrifice the time it takes then, follow your dream. But you got to try to be objective about yourself. You have to think about it. Are you really great at this? I mean, are you really, really good at it? Do you really, really want to do this? Because there’s a lot of rejection in art? Think about Vincent Van Gogh. He was really, really good at it, but it made him very miserable. So if you believe you’re really good at it, follow your muse. But if you really want to play the show business game, then be willing to compromise. You have to let rejection slide off your back. You can go into an audition. Of course, nowadays, basically auditions are sent in from a video that you do. Very few people go into studios with a casting director and sit in a room with people for most ancillary parts. You might say, oh, I nailed that. Oh, I was that guy. That was perfect. I got every word out and I believed it. It was passionate. Oh, the lighting was good. This is great. I got this one. You don’t get it right for whatever reason. You see the person six months later or six weeks later who did book that gig, and you go, what? I was so much better. Well, guess what? That’s showbiz. That’s just showbiz.

Steve Cuden: That is showbiz. It clearly wasn’t your part to have for that time, but when you get booked, it is your part and you can make hay with it, that’s for sure.

Bill Mumy: That’s right.

Steve Cuden: Bill Mumy, this has been just a fantastic hour plus on StoryBeat. I’m so grateful to have had the opportunity to chat with you today, and I can’t thank you enough.

Bill Mumy: Well, thanks Steve. It’s been fun. People can find the book Danger Will Robinson: The Full Mumy at Amazon, at Barnes and Noble, wherever people buy books online. If you want autographed copies of the book, you can get that from ncpbooks.com. It’s been a real good time today. So happy holidays and thank you.

Steve Cuden: So we’ve come to the end of today’s StoryBeat. If you liked this episode, won’t you please take a moment to give us a comment, rating, or review on whatever app or platform you are listening to. Your support helps us bring more great StoryBeat episodes to you. StoryBeat is available on all major podcast apps and platforms, including Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, iHeartRadio, Stitcher, Tune In, and many others. Until next time, I’m Steve Cuden. May all your stories be unforgettable.

This is the first time that I had listened to Story Beat Podcast. This was a well organized and entertaining interview with Bill Mumy. Interesting and enjoyable. As is Bill’s Book.

Thanks for your listening, Eric, and for your your kind and thoughtful words. I’m very glad you enjoyed the episode. Bill is a lot of fun to spend time with!

Steve

Great interview with Bill Mumy. He’s a fascinating guy!

Thank you for the thoughtful questions you asked him.

Much appreciated, Sue! So glad you enjoyed the episode! Bill is wonderful to talk to.

Steve

Thoroughly enjoyed episode 227. Thanks to Steve and Bill for the experience.

Thanks, KC. So glad you enjoyed it!

Steve

Wonderful interview

Thanks so much for your feedback, Frederick! Bill is fun to chat with!

Steve

Very Cool,fan of Bill Mumy, since I was 9 years old.

Thanks, Frederick. Bill’s really wonderful to talk to. Glad you enjoyed the show.